Sugarcoating the Dangers of Football

Exploring the history of how – and why – we've sold contact sports to kids for generations, obvious risks be damned

A special thanks to my older brother and all-around sports pundit of choice, Kevin Boilard, who was an immense help as I wrote this essay. You can follow his coverage of the Premier Lacrosse League (and more!) on Twitter.

Every Wednesday at 7 pm EST, Nickelodeon drops their latest installment of NFL Slimetime, a candy-coated fever dream of a football highlight reel. Unlike the majority of Nickelodeon’s current programming, this new series is not a spinoff or reboot of a tried-and-true franchise like Rugrats or The Smurfs. Instead, it is a half-hour solely dedicated to the goings-on of the National Football League. Each week, the best passes, catches, and touchdowns are spliced between sound bites of players postulating whether Spongebob Squarepants or Patrick Star would make a better wide receiver. NFL-receiver-turned-TV-host Nate Burleson and 13-year-old Dylan Glimer (aka “Young Dylan”) speak only in exclamations. Attached to almost every movement is an animated embellishment. For approximately 21 minutes, the playing field transforms into a realm that straddles reality and cartoon absurdity.

But on Slimetime’s October 5th broadcast, something was missing – any mention of Miami Dolphins QB Tua Tagovailoa.

In most cases, the absence of a single player might not be especially noteworthy. After all, the folks at NFL Slimetime have roughly 48 hours of new footage to go through each week, and there are a whopping 1,696 players that make up the NFL’s active rosters. But Tua isn’t just a mere quarterback – he’s a personality.

Prior to October 5th, Tua made appearances on all three episodes of NFL Slimetime covering the 2022 season. On week 1, he was superimposed into Bikini Bottom and delivered a few eager “I’m Ready!”s between segments. Tua was then selected as the recipient of Week 2’s NVP (Nickelodeon’s Valuable Player, for the uninitiated) award, rounding off an episode filled with footage of Tagovailoa sending the ball soaring past the Baltimore Ravens. Week 3’s episode showed footage of Tua showered in slime by his teammates as he’s handed a bright orange, blimp-shaped trophy. Burleson and Young Dylan specifically mention the Dolphin’s upcoming game, slated to take place September 29th, as a must-watch event.

For anyone vaguely familiar with the goings-on of the NFL, Tua’s omnipresence should come as no surprise. Though he was frequently injured, Tagovailoa enjoyed an impressive college football career – so much so that he was chosen to be the face of ESPN’s 2020 NFL Draft commercial over Heisman trophy winner Joe Burrow. Tua has also appeared in commercials for Adidas and Muscle Milk, as both companies were eager to endorse him before he ever set foot on a professional football field.

Perhaps more impressive than Tua’s raw talent is his charismatic disposition. He is a man that you need to make a concerted effort to dislike. Infectious is the best word to describe his smile, and he has a penchant for playing the ukulele. There are even videos of him happily plucking away at his instrument of choice in a hospital bed post-hip surgery following a “high-impact injury more likely from a bad car crash than something you see in football players”.

From a marketing perspective, Tagolaivoa’s impressive skills on the field and sheer magnetism outside of the game made him a perfect representative for the league.

Until Week 4 came, when that “must-watch” game reared its ugly head.

Halfway through the second quarter of the Thursday night football game, Cincinnati Bengals defensive tackle Josh Tupou made his first career sack and slammed Tua head-first into the unforgiving ground. “Uhhhhhh….uh oh,” fifty-year veteran commentator Al Michaels fumbled in front of an audience of 11 million. It was evident at this point that something was very, very wrong. Tagolaivoa, still lying flat on his back, locked his arms at a 90-degree angle as his fingers contorted into unnatural positions.

