Everybody Hates Cocomelon

An epidemic with a stranglehold on toddlers? Or overblown pandemonium over exceptionally insufferable content?

“You can’t tell me that this isn’t well-planned-out propaganda,” states a distraught Jeremy Dale Hambly, proprietor of a social commentary YouTube channel known as TheQuartering. TheQuartering uploads approximately twenty 10-13-minute videos each week, most of which center around current events and cultural happenings curated for hyper-conservative audiences. To keep up with the breakneck pace he’s set for himself, Hambly is prone to exaggeration and occasionally needs to create stories where there aren’t any1. Even so, something is shocking in the vitriol with which Hambly speaks about a most unlikely new adversary – Cocomelon.

For the uninitiated, Cocomelon is currently the de facto kingpin of the ungovernable frontier that is children’s YouTube. The channel consists entirely of 2-4 minute videos (or longer compilations of 2-4 minute videos) centered around classic nursery rhymes and original “educational” tunes. There is little to no continuity between segments, but plotlines are straightforward and undemanding. The star of most uploads is JJ2, a computer-animated, pajama-clad baby with few defining attributes save for the fact that he is a singing baby. But what JJ lacks in-depth, he sure makes up for in singing3. Watching a series of Cocomelon segments feels a lot like being trapped inside a song that never ends.

Harmless as this all may sound, Hambly (and several other far-right, “anti-woke” commentators, for that matter) has taken great offense to a segment that recently aired on Cocomelon Lane, a Netflix-backed Cocomelon spin-off that premiered in November 2023. The segment under scrutiny features a little boy, accompanied by two men that may or may not be his parents, singing a song entitled “Just Be You”. Throughout the sing-a-long, the little boy tries on a variety of costumes while reflecting on the qualities that make him, well, him. At one point in the song, the older men point out that the little boy loves to dance. In response, the boy comes out of a dressing room dressed in a ballet tutu and tiara. In the context of the rest of the segment, there’s not anything obviously offputting about it.

Unfortunately, this 16-second clip acted as lighter fluid for the ever-burning “gays-are-indoctrinating-our-youth” bonfire. “These two gay men who purchased – an interracial gay couple, who purchased a baby – are grooming their kid to be gay? Some people might say that! I don’t know! I can’t say that for sure! But here’s a kid wearing a dress and a tiara and dancing around to entertain his interracial gay dads,” Hambly spits amid a sputtering, virulently homophobic rant. “You don’t need to consume any cartoons created in the last twenty years. There’s enough out there forever. Looney Tunes was good enough for me, and it’s good enough for kids nowadays…they are DEMANDING the Bud Light treatment!”

I don’t have much to say about the substance of Hambly’s comments because they’re ridiculous. Bypassing the bigotry, the notion of “canceling” Cocomelon is a preposterous one. Currently, there are about 170 million individual YouTube users subscribed to Cocomelon, making it the fourth-most popular channel on the platform4. It also holds the title of YouTube channel with the second most total views, at 175 billion (about 22.5 Cocomelon views per person on earth, for those keeping count). Unlike Bud Light, whose adult customers can be swayed by company politics and policies, Cocomelon is an empire designed to appease the tastes of amoral babies and toddlers ages 0-4. A visual pacifier capable of placating the emotional powderkeg that is a small child, Cocomelon isn’t going anywhere any time soon.

What is interesting about Hambly’s concern is that it is the latest to join in a growing chorus of adults who hate – and perhaps fear – the power Cocomelon wields. It is a loathing that seems to transcend race, gender, politics, and just about every other barrier we use to separate ourselves (save for age, of course). It is something deeper than the annoyance one might normally harbor toward painfully repetitive children’s programming, the kind that flourishes over many mind-numbing hours spent listening to Barney or the Teletubbies.

Time and time again, Cocomelon has been described as “cocaine for toddlers” in concerned parental anecdotes and TikTok jests alike. One word continues to reappear in ongoing conversation debating the merits and faults of Coco: addiction. And while this word is often wrapped around the protective coverage of half-jokes, as a childless woman who rarely spends extended periods with people under the age of 25, the consistent use of such a loaded word is…startling.

At this point, there’s no doubt in my mind that huge swaths of the population are concerned about what Cocomelon may be doing to kids. Shrouds of sing-song and marimba cannot sufficiently hide the fact that something about this program is so deeply disturbing that it triggers instincts in us formed long before we became human. It is danger that mothers and fathers feel compelled to shield from the eyes of their offspring, the successors of their bloodlines.

