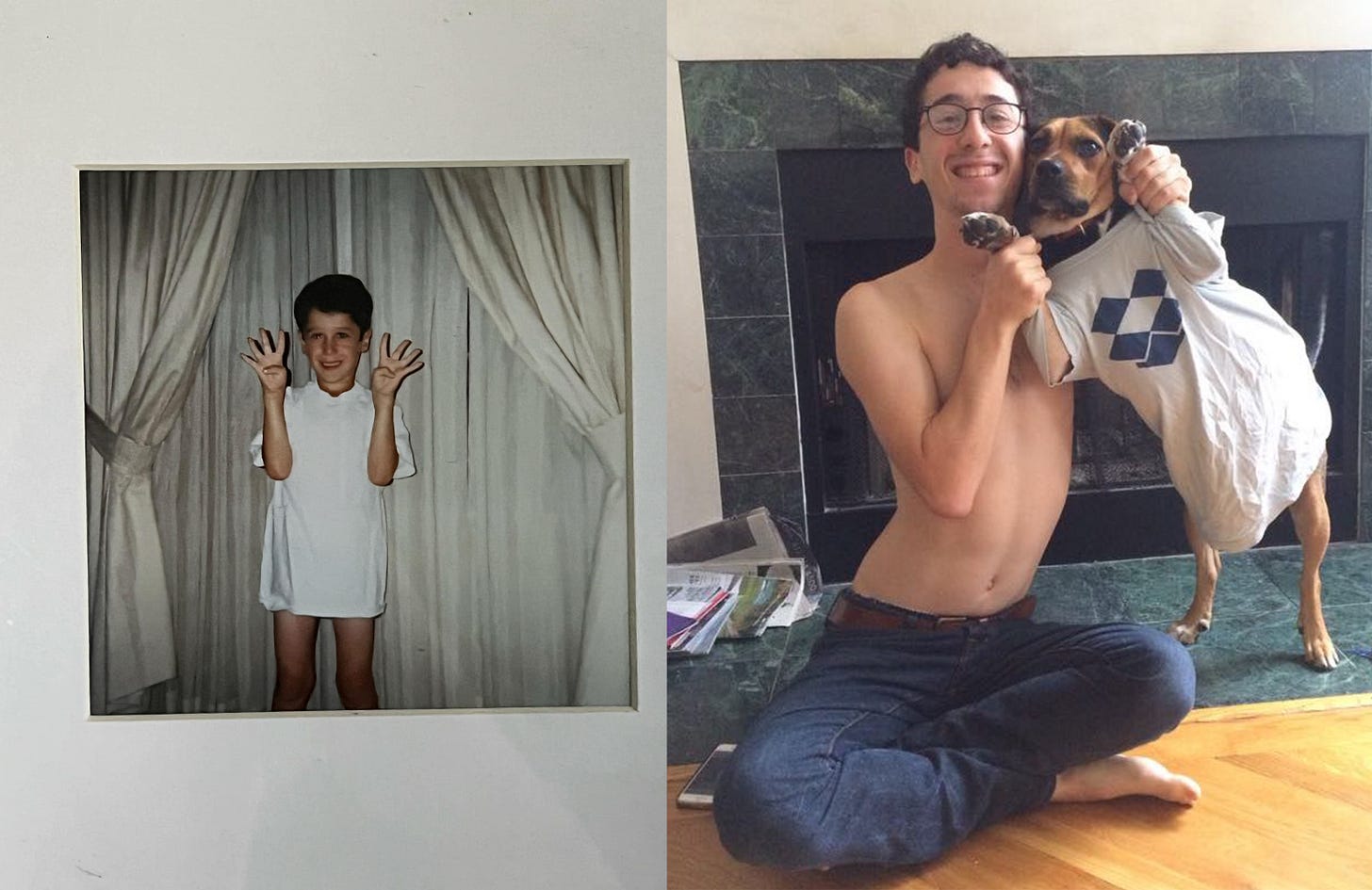

On the snow-turned-slush drive home from the animal oncologist, twenty minutes after saying our final goodbyes to our beloved old hound dog Pluto, my husband tentatively posed a question. “To break kayfabe for a moment,” he asked through tears, “are we retiring the Dog Voice?”

