My Instagram, My Brother, and My Roundabout Brain

On neurodivergence and algorithms that speak the things you can’t say

Recently, my Instagram account learned that I have Autism Spectrum Disorder.

I’m unsure what initially tipped the platform off. Perhaps I lingered a bit too long on someone else’s post. Maybe it was just a natural realization, stemming from the information we’ve quietly fed one another over many years. All I know is that lately, alongside the usual short video clips of English Bulldogs riding skateboards and DIY art-making techniques, I’ve been not-so-gently “suggested” content centered around the autistic experience.

Like the disorder itself, the media comes in a wide spectrum. Sometimes, it is in the form of comedienne Laura Beitz performing a bit, joking that she’s been diagnosed by “everybody that’s ever known [her]”. Other times, it’s a mother whose words read more like diary entries than social media posts, relaying the trials and tribulations faced by her nonverbal autistic son. I have been pushed links to one New York Magazine think piece penned by Mary H.K. Choi on coming to terms with late-diagnosed autism no less than two dozen times within the last month.

Often, I get deeply, intensely entrenched in circuitous thought1. Sometimes, in making art or writing an essay, this trait works to my advantage. But when I get trapped inside a particularly insidious anxious thought, it’s debilitating, just short of paralyzing. When I tried to explain this internal struggle to a new doctor two and a half years ago, they suggested that I might be struggling with undiagnosed ADHD. After taking a series of tests through a second, specialized psychiatrist, the results revealed that definitively wasn’t the case. Instead, I walked out of the office with a document claiming a diagnosis of “Autism Spectrum Disorder, Mild2”.

For a long while, I felt doubt concerning the conclusion the doctor had come to3. To be told you’ve spent a lifetime unwittingly trying to maneuver around a disability you didn’t know you had is wild, world-changing. For a time, it seemed more rational to believe that I overthought and incorrectly answered some of the self-assessment questionnaires used to determine the quantifiable data.

Mostly, the shock stemmed from thinking that I already had an intimate understanding – as much as one can have, anyway – of what autism is and isn’t. Years before my memory begins, my oldest brother, Chris, was diagnosed with autism. It is hardly a coincidence that I have it, too – the current scientific consensus is that siblings of autistic children have about a 1 in 5 chance of being autistic themselves. However, his autism is the sort that isn’t talked about in think pieces or social media posts, because it is complicated by comorbidities and painful in its lack of satisfying resolution.

Chris does not speak, write, or type out his thoughts. Elbow and radial dysplasias that, as far as I know, have no specific name, greatly impede his physical ability to utilize sign language (save for a few simpler gestures such as “thank you”). He sometimes points or nods to indicate a need or want, though only on his terms. The subtlest of queues in body language – the kind of queues that I really, really struggle to interpret – sometimes hint at his general mood. The reasons why he might be feeling a certain way are much more difficult, if not impossible, to pinpoint. This profound inability to communicate makes it difficult to determine whether his frequent lack of discernable response is due to a lack of understanding or simple apathy.

Growing up alongside someone like Chris has benefits4. I am often praised for my patience. The same praise can be applied to all of the members of my immediate family, because it’s a trait that develops out of necessity. I am capable of putting others before myself, of tolerance and compassion for those who experience life differently. I have learned to accept and value the eccentricities of others, to forgive missteps and irritants, and to find gratitude in things as simple as your voice – all attributes that may not have manifested without Chris’ presence. I am thankful that he’s taught me these lessons, and I like to think he has helped me become a better person than I might otherwise be.

But large swaths of it were (still are) painful. Maybe “complicated” is a better, more encompassing word. I’m happy to provide the extra support he needs in whatever ways I can. I’ve never wished that someone else might take his place. But I wrestle with the fact that everything is an educated guess, because I hate guessing.

I like to be sure, to have feelings and needs and boundaries and expectations communicated as clearly as possible. This is simply not an option in my relationship with Chris. If there was a way to trade all of the good to gift him a voice, I’d do so without hesitation.