But are these nursery rhymes truly the spellbinding hex critics claim it to be? Who exactly is behind this stupid show, and why? What is it about these bug-eyed babies chanting about the virtues of eating vegetables that leaves children hooked and shakes parents to the core? And – perhaps the most important question of all – are their burgeoning fears warranted?

(If you appreciate works like this but aren’t necessarily interested in upgrading to a paid subscription, please consider buying me a coffee!)

“[My baby] does not watch Cocomelon, mostly because I’ve heard that it’s awful” - Sabine, mother of two

Finding concrete answers to these questions is more complicated a task than one might anticipate. Even the most fundamental details concerning Cocomelon’s origins and operations are murky at best.

We do know that the mastermind behind the franchise is a mysterious man named Jay Jeon. After studying film at a small art school in South Korea, he emigrated to southern California in the mid-90s. At some point, he married a children’s book illustrator (whose identity, at this time, is unknown).

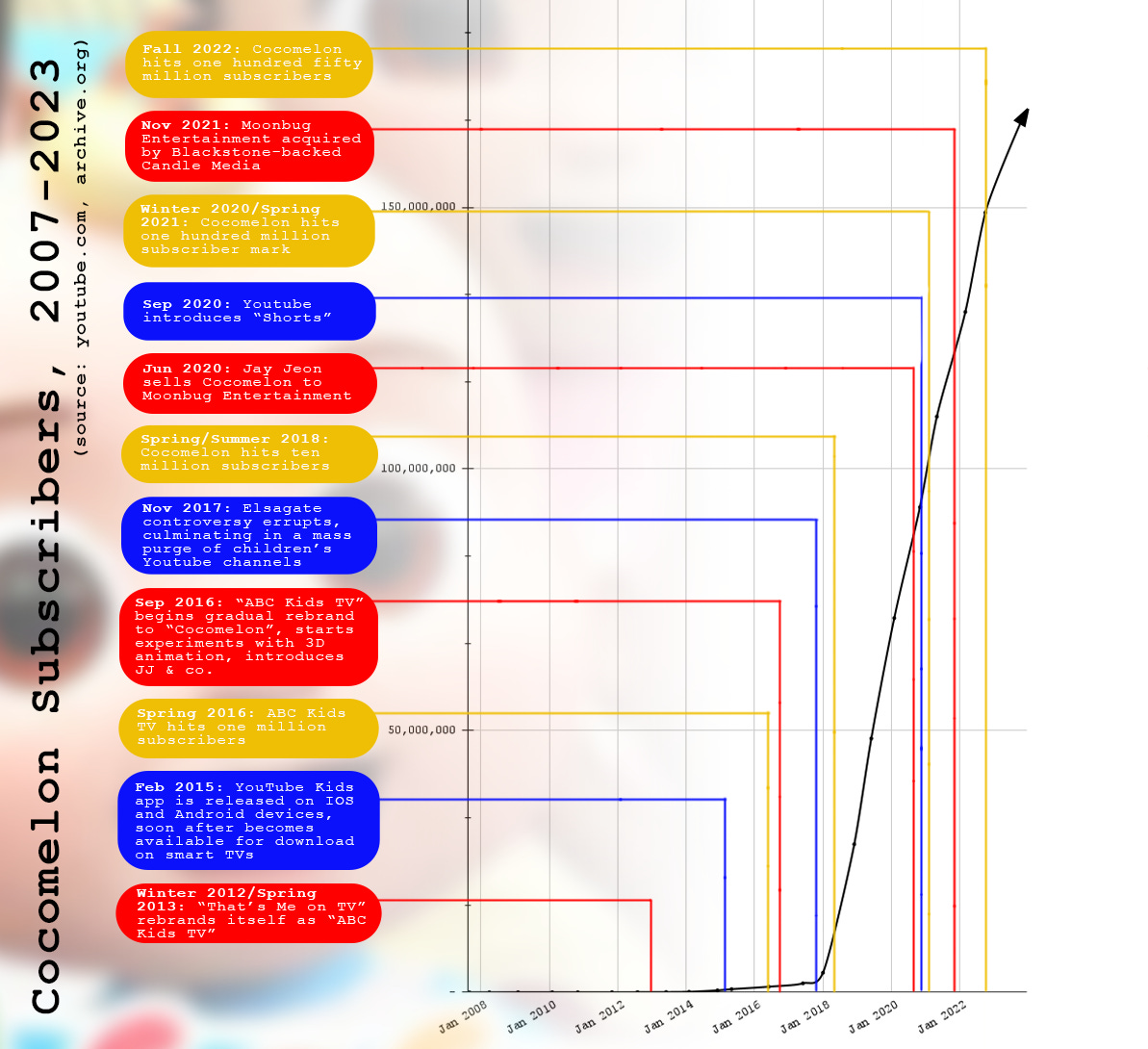

As a sort of pet project, Jeon and his wife began to make short animations around the year 2006. Initially, the videos were meant to educate and entertain their own young sons. However, after sharing their creations with “friends from church”, the couple was encouraged to upload them to an infant YouTube. And with that, a humble channel known as checkgate, was birthed. Jeon founded Treasure Studio Inc.5, the company that would eventually go on to produce Cocomelon, around the same time.

The checkgate animations hardly resemble the Cocomelon clips of today, though you can still find a few hiding in the deepest depths of Cocomelon’s video archive. They’re less polished, more painterly. Watching a checkgate-era video feels much more like listening to a storybook than a nursery rhyme. Notably, they frequently featured a super-imposed photograph of a smiling blonde-haired, hazel-eyed boy (a proto-JJ, perhaps?) interacting with the illustrations.

Between the first upload and the year 2010, checkgate rebranded as That’sMeOnTV. During that time, it seems that Jeon launched a conceptually similar business (also called That’sMeOnTV) centered around personalized children’s books and ABC DVDs, in which clients could superimpose their own children’s images into the story6. As business picked up, the channel’s viewership gradually increased.