The Dog Voice is a little nasally, neither high nor low-pitched, to be spoken in a way bordering on singsong and liberally sprinkled with emphatics. It’s a voice that my husband and I use mostly in private1, meant to represent the way we imagine Pluto would speak if he could physically and cognitively articulate the way humans do. I suspect this is a widespread, unspoken phenomenon that occurs among many pet owners, though I don’t have the hard numbers to prove this theory. Sometimes you see bits of it through the social media profiles people sometimes build for their pets2. I assume that some subset of the millions of followers these accounts attract is indicative of the fact that Dog Voice is not unique to our household.

But Dog Voice is much more than the specific way my husband and I contort our vocal cords to “speak” as Pluto. Dog Voice includes the wide catalog of catchphrases and malapropisms that Pluto would say, if he could, that have been adopted into our private vocabulary. It encompasses a wide range of Pluto Lore that the two of us have developed over nearly a decade, a deep personification not entirely fictional in nature. It is a secret, intimate language my husband and I share, something akin to pretend play but deeply rooted in all the real-life habits, quirks, and mannerisms he readily exhibited.

I’d considered the possibility of retiring Dog Voice in those moments when sleep evades you, in the liminal space between night and morning, when the quiet solitude and relative darkness prompts you to contemplate the transience of all the tangible things that you love. But this was the first time being directly confronted with the question, and it paralyzed me. When Pluto was here, there was no need to read deeply into this strange dog/human hybrid that we frequently channel – his words mostly served as punchlines and commentary to the small funny moments that fill daily life. But now he’s not, and I’ve been forced to contemplate what to do with the ambiguous parts of my dog that exist outside the confines of his corporal body and inside my head.

It’s not as if Pluto needed personification to make him an extraordinary being – he went above and beyond in fulfilling every expectation a person could have in an animal, and it was obvious in observable, unmistakable actions. The way he’d lay his chin on those in pain (emotional, physical, spiritual, or otherwise), kind reassuring eyes from a distance for those intimidated by an animal that was once a fearsome wolf. Polite but readily evident enthusiasm he’d exhibit when he caught sight of someone he loved, traveling down the length of his spine and crescendoing in the thumps of his tail. His tendency to develop a strong preference for certain toys and proceed to leave them around the house on the windowsill he’d watch the world through, on the furniture he loved to sleep on most. Defiant huffs and puffs and whines insisting we step away from our screens and patrol the neighborhood, every day around 5 pm. Split-second hesitations in accepting offerings of food scraps to verify you wouldn’t mind sharing such a valuable resource.

No. The personification developed because the peculiarities and deeply intuitive nature of this particular dog clearly indicated a rich inner life, a thoughtfulness and a depth of feeling generally reserved for humans alone. We had inherently different perceptions and understandings of our shared surroundings, but when you are so closely tethered to something it’s difficult resist filling in the blanks with imperfect words. We saw reflections of the best parts of ourselves everyday in this beautiful animal.

My husband and I have spent countless hours discussing Pluto’s thoughts and feelings about the world that exists just outside a dog’s capacity to understand, with each trivial conversation building onto an intricate character inextricably tied to Pluto. We knew he’d have a strong preference for Pepsi over Coca-Cola – not because he’d be able to taste a difference, but because my father-in-law has an outspoken irrational brand loyalty, and Pluto’s very concrete devotion to the people he loved dictates that he’d oblige without question. His relationship with our younger and far less astute English Bulldog, Beatris, could only be described as the sort that boy protagonists of young adult novels share with their archetypical little sisters. The begrudging, exaggerated sighs he’d emit when hugged in front of polite company (only to greedily clamor into the narrow space between my husband and me each night before bed) further cemented our private canon of Pluto as perpetual tween.

Without him here, curled against my thigh the way he once was, I’m left with an invisible agent that haunts everything and has no name. In Tibetan Buddhism, there’s the concept of a tulpa, which is a sentient, autonomous thought form materialized through the intense meditation of monks and the compassionate energy of Buddhas. This is not quite the entity that remains, because it is not something entirely meta-physical; he was born from the womb of an anonymous beagle somewhere in Tenessee rather than the confines of my mind. But I think what lingers – the collective body that contains a million silly fictions based around fundamental truths, the distinctive memories of a heavy brown head on my breast – is maybe something close. He is here and not here, compelling me to cry at the sight of empty corners and uneaten containers of low-fat yogurt. Yesterday I sobbed hysterically at the tear-away Jeff Foxworthy-themed calendar my brother sent to our house as a gag gift because the daily joke referenced harming squirrels (which Pluto truly, discernably hated) and was written in a way that would appeal to the sense of juvenile Attitude-era humor we conceived for him.