It is hard to know my brother, even though he is my brother. I have to infer who he might be, what he might want, and how he might feel through glimmers and hints. Maintaining a relationship at all, now that we live 1000 miles apart, is difficult. Any phone call I place is guaranteed to be one-sided. A day will likely come when I will be the one (partially) responsible for making difficult decisions that will directly impact his quality of life, and I fear that I will fuck up. I love my brother, but I will likely never know with certainty whether he loves me back.

It is the great heartbreak of my life, a heartbreak I was born into that few can fully comprehend.

So to be classified under the very label that had served as a scapegoat for years of anger, that functioned as the heart of so many of my greatest fears, has been…strange. It’s much easier to ignore than make sense of, and that’s largely what I’ve done. Up until now.

Now, my Instagram account is insistent on confronting me head-on about it.

This shifted algorithm has been showing a lot of women that look a hell of a lot like me. They look young, seemingly normal, even well put together in the way social media influencers often are. But they poke at secrets I’ve never spoken out loud, writing them out in image captions and performing them in front of smartphone cameras rigged to tripods and ring lights.

Some touch on small secrets. Not secrets, even, just strange habits and sensations that I try not to bring attention to. They straddle the line between normal and abnormal, things that may or may not be indicative of anything at all. I don’t talk about the fact that the textures of certain types of styrofoam and those non-slip poolside draining mats and sidewalk chalk have always been so jarring and unpleasant that it always takes a second or two to regroup and stop all the atoms in my body from screeching in displeasure. When the anxious energy that lives deep in my belly starts to boil, it shoots through my arms and I rapidly tap my thumb against the pad of each finger to calm down: pinky, ring, middle, pointer, repeat, repeat, repeat. I always perform this inexplicable, repetitive release at the level of my hip, where eyes don’t often wander. Every now and then, my emotions feel like too much to bear, in a way that can’t be mitigated by weird little soothing rituals. I’ve gotten better at containing them as I age, but I can still remember the days when my mother would flip through books with titles like The Highly Sensitive Child. The fact that I couldn’t get a handle on my insides and she needed to read such things on my behalf filled me with shame, which is probably evidence in itself that I was, in fact, a highly sensitive child5.

Other truths feel more invasive, dredging up lifelong insecurities I’d attributed to some catastrophic intrinsic shortcoming rather than a signifier of autism. I’m being informed that my inability to organically start a conversation, to carry on with idle chit-chat, to look others in the eye are symptoms of something systemic within myself, completely commonplace within the context of my alleged neurological condition. Suddenly, my Instagram somehow seems to know how much effort I put into ensuring that my facial expressions and body language match what’s socially expected of me, and how hard I try to maintain the rhythm of conversation. It grasps how much an uninvited hug can silently make my innards squirm, how fucking uncomfortable the touch of another person can be. The fact that I never voice these particular discomforts, for fear of being branded a frigid bitch, doesn’t matter.

These posts – the ones I see myself in for better or worse, the kinds that keep coming up – are deeply conflicting. I don’t mean this in a wholly personal, deeply-internalized sort of way. Entire online communities are torn to shreds concerning the rise of autistic influencers and content creators inherent with the rise of autism diagnoses as a while.

On one hand, there’s reassurance in the willingness of some to share in their experiences candidly. They offer explanations to individuals who have spent entire lifetimes feeling foreign in their own skin, scriptless in a world where everyone else has their parts memorized. In comment sections, you’ll find dozens of anonymous accounts expressing deep appreciation, sharing relevant anecdotal experiences, and confessing that they feel recognized for the first time in their lives. Particularly as a woman who slipped through the psychiatric cracks, there is validation and understanding in the ~80% of autistic women who evade diagnosis until adulthood. Machine learning, having achieved something akin to mind reading, has made it so that such reassurances can make their way to those who may not yet have the keywords necessary to unlock the answers to themselves.