Some viewers immediately recognized that the star quarterback was displaying what’s known as decorticate posturing, a specific position the body assumes while experiencing a traumatic brain injury (TBI). Dedicated Dolphins fans likely thought back to a hit Tua suffered just four days earlier against the Buffalo Bills, which left the fresh-faced quarterback stumbling over his own two feet. Though Tua was cleared by a neurotrauma consultant and later returned to the Bills game, some were deeply concerned that Tagolaivoa might be suffering from Second Impact Syndrome (SIS)1 as he was taken off Cincinnati's field in a stretcher.

Thankfully, it seems that Tua has not suffered any sort of immediate catastrophic disability – on October 13th, less than two weeks after his injury at the Cincinnati game, Tagolaivoa returned to Dolphins practice sessions on a limited basis. By Week 7, he was back on the field. But for the 25 days between Tua’s injury and return, news of the quarterback’s condition was almost nonexistent outside of a brief statement posted to his Twitter and Instagram accounts.

Just as it is every week, the mood for the Week 4 episode of NFL Slimetime was upbeat, despite the events of the game Nickelodeon had just urged its viewers to tune in for. The program’s favorite ukelele-toting wunderkind was simply not mentioned at all, passed over without explanation in favor of the dozens of other athletes who managed to stay healthy that weekend. In fact, the show completely avoided covering any details of the Cincinatti-Dolphins match, instead opting to pretend that the game had perhaps never happened at all2.

I can’t say that I’m surprised that the shocking injury was deemed unsuitable for young audiences because it’s disturbing to witness as an adult. But Nickelodeon’s choice to omit the hit begs the question: why is a children’s network pushing content that it deems too violent for kids to fully handle in the first place?

The first step in finding out how the NFL ended up on Nickelodeon is to identify how the sport turned into a phenomenon. Perhaps unsurprisingly, Americans didn’t fall in love with the gridiron at first sight. For as long as there has been football, there have been concerns over its impact on the human body.

During the sport’s infancy, it hardly resembled the polished performances modern-day Americans religiously consume on chilly autumn evenings. It was an unbridled sport relegated to amateurs and college students, void of uniform rules or regulations. Early teams utilized military formations like the flying wedge to break through the human barriers that defenders would form in hopes of keeping opposing teams at bay. Helmets were viewed as optional accessories rather than safety requirements.

As one might expect, this style of play resulted in an alarming number of severe injuries and deaths. It was only in 1905, when President Theodore Roosevelt threatened to abolish the sport entirely, that drastic rule changes3 were implemented in an attempt to protect players. Organized professional football would emerge fifteen years later, and further adjustments to standard gameplay would continue well into the 1930s when the NFL published its first official rulebook.

Luckily for fans of the game, prevailing beliefs on football gradually softened between the 1930s and the 1950s for a number of reasons.

With one World War in the rearview and a second on the horizon, many proponents of the game made the argument that football could be a means of promoting physical fitness and preparing civilian men for battle without compulsory military service4. Some of the first Americans to adopt football were military academy students, and as early as the 1890’s one Harper’s Weekly article draws the comparison between war and sport, likening the gridiron to a “mimic battle-field”. Faced with looming threats of modern warfare, many Americans began to view football as a patriotic and noble endeavor, capable of engraining boys with much-needed masculine virtues.

Perhaps partially due to this sentiment, New Deal programs funded infrastructure like playing fields, stadiums, and grandstands across the country during the 1930s and 40s. Aside from providing ample physical space for games to take place (and observers to watch), such construction projects provided jobs for unemployed men in financially strapped communities devastated by the Great Depression. Almost overnight, the game of football became both a cultural and economic cornerstone in small towns across the country.

But the greatest tool football had in its battle to win over former naysayers proved to be the television.

Football, by design, makes for good television. From a logistical perspective, games are easy to schedule; a ticking clock inherently limits the duration of the game, and matches rarely drag into the lengthy overtime showdowns that plague baseball. Only the most extreme weather conditions are deemed significant enough to stop gameplay, all but eliminating the need for networks to plan alternate programming for rainy days. Frequent pauses in action prove to be perfect opportunities to slip in a few commercials.