Another rebrand came in the mid-2010s, when That’sMeOnTV became ABC Kid TV. Around this time, Jeon started making enough money on YouTube ad revenue to “quit his day job” and outsource animation and songwriting. Jeon claimed, in what appears to be his first press interview, that he could no longer remember when he began hiring contractors for his video productions. However, it’s relatively clear when examining Cocomelon’s upload history that a major stylistic change firmly took hold about ten years ago. It’s not quite the content we know today. The animation is clumsier, less whimsical, than it was in those early checkgate days. In time, flat two-dimensional characters were phased out in favor of crude 3D animations. Meanwhile, the audio abandoned storytelling in favor of the singsong chanting that’s par for the course on contemporary kids’ YouTube. With less creative energy being expended, the frequency with which videos were uploaded increased dramatically.

In 2018, the channel rebranded one final time as Cocomelon. Almost immediately, a regular cast of recurring characters, led by baby JJ (himself named after Jay Jeon), started starring in sing-a-long shorts. Around the time of the final rebrand, an upload titled “Bath Song” premiered, combining musical elements of the evergreen nursery rhyme “The Itsy Bitsy Spider” with the more recent, inexplicably popular “Baby Shark” tune. Despite some serious shortcomings in the quality of the animation7, the mashup was chosen by the gods of virality to spellbind the platform’s youngest users, garnering 6.5 billion views. At the start of 2018, Cocomelon boasted a sizable three million subscriber following. By year’s end, there were thirty-one million sets of eyes zeroed in on the channel.

This spike in popularity happened to come at the heels of Elsagate, a children’s YouTube scandal that first gained notoriety in 2017. The controversy centered around an uptick in unsettling videos running rampant on YouTube Kids, carefully designed to circumvent safety algorithms implemented to protect younger users. As Peppa Pig drinking bleach and Spiderman donning hypodermic needles slid by YouTube moderation under the guise of teaching numbers and colors, news of the nefarious practice spread. Millennial parents, all too aware of the evils that lurk online, grew frightened of what their screen-craving little ones might accidentally stumble upon if left unattended. Eventually, YouTube purged and demonetized many of the most problematic channels. However, the damage was already done and many caregivers came to wholeheartedly believe that the platform was (and still is) ineffective at filtering out nefarious content.

This misconduct paved the way for individual channels that could be trusted to reliably provide child-friendly content. During COVID lockdowns, with millions of families indefinitely confined to their homes in the wake of a worldwide pandemic, the need became even greater. And in those dark, uncertain hours, Cocomelon appeared. It has never claimed to be something revolutionary, but it does promise hours on end of safe content. It may be vapid, but it’s a tool capable of pacifying free of fetishized Elsas or murderous Mickey bootlegs. And for exhausted parents desperate to quell the wails of a child who cannot yet communicate, something as simple as that can be a godsend.