Conversely, the nature of existing and thriving in a like-and-subscribe-driven economy necessitates a level of performance that flirts with inauthenticity. Large swaths of neurotypical and neurodivergent viewers alike openly wonder if the line between awareness and romanticization is being skirted by content creators reducing ASD with a mere quirk, a removable accessory self-diagnosed Manic Pixie Dream Girs far and wide adopt at will in hopes of adding depth to their identity and aesthetic6. The undercurrent of sexism often prevalent in cries of clout chasers “faking it” isn’t lost on me. That said, I understand the instinct to cringe when cutesy terms like “neurospicy”7 are applied to something that can range from tremendously isolating at to entirely debilitating. Some complain that dogged efforts to accentuate the positives of something too complex to fit into the binary of “blessing” or “curse” have erased the experience of those whose struggles are more profound.

And on this front, such critics aren’t entirely wrong. Autism doesn’t often manifest as some rose-filtered, Instagram-friendly Zooey Deschanel fantasy. As much as I find comfort in those willing to share what autism sometimes looks like, it’s impossible not to think of my brother. There is a distinct lack of the painful parts that are so familiar. Instagram cuts out the violent flailing of arms that hit hard in moments of unbridled frustration, impossible to articulate. There are no mentions of the bloodied vomit stains on the carpet that serve as a reminder of an ailment that went undescribed and undiagnosed for years because you couldn’t speak about the hurt. Almost always, the ugly, overwhelmed tears are omitted in favor of something more palatable8.

Perhaps I’m overanalyzing the significance of the fleeting things that populate my feeds for brief moments, specifically targeted as they may be. It wouldn’t be the first time. Ultimately they’re just images, being pushed to me on an image-sharing platform.

Then again, the moments I’ve felt most connected to my brother – who I cannot help but think of with each passing suggestion – are the moments we’ve spent breaking down the details of images. The image is the most comprehensive language that we share, the one that touches closest to conversation.