Maybe you had to know him the way I knew him to fully understand.

In the doldrums of my grief, I’ve searched for answers as to why my heart feels so heavy. There doesn’t seem to be a consensus among evolutionary psychologists.

It could be a vestigial feeling, meant to teach wild beasts harsh lessons about the fragility of life. Don’t drink from the watering hole full of crocodiles. Run for high ground when you feel the rumbles of an incoming tsunami. These actions are obvious for the big-brained monkeys we’ve become, but perhaps our simpler ancestors needed that raw excruciating emotion in order to learn.

Others believe it might simply be a by-product, the cost we pay for the advantages of attaching ourselves to one another. One theory posited that grief is a show of loyalty and devotion that serves as a positive signal to potential mates intent on passing on their genes. Maybe there’s something to that, I’ve thought several times over the last few days, while clinging to my equally distraught husband.

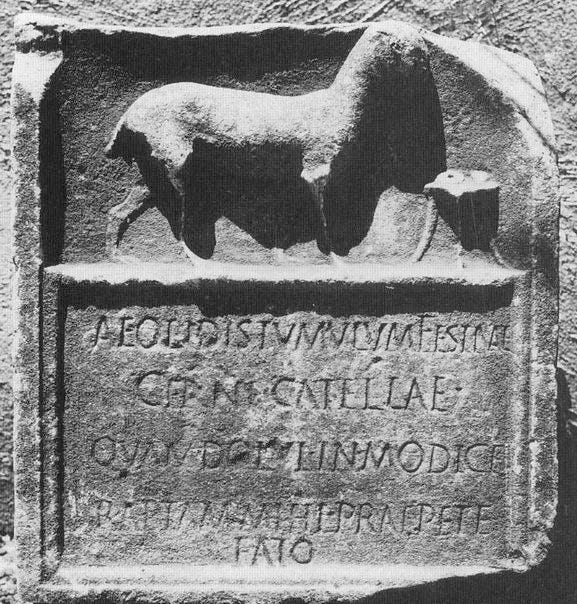

I can’t pretend to have a firm understanding of the flurry of emotions swirling through my ribcage, though I know it is natural, something that has persisted for all humanity. The Egyptians mummified their dogs in elaborate sarcophagi, then sealed them in tombs alongside their masters. Romans made epigraphs for departed pets, memorializing their sorrow in stone.

Maybe you’ve been here, too. Maybe this attachment, this pseudo-Pluto only sounds silly because it hurts sometimes to speak aloud.

I don’t know where my dog has run off to, or whether Dog Voice is canine, human, or something else entirely. But something I read recently has pushed me to embrace it wholeheartedly.

At least one study found that children with imaginary friends are more likely to exhibit certain positive attributes, such as empathy and creativity. This isn’t particularly surprising. What was surprising3 was the claim that children with imaginary friends tend to be more hopeful, and in fact hope may be the driving force that encourages children to create imaginary friends. This theory posits that such friends exist to provide support and comfort in times of hardship

And, at his core, without a doubt, that’s what Pluto was during his brief life. A comfort, a promise that good persists when all else seems bleak. He stood with us through fights and pandemics and political turmoil, totally unperturbed and often bearing a smile that expressed pure contentment. The voice that helps me laugh throughout the day, the one that my husband and I hear but can’t actually hear, is real in a way that I’m sure of but lies beyond rational explanation. And I’m thankful for it.

Judeo-Christian beliefs claim that humans were made in God’s image. Theologists have argued over the ages as to what that means. There’s one thing I feel sure of. If there’s any truth to that sentiment from Genesis, whatever divine spark that lives within us was distilled into dogs through the moment they came to be, sharing food and flame at the flanks of humans thousands of years ago. If God is to be found on this mortal plain, it simply must be by way of dog.

My dog, especially.

(Though I’m sure an embarrassing amount of strangers have overheard my ridiculous utterances in Dog Voice over the years.)

A chocolate labrador retriever named Ollie that I follow on Instagram exemplifies this well – his owner uses a text-to-speech filter on TikTok simply titled “Narrator” to bring her dog’s posh British accent to life.

To me, anyway – I don’t have children.