To be clear, Cocomelon is far from being the only homegrown YouTube phenomenon making millions off of the eyes of small children. Many of the platform’s most popular content creators are churning out stuff made especially for babies and toddlers, with nursery rhyme channels like Pinkfong and Super Simple Songs hitting astronomical subscriber counts in the millions. Chu Chu TV hosts computer-generated babies nearly indistinguishable from the ones starring in Cocomelon shorts.

Furthermore, one could easily make the argument that any of the parties churning out low-effort, low-cost songs and animations are less morally grey than the numerous kid’s channels that use actual flesh-and-blood child performers, wildly under-compensated and virtually unprotected by labor laws8.

Yet Cocomelon is what reigns supreme, and therefore the one at the heart of many of the most hostile criticisms orbiting kids’ YouTube.

“My kids definitely cry if you turn [Cocomelon] off […] there’s definitely a good amount [of programming] that’s super similar (and just as bad in my opinion). We have a kids Netflix account and i find myself blocking new stuff constantly for them because there’s something similar popping up all the time.” - Quinn, mother of two

“For a long time we wouldn’t let our kids watch Cocomelon, on the theory that it was too brain rotting. But eventually, they discovered other things on the various streaming [services] that are just as bad” - Chris, father of two

Though it’s difficult to say with absolute certainty what it is that drives kids crazy for Coco specifically, many concerned parties seem to suspect that the program may somehow be rewiring the brains of their little ones for the worse.

Again, on a surface level, this isn’t particularly surprising. Since the lockdowns of 2020, there’s been a significant uptick in parental concern over the potential impact of prolonged screen time on young minds. Fueling those fears is the fact that nobody yet seems to have conclusive evidence of what those repercussions might be. Recent studies have found a correlation between developmental delays and increased screen time, but not enough research has been conducted to determine whether screen time is actually the cause of those delays. Sources such as UNICEF and Boston Children’s Hospital have released ominous warnings claiming that screen time could result in attention deficits and reduced impulse control. Some researchers have gone so far as to link prolonged screen time with increased risk of ASD and ADHD, with a few fringe figures asserting that children can develop something called “virtual autism”9 from overconsumption of shows like Cocomelon.

In an interview with parents.com, professor of social and behavioral science at Walden University Dr. Rebecca G. Cowan stated that “there is no data to substantiate claims that [Cocomelon] is overstimulating due to the pace of the scenes". But in the absence of a conclusive scientific answer, parents are forced to rely partially on anecdotal accounts, where horror stories of cataclysmic Cocomelon-induced tantrums fester. Tales of “zombified” babies staring mindlessly at screens are traded on parenting forum threads free of fact-checks. And for many skeptics, watching a minute or two of any given clip seemingly lends credence to claims that might otherwise be brushed off as fearmongering.

We often take for granted just how easily our adult brains can consolidate information and filter out irrelevant detail. But let’s, for a moment, pretend that we have baby brains and explore the anatomy of an average Cocomelon clip.

In these two scenes spanning about four seconds:

The pond water is rippling in the backdrop.

Multicolored numbers in the right-hand corner are counting up to 10.

Along the bottom of the frame, lyrics switch from yellow to red, left to right.

Two fish are jumping in and out of the pond water.

A third fish jumps out of a bucket on the dock and into the pond.

The boy and the bear are startled and jerkily jump in place.

The girl toddles around in an erratic counterclockwise circle.

All the while, the “camera” is slowly panning from right to left.

For those counting, that’s eight moving elements that your baby brain is trying to simultaneously keep track of. This does not take into account the accompanying layers of audio, which not infrequently features spoken word, instruments, sound effects, and disembodied baby giggles playing in unison. It is difficult enough to break down as a person with a fully-formed frontal lobe – to say that this would be a lot for a baby to process is likely a gross understatement.

Whether this bombardment of color, sound, and movement is harmful in any way is up for debate, but what we can be sure of is that the sensory onslaught is an intentional tactic to seize attention. Every smile, every laugh or cry, every ultra-saturated high-contrast frame is engineered for engagement. A 2022 New York Times article relayed that researchers at Moonbug Entertainment (the company that distributes Cocomelon IP) collect data on details as seemingly minute as child preferences between red and yellow school buses. Toddler test subjects at the company’s London HQ are placed in rooms with two television – the first displaying prototypes of Cocomelon episodes, and the smaller second (dubbed “ the Distractatron”) showing “a continuous loop of banal, real-world scenes”. Every time an eye strays toward the Distractatron, researchers take note of the exact moment Cocomelon lost complete dominion over the toddler’s attention and subsequently make tweaks accordingly.