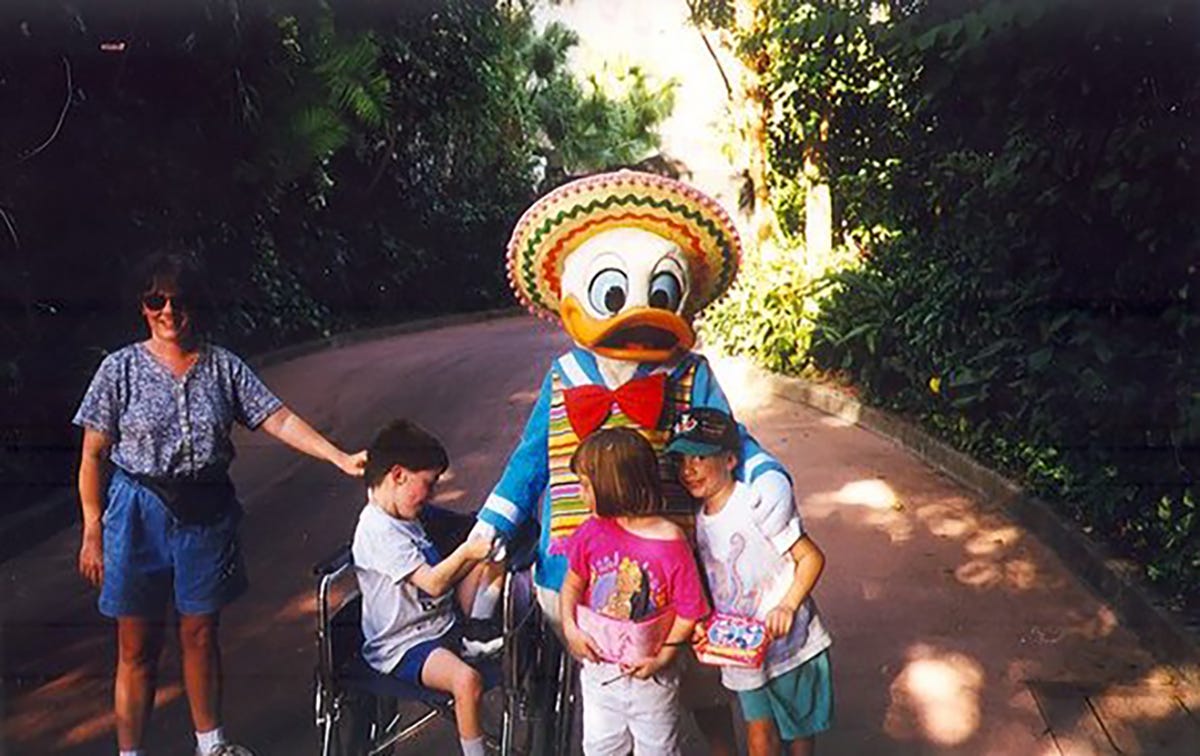

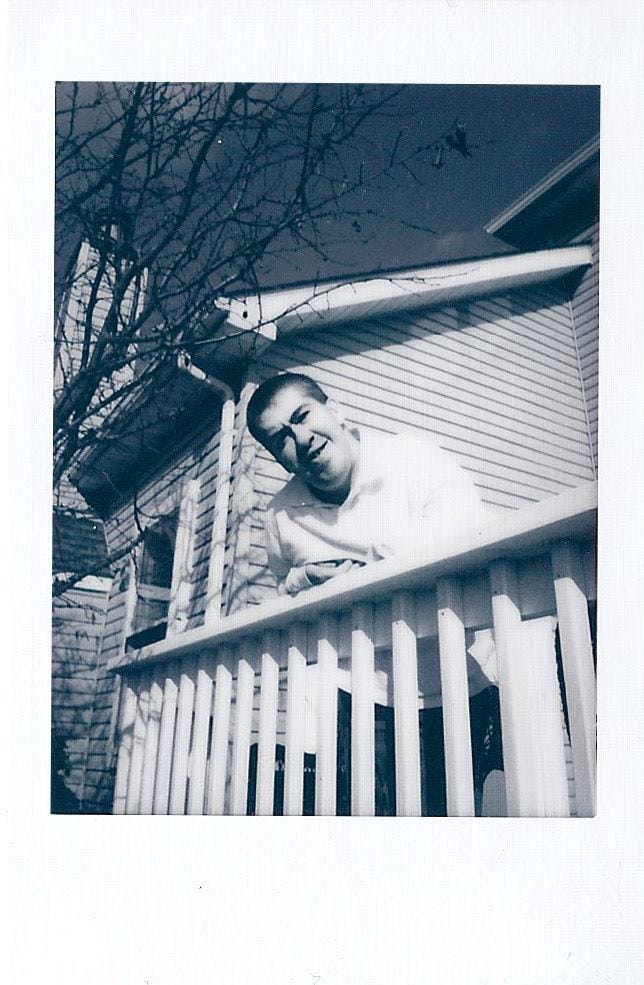

It started years ago, with the photo albums he’d dig up from the depths of my parent’s closet9. Many of the prints come from times I largely do not remember. But when he feels like flipping through the pages, he points intently to things crystallized on each glossy sheet. Younger versions of ourselves, deceased relatives, toys long gone from our lives, places we’ve visited. I am not sure of the specifics that determine why he points. But it is something real, unmistakable. Not an invented projection, not a misinterpretation of action but a concrete expression. For just a moment, there are no doubts that we’re sharing the same idea. Yes, I recall the sandbox shaped like a turtle, and the little red car you had to use your feet to propel forward10. Yes, I remember the houses momentarily made homes on vacations spent beachside, with names like ‘Serenity Now’ and ‘The Laughing Gull’. No, I haven’t forgotten our grandfather, who died just shy of my ninth birthday.

As the years have passed, I see less of the photo albums when I get the chance to visit. Instead, I often find my brother on his iPad, browsing YouTube. He lets the site guide his journey, allowing the platform to play whatever it pleases from its endless arsenal of content. He quickly swipes past many recommendations after a second or two of observation, lingering only on those that pique his interest. In this way, YouTube’s algorithm has developed a loose understanding of his likes and dislikes, no words or queries necessary.