But football also translates to the medium itself more effectively than other sports. Action is generally centralized around the line of scrimmage, in stark contrast to the frenetic pace of sports like hockey and basketball. The game is a series of digestible plays divided by short rests, rather than a ceaseless dance of players ricocheting from one end of a court to another.

One 1958 sudden-death NFL Championship game between the New York Giants and the Baltimore (now Indianapolis) Colts, nicknamed “The Greatest Game Ever Played”, is frequently cited as a watershed moment in the history of football. Aside from being the first championship game to ever go into overtime and boasting seventeen future Pro Football Hall of Famers, it was also the first football game broadcast nationally. It's estimated that 45 million people tuned into the game5, and immediately afterward the sport enjoyed a major surge in popularity.

Going into the 1960s, the narrative of football as a barbaric bloodbath was all but buried. Instead, people began viewing the sport as an arena for the country’s ultimate athletes to perform superhuman feats, a manifestation of American excellence in action. With many convinced of the game’s morality and merits, just one crucial aspect was needed to ensure the sport’s success for generations to come – a steady stream of young bodies.

Arguably, the moment Americans first began pushing football on boys rather than men came in 1929, when Pop Warner youth football leagues first emerged. Although Pop Warner is not the only youth football program in the US, it’s by far the largest – of the approximately 840,000 youth contact football players in the country, as many as half may be affiliated with Pop Warner teams6.

Initially, the intentions that fueled Pop Warner were honorable enough. In the city of Philadelphia, teenage vandals were constantly hurling rocks7 at the windows of factories. According to the Pop Warner origin story, one factory was dealing with as many as 100 shattered windows per month. Seeking solutions to this extreme nuisance, a man by the name of Joe Tomlin suggested that the owners of the vandalized buildings pool together funds to create an outlet for Philadelphia's street kids in the form of a youth athletic league8. Presumably, because this would be a much cheaper endeavor than constantly replacing windows, the business owners agreed to the proposal9. The reason that football was the sport of choice for this newfound project is comically simple - by the time Tomlin received the funds and was tasked with actually organizing a league, it was fall. Football seemed like a logical choice because it happened to be football season.

In the early 30s, when renowned coach Glenn “Pop” Warner arrived in Philadelphia to head the Temple University football team, the youth league was composed of 16 teams. Concerned by the increasing commercialization of the sport, Warner was immediately enamored with the program’s commitment to stripping down the game to its simplest elements as well as Tomlin’s efforts to connect his players with academic tutors when needed. As a result, Warner allowed Tomlin to attach his name to the youth league to help attract a wider audience.

At this point, there are two important distinctions to be made between pre-WWII and post-WWII Pop Warner football. Firstly, up until the mid-1940s, almost every Pop Warner participant was at least 15 years old. Some players were as old as 30. Furthermore, the Pop Warner league was highly localized. For the most part, teams were concentrated in the Pennsylvania-New Jersey-New York tri-state area. It wasn’t until the 1950s that children started participating in the game and a concerted effort was made to spread the league nationally.

Naturally, there was pushback at the first calls for youth contact sports. Many parents had completely valid safety concerns about their kids knocking the snot out of each other, and experts generally backed those concerns up10. Nevertheless, when Pop Warner Little Scholars became a national nonprofit organization in 1959, it gained a valuable ally in NFL commissioner Burt Bell. After learning about the program, Bell began promoting Pop Warner football to team owners in hopes of gathering additional support for youth programs (and perhaps, in turn, converting kids into lifelong NFL fans and future talent). But Pop Warner also quickly caught the eye of an individual far more influential than the NFL commissioner – Walt Disney.

In fact, Walt was so taken by the philosophy driving Pop Warner Little Scholars that he essentially created a two-hour promotion for the organization in 1960. Titled Moochie of Pop Warner Football, it aired nationally on ABC.