When this information is paired with the secretive origins of the phenomenon, it becomes easy to suspect that something sinister is afoot. In the Bloomberg interview cited earlier, Jay Jeon explicitly refused to be photographed before revealing that he liked existing in anonymity10. “We prefer to let the content we create speak for itself,” Jeon later stated in an interview with The Independent.

And, if you can work past the singsong words that encourage hand-washing and toy-sharing, what Cocomelon content says is this: it didn’t end up on top by chance. It isn’t a franchise aiming for prestige in its field, or enrichment in its target demographic. Its goal has always been one that millions of other internet denizens share – to conquer the metrics that govern YouTube and, most importantly, profit.

“Maybe it’s no different than adults that find and adore the music they listen to. But my kid would be singing Cocomelon songs anytime or place. We’d be shopping in Target and she’d be singing songs to herself […] she could also just be playing with toys or playing outside and she’d be singing their songs. Then she’d come inside and want to watch more Cocomelon.” - Rachel, mother of one

And profit it has. A 2019 report estimated that the channel raked in approximately $120 million in revenue. Cocomelon’s subscriber count has since tripled, so it’s safe to assume that that figure has significantly increased over time. In 2020, Jeon’s Treasure Studio was acquired by Moonbug Entertainment to the tune of a nine-figure payout. The following year, Blackstone-backed, Disney-exec conceived Candle Media in turn acquired Moonbug for a whopping $3 billion USD.

These numbers are entirely separate from the untold riches Cocomelon accrues through merchandise.

Though you may have made it this far blissfully unaware of Cocomelon, you’ll now be unable to unsee that you’ve been surrounding you all along. JJ’s unblinking eyes will stare at you from the spouts of single-serving apple juice and the polyester fabrics of pajama sets. The unfortunate watermelon/television hybrid being that serves as the channel’s mascot, ever-grinning, will start to show up in places you’d never expect.

Cocomelon’s all-encompassing grip does not relent the moment you log off of your computer or exit your grocery/retail store of choice. You’ll begin to notice it on the iPads of children in restaurants, in transit. Anywhere and everywhere, really.

On the Las Vegas strip, you’ll find people in bootleg baby costumes11 willing to pose for pictures in exchange for cash. In Times Square, you might catch a Cocomelon character crawling along one of the many digital billboards.

Perhaps this is where the evil – or whatever it is that is so unsettling – lies. There’s comfort in the notion that ousting the right person, or turning your device off entirely, will make Cocomelon go away. But we’re already surrounded.

Will Cocomelon make your kids gay? Probably not. Is it a catalyst capable of triggering autism in your baby? I highly doubt it.

It is, however, an entity that exists to absorb, indifferent as to whether it is a positive or negative influence so long as it makes money. Cocomelon was designed to game the human mind, and it has thoroughly succeeded in doing so. It represents something unkillable that we don’t yet understand. Even if Cocomelon were to disappear from every streaming platform, every box of pull-ups, every child’s mind, the essence of what Cocomelon is would still survive in the perpetual sea of Coco clones that are being uploaded to the internet at this very moment.

And that, like it or not, is something that we’ll all have to live with.

A perfect example comes in the form of a January 3rd upload, titled “Disney Just DESTROYED Star Wars FOREVER With INSANE Feminist Activist Given FULL Control Over Movie”. Despite the alarming title peppered with caps-locked buzzwords, the video primarily criticizes Canadian-Pakistani filmmaker Sharmeen Obaid-Chinoy (slated to direct an untitled 2026 Star Wars installment) for uttering the phrase “I like to make men uncomfortable” during a Women in the World summit eight years ago.

Sometimes videos revolve around JJ’s family members, friends, or even play-pretend animals but even when JJ himself is not on the screen the fact remains that JJ is the undisputed center of the Cocomelon universe and we are privy only to the goings-on of the people in JJ’s immediate inner circle.

If you want to be technical about it, JJ is never shown actually singing in Cocomelon videos – instead, a voiceover singing in what is implied to be JJ’s voice is overlayed over the JJ footage. All that actually comes out of JJ’s mouth are the incongruous giggles and coos of a baby. It’s somewhat unnerving, and once you notice it, it’s very difficult to unsee. For reasons unknown, JJ and co. do use their voices to talk and sing in the new Cocomelon Lane series.