Some of what I catch floating by his screen is relatively predictable. For reasons I’ll never know, he’s always been fascinated with pipes, faucets, and plumbing. So, strange and absurd as it might seem, I’m not exactly surprised when I find him hunched over the kitchen counter watching toilet flush compilations.

Other favorites are a bit more puzzling, playing on repeat for reasons that aren’t immediately obvious. Sometimes, I find myself ripping apart each second in an attempt to understand what’s happening in his head.

When I saw him last, this past July, variations of the following 20-second, Alvin and the Chipmunks-esque song got a lot of playtime:

On a surface level, there’s really not much to it – a cute cat, a catchy little tune, some commentary on anthropomorphism in pets. Occasionally, I’d catch a small smile break across his face. But why? Is there humor in that cloying, high-pitched crooning? Could it be that he is fond of cats, despite the outward indifference he generally displays toward animals? Maybe he recognizes something absurd in the way my mother dotes on the family dog11, usually situated no further than a room or two away. Possibly, it’s got something to do with the play on The Chordette’s musical “dum dum dum” pseudowords and the insult “dumb”.

It could be all or none of those things that catch his eye and make him laugh. But there’s something in those 20 seconds, somewhere. When a person you love is deeply inward, entirely unable to provide answers to any of your clarifying questions, it feels meaningful. You have to try to find meaning in whatever unlikely place it might be found.

All the years of probing and prodding and dissecting every little thing an image has to offer guided me toward the study of photography as a college student. Even now, I generally have some sort of camera on hand – usually a Polaroid, because I’ll otherwise take slight variations of the same photograph over and over and over again, never satisfied because the image on the LCD never matches exactly what’s in my head, doesn’t communicate the exact concept that I want to convey. A traditional career in the field was crushed for me the moment I realized that getting ahead often means pushing your way through crowds or placating unhappy clients or accepting a touch on the small of your back from some old pervert with influence. Navigating things I’m not equipped to handle, and maybe never will be.

But I never wanted to photograph for others, anyway. What I wanted was to understand all of what lies in the stream of images we’re compelled to produce and consume.

It’s what I still want. It’s all that I’ve ever wanted.

Which brings me back to Instagram.

I’m not sure how Instagram came to know the most private parts of me, despite being just one in a sea of 2.5 billion users. But it’s figured me out. It’s discovered the parts I largely haven’t shared with friends or family or colleagues for fear of being othered or infantalized or pitied.

Logically, I realize that these “revelations” boil down to a series of complex computations based on my every minute interaction. But at times, it feels like something closer to God12, all-seeing, trying to reach out in a language more nuanced than what words alone can accomplish. Does it know that the secrets to the universe, to my brother, to my own contorted mind may lie in the way the light falls, how colors bleed, where pixels arrange themselves on screens? Does it realize that no matter what I do, I can’t look away and stop my search, regardless of how mundane and silly it sometimes presents?

It’s easy to be scared, when something you don’t quite understand scrapes at your core. Maybe I should feel fearful that every science fiction dystopian nightmare of computers that know too much seems to be coming true before my eyes.

But I don’t feel scared.

Sometimes, I think, there’s good in digging at what’s hard to grapple. I suspect that it’s integral in understanding the parts of yourself and everything around you that matter the most.

And if each strike comes in the form of calculated suggestions, I’ll gladly take the blows.

If you enjoyed this essay and want to say thanks, please consider buying me a coffee 😎

Now, I realize that there’s a name for this inability to break out of certain mental loops – perseveration. It’s a pretty common trait among autistic people, but for years I struggled to articulate this particular thought trap to others properly.

“Mild” is the doctor’s word, not my own. The DSM-5 categorizes ASD into three levels based on support needs – as someone capable of “passing” as “normal” and living independently, I would fall into the “ASD Level 1” bin. But saying that I have “Level One Autism” sounds ridiculous, so I suppose “mild” will have to do.

(I really shouldn’t have been that surprised. The doctor’s writeup claims that I went into excrutiating detail discussing the manifestation of post-9/11 American ideology in the fourth season of Survivor, which aired when I was nine years old.)