At the risk of getting sidetracked, I’d like to take a moment to talk about Moochie, because his tale perfectly encapsulates the dramatic shift in public attitude toward youth football culture that took place at the start of the 1960s.

Montgomery “Moochie” Morgan is a precocious kid somewhere between the ages of 9 and 12 years old, living in an idyllic suburb that could be situated anywhere in the continental United States. Right away, we learn that Moochie wants to be a football player, but cannot because he’s too small to play. This inspires Moochie’s father and neighbor Mr. Preston (who also happens to be a former college football star) to organize a Pee Wee Pop Warner team to accommodate the boys in town. Two bumbling elderly British men entirely unfamiliar with the sport are, for entirely unclear reasons, chosen to referee the Pee Wees. Side-by-side, adults, children, and audiences alike are taught the fundamentals of the game as well as the values that fuel the Pop Warner organization.

Conflict arises when the leader of the local Women’s Civic Circle catches wind of the town’s new Pee Wee team. While observing practice in the park, she witnesses Moochie absolutely pummel the team’s particularly bratty quarterback. Deeply concerned about the safety of the game, she complains to the mayor. This culminates in a city hall debate that threatens to ban the Pee Wee team from using community facilities.

On the day of the debate, the Civic Circle representative states her case despite heckles from the main characters concerning her age and lack of husband. A psychologist also advises against letting the town's children play football. Although he is the only medical professional consulted in this talk, his comments are also dismissed as gobbledygook. Meanwhile, Coach Preston and co. argue that banning the Pee Wees would be a violation of their constitutional rights and would leave their sons no other option than to cause trouble in the streets11.

Finally, Moochie takes the stand and offers to stop playing football if it means that the rest of his team can continue on. The townspeople are in awe of the young man’s willingness to self-sacrifice (because in their eyes, Moochie is a man rather than a boy – despite his rounded cheeks, the fact that his mother canonically still tucks him into bed every night, and his utter lack of understanding about local politics, the Disney special is very adamant about the fact that Pop Warner football transforms boys into men). One of the old British referees claims that Moochie’s admirable qualities were instilled in him by the Pop Warner program, and as a result the town council unanimously allows the boys to continue the tackle football program. The Women’s Civic Circle clucks in disapproval, but this is of no consequence as it’s demonstrated that their outdated opinions don’t really matter to this forward-thinking football-loving town. The Pee Wee team goes on to become the best in the country, and as a reward, they’re all sent to Disneyland12. The End.

Writing it all out, it’s evident that Moochie of Pop Warner Football is propaganda at its most blatant. But when broadcast to viewers across the country, it absolutely made an impact in changing people’s attitudes concerning youth football programs, and Pop Warner's popularity skyrocketed. For context, in 1956, the New York Times estimated that approximately 90,000 children were playing on 2,000 organized youth football teams across the US. By the time 1965 rolled around, the journal Physicians’ Management estimated that 800,000 boys between the ages of 9 and 15 were playing in organized football leagues. Over just ten years, parental anxieties over serious injury yielded to a far greater fear – what would become of their sons if they didn’t have access to football.

From its start, Pop Warner leagues made promises to use football as a means of keeping kids disciplined both on and off the field. But whenever the future of youth football is threatened, advocates of the game morph those promises into threats. During Moochie’s climactic city hall meeting, we see that tackle football is justified because the danger of the game is outweighed by the implied societal dangers presented by testosterone-fueled boys left to their own devices. Scarier still, though, were the threats presented by Band-Aid-toting mothers, perched nervously on sidelines. This manufactured bogeyman, with her constant coddling and apprehension over the game’s violent aspects, threatened to emasculate the men of tomorrow. As football’s popularity steadily increased in the United States, the notion that the sport may not be suitable for young children seemed increasingly old-fashioned and unfounded. With new rules and equipment standards in place by the 1950s, it became easier to disregard the safety apprehensions of skeptics, be they the Civic Circles of a Disney universe or real-world mothers. Though individual concerns never ceased altogether, more and more parents became willing to put their worries aside out of fear that irrational overprotection might inadvertently weaken their boys.