A case could be made that Cocomelon is the third most-subscribed channel. One of the three channels with more subscribers is YouTube Movies, a product tied directly to the platform itself. In this case, only MrBeast and T-Series (a massive record label and film producer that holds a share in about 35% of India’s music market) boast more subscribers as of January 2024.

There is little to no public information available concerning Treasure Studio Inc., just in case you were wondering.

Content purporting to be from the That’sMeOnTV ABC DVD that Jeon and Treasure Studio Inc. released is currently archived on YouTube. It appears that the DVD simply aggregated all of the ABC uploads available on the original checkgate YouTube account and switched out the photograph of the little blonde boy with clientele-provided images.

Solid, opaque bath bubbles fill the tub in a clear attempt to mask the animator’s inability to replicate the appearance of liquid matter.

There is one photograph that’s often attached to Cocomelon’s Jay Jeon appears to fit the few physical characteristics we know about Jeon. However, I’m inclined to believe that the image claiming to portray the Cocomelon founder depicts an unrelated Jay Jeon connected to the South Korean film industry. While these Jay Jeons may be the same entity due to Coco Jeon’s Korean film school background, the latter’s former role as director of the Busan International Film Festival is not congruent with the anonymity our Jay Jeon appears to closely guard. This uncertainty and contradictory information just goes to show how little information is readily available concerning one of the single most powerful individuals in the children’s entertainment industry.

Romanian clinical psychologist Dr Marius Zamfir coined the term “virtual autism” in 2017 to describe the spontaneous manifestation of “autism-like” symptoms linked to screen time. Over the past several years, concern over the supposed condition has slowly spread worldwide via platforms like Twitter.

Virtual autism is not a medical diagnosis and completely ignores the fact that years of reliable research suggest that autism is strongly linked to genetic factors and prenatal/perinatal environment. In contrast, evidence linking postnatal factors to autism is almost entirely anecdotal.

In the United States, anyway. In August 2023, Illinois became the first state to ensure some form of financial compensation for “kidfluencers”, though the new laws will not go into effect until the summer 2024. Senator Steve Padilla introduced similar legislation in California last month. Some countries, such as France, have attempted to enact laws to protect kids performing on YouTube, but thus far said protections have remained limited.

I’m not sure where else to fit this in, but I’d be remiss if I didn’t share that after conducting this research stuff like this has begun to infiltrate my feeds. You’re welcome.

We don’t do Cocomelon because I’m trying to raise snobbish weirdos like myself, so this was spectacular to read, a comprehensive introduction! Love your posts!!!

Such a good article! So well researched and was waiting to get to this and see what you thought:

"Whether this bombardment of color, sound, and movement is harmful in any way is up for debate, but what we can be sure of is that the sensory onslaught is an intentional tactic to seize attention. Every smile, every laugh or cry, every ultra-saturated high-contrast frame is engineered for engagement. A 2022 New York Times article relayed that researchers at Moonbug Entertainment (the company that distributes Cocomelon IP) collect data on details as seemingly minute as child preferences between red and yellow school buses. Toddler test subjects at the company’s London HQ are placed in rooms with two television – the first displaying prototypes of Cocomelon episodes, and the smaller second (dubbed “ the Distractatron”) showing “a continuous loop of banal, real-world scenes”. Every time an eye strays toward the Distractatron, researchers take note of the exact moment Cocomelon lost complete dominion over the toddler’s attention and subsequently make tweaks accordingly."

We've steered clear of cocomelon (or anything American for that matter, sorry!) since day one, cocomelon is everything I think is awful about today's kids tv. We mostly have let our daughter watch Studio Ghibli and programmes like the Clangers, and the original Winnie the Pooh—all much slower pace, sweet storylines which are fantastical and fun, and not trying to grab her attention a million times in a minute to drive her to distraction. I try not to preach about this—but screens and what we let children watch is definitely something I care and think a lot about. Sure they can choose later, but we have microscopic control over so many key areas of their lives as a carer (what they eat, where they go, everything), so why not make sure what they consume digitally is also just as nourishing for their brains. Cocomelon feels to me like the equivalent of giving her a litre of coke to drink then wondering why she has a catastrophic meltdown half an hour later when her brain is popping off with sugar. As a parent you have to make hard choices which can often make you super unpopular with your child (and other parents) but this is one, so far, I haven't regretted for a second.