Benefits as a witness and caretaker, anyway. Unfortunately, I can’t speak on behalf of my brother, and I can’t tell you how he feels about having autism, therefore I can only offer the selfish lens of my own experience.

For years, autistic individuals were uniformly characterized as lacking in empathy. While this may be the case for some, recent findings suggest that many others experience hyper-empathy. Interestingly, there seems to be a fair amount of recent debate regarding whether or not autism is synonymous with being a Highly Sensitive Person (HSP) (as defined in psychotherapist Dr. Elaine Aron’s 1991 parenting guidebook, The Highly Sensitive Child). There seems to be no clear consensus on the matter, with some insisting that they are separate attributes and others arguing that there are virtually no differences between the two.

Obviously, this discourse was non-existent 15-20 years ago when my mom was reading The Highly Sensitive Child.

A few examples to illustrate what I mean:

TikTok user “ljtruth” posted a viral 92-second rant last year claiming that “people wanna be neurodivergent because the only other alternative to that is being neurotypical, and nobody wants to be typical…everyone still wants to view themselves as special, and the easiest way to do that is to claim you have some sort of intrinsic attribute that makes you different”.

There are a plethora of posts across autistic subreddits that read like this post, in which a user articulates her frustration toward women who make autism look like a “fun, quirky personality trait” and (allegedly) deny that ASD is a disability.

Youtuber “I’m Autistic, Now What?” describes her personal experience with individuals skeptical of her autism as follows: “I would say that 80%, at least 80%, of the time I share my diagnosis with people in real life – even people who can see my medical record, right there in front of them…I have a negative experience, and there is a huge air of ‘I don’t believe you’. It doesn’t make me feel special at all.”

In fairness, I first heard the term “neurospicy” on an episode of 90 Day Fiance: The Other Way, not my Instagram feed. Statler, a 33-year-old recently-diagnosed autistic cast member, uses the term to describe herself as she willfully pisses in her own bathtub. Cringe is not a strong enough word for the physical reaction that overcame me, fueled by the fear that someone out there might now equate autism with bathtub pissing. I can only imagine that she picked this term up the term “neurospicy” from Instagram or Twitter or TikTok accounts not entirely unlike the ones that get pushed on me.

It’s a horrible Catch-22 – those most impeded by their autism are frequently the ones most reliant on loved ones to advocate on their behalf. But, try as we might, we’re imperfect conduits. How do you share the experiences of someone largely unable to communicate without letting your own separate biases and interpretations overshadow the person you’re trying to speak for in the first place?

This neverending wrestling match is perhaps most evident in the online autistic community’s adoption of the #actuallyautistic hashtag more than a decade ago. Ironically, autistic individuals seeking firsthand accounts from kindred spirits have long found themselves unwelcome on more generalized hashtags. For instance, #autism is largely populated by (generally neurotypical) loved ones relaying indirect experiences and awareness organizations (such as Autism Speaks) that have historically demonized autism (as opposed to offering more concrete support).

It’s a messy issue without a realistic solution. As a result, unmediated accounts of the ugly parts to overcome are harder to find and largely undiscussed, real as those ugly parts may be.

Actually, it started even earlier than that. For a while, he used PECS (which stands for Picture Exchange Communication System) to communicate some basic thoughts. However, he only used PECS on his own terms, when prompted, primarily to communicate surface-level ideas. For instance, when asked the question, “What do you want for dinner?” he might offer “hot dog” or “hamburger”. That said, he might also answer with something nonsensical “eyeball” or “umbrella” if he wasn’t in the mood to entertain your question.

Not dissing my mother here– I dote on my dogs just as much, if not more so. I’m confident that I understand dogs more than people, so it’s hard not to.

Isn’t he famous for working in mysterious ways??

I’ve never met someone else who does the progressive finger tapping thing! Hello tappy friend! I think for me it’s not so much of a soothing thing as a return from space and back to focus thing. Although maybe that’s just another form of soothing? Brb gotta reevaluate my entire life again.