These arguments and attitudes helped justify the continuation of youth football following Pop Warner’s first recorded fatality in 1964. When 14-year-old Keene Mitsuru Yamamoto lost consciousness and died following a blow to the back of the head sustained during practice, it was brushed off as an anomaly rather than an inevitability. As little as two years after the incident, the Vice President of the American College of Sports Medicine would erroneously claim that the Pop Warner program had never suffered a fatality. The narrative that the practices of youth football leagues posed little to no danger continued without opposition well into the 1990s.

And just like that, football started attracting younger and younger fans. But thanks to a major NFL media makeover in the 1970s, it wasn’t just a love for the game that motivated the most dedicated child athletes to take to the field. Instead, it was the faint but ever-alluring opportunity to become a star.

The NFL developed into the mega-corporation it is today sometime during the 1970s. Aside from the rapid rise of football on a community level, the NFL’s fanbase expanded after the absorption of a flashier, more camera-conscious rival upstart known as the American Football League (AFL). After joining forces with their former competition, the NFL adopted rule changes and minor tweaks (such as adding names to the backs of jerseys) that generally made for a more dynamic game to watch from the living room. Simultaneously, NFL commissioner and general marketing genius Pete Rozelle sold the broadcasting rights to professional games in a series of revolutionary deals between the major television networks of the era. From the 1970s onward, fans have been able to tune into almost every game on either CBS, NBC, or FOX13. Finally, it was during this decade that businesses fully realized the commercial value of a star football player. After witnessing legendary quarterback Johnny Unitas' ability to sell anything from soup to socks during the 50s and 60s, the NFL began consistently churning out the sort of ultra-visible superstars that served as both ambassadors for the league and role models for aspiring athletes.

All of these factors combined to create an environment in which any child old enough to turn on a television could easily access and follow superhuman behemoths pull off extraordinary feats of strength, dexterity, and speed, seemingly impervious to injury outside of occasional grass stains14. And for years, things stayed that way. With programs like Pop Warner having successfully convinced Americans of the sport's virtues and relative safety, some boys (and their parents, by proxy) began pouring all of their hopes and dreams into going pro. For those unable to reach their lofty childhood goals, an entire culture around the NFL developed to fall back on and fuel another generation of talent.

But, as most already know, the fantasy of football as a harmless pastime without ill effect couldn’t last forever. In the 1990s, concerns echoing those expressed a century beforehand resurfaced, this time centered around the invisible effects of repetitive brain trauma rather than the outright mangling of bodies. The NFL was able to quell the issue for a little while with the 1994 creation of the Mild Traumatic Brain Injury Committee, even though chair Dr. Elliot Pellman lacked any previous experience in neurology as well as the fact that the committee didn’t actually seem to do much to change guidelines surrounding head trauma. However, the identification of neurodegenerative disease CTE in football players around 2005 – and the slew of post-mortem diagnoses that have cropped up in the two decades since – has finally made it more difficult for people to pretend that everything surrounding the sport is alright.

The full scope of how much CTE impacts football players is still uncertain, as the disease can only be diagnosed with absolute certainty after death. All the same, experts have begun sounding the alarm concerning the potential hazards. The 2013 documentary League of Denial flanked by the film Concussion (2015) finally informed the general public about what the emerging health crisis might be doing to their pro athletes – and, more importantly, their children.

Over the years, it has become increasingly clear that children are just as susceptible to CTE as seasoned stars. Though a recent study from the Journal of the American Medical Association shows little correlation between football participation and test performances in 9-12-year-olds, neurologists at Boston University have found that earlier exposure to tackle football heavily correlates with earlier onset of CTE symptoms. CDC findings show that the average youth tackle football athlete experiences around 378 head impacts per season and now urges children under the age of 14 to instead participate in flag football or non-contact programs.

Though football is certainly still alive and well in America, this data has all the same led to noticeable declines in youth football participation. And this, perhaps more so than anything, maybe the scariest finding of all for those heavily invested in the profitability of professional sports. After all, football is a young man’s game – the generation playing now will soon be too battered to play, necessitating that the youth football players of today be there for the matchups of tomorrow. But with preliminary studies showing as many as 99% of NFL players suffering from symptoms of CTE, for many the prospect of career football is quickly morphing from a dream to a nightmare.

As a result, the NFL and its associates have had to get creative in finding ways of hooking young blood to the sport and continuing the lucrative cycle already in place.

Some of the most effective strategies have come from introducing the game to fans in ways that eliminate the violent realities of the sport. For fans too young to fully dive into the odds and statistics and predictions of sports gambling and fantasy football, the advergame works just as well. Franchises like Madden NFL are able to simultaneously draw fans in with the glamour of high-profile athletes and promptly strip the star proxies of their brains and bodies and humanity in an artificial environment where it’s impossible to suffer a concussion or even feel pain at all. But, as powerful as video games and virtual realities may be, they are not enough on their own to continue justifying the actual harm that athletes suffer.

So, in the war to keep contact sports an integral part of American culture and economics, football has fallen back on its oldest and truest ally for support - good old-fashioned television.

It’s not as if NFL Slimetime is the only show out there that glorifies football. Netflix’s Last Chance U and Coach Snoop feature young people being “saved” from real-life difficulties by the structure that sport supplies. Archie Andrews of teen drama Riverdale once lamented that a troubled peer of his had never experienced “the triumphs and defeats, the epic highs and lows of high school football”. NFL Slimetime isn’t even Nickelodeon’s first foray with the pigskin – 2012 introduced a bizarre short-lived animated superhero series called NFL Rush Zone and in 2015 the children’s network launched a live-action female-led sitcom in Bella and the Bulldogs.

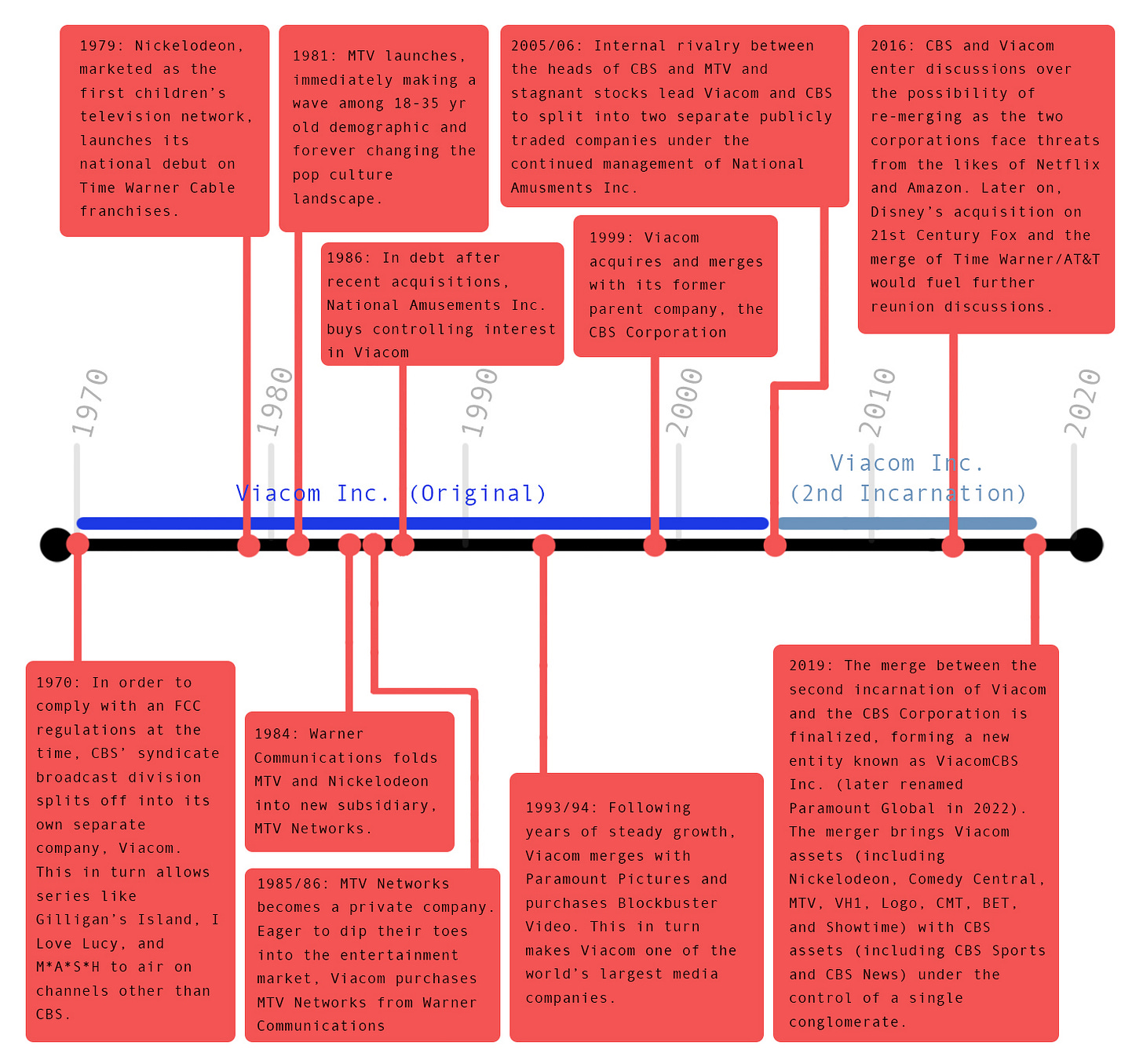

It’s also not particularly surprising that Nickelodeon, specifically, produces programs that encourage kids to take up an interest in football. CBS, which has profited off of NFL broadcasts for years, has long been entangled with Viacom, Nickelodeon’s parent company. Their history is a complicated one (if you care to understand it in full, I’ve included an abbreviated timeline of CBS/Viacom events), but what’s remained generally true throughout the years is that both entities benefit from one another’s successes. In 2019, Viacom and CBS merged to become Paramount Global, tying the NFL and Nickelodeon’s interests even closer together.

But even without the behind-the-scenes business dealings that made linking up so convenient, the symbiotic relationship between the NFL and Nickelodeon is an incredibly logical one.

For Nickelodeon, the NFL provides valuable assets such as access to game footage and connections to high-profile celebrity athletes. What’s more, working with the NFL looks good for Nickelodeon because the channel has spent a lot of time and money pushing the message that they care about children’s health and wellness. Though a 2013 study suggested that nearly 70% of food-related ads on the children’s network were for “junk and fast food”, since the early 00s Nickelodeon has enacted all sorts of initiatives to create the perception of fighting childhood obesity. Until 2019, the channel would temporarily shut down once per year for a “Worldwide Day of Play”, and at the height of the Nintendo Wii’s popularity, Nick released a fitness-themed video game featuring Dora the Explorer and the Backyardigans. I can vaguely recall viewing a Nick-produced PSA for “Hidden Sugars” as a preteen, snug between advertisements for Kraft macaroni and cheese and McDonald’s Happy Meals. Though the National Football League has faced scrutiny over the deteriorating mental health of its players, there’s no denying that the most prominent figures appear to be physically fit. And for Nickelodeon, that superficial appearance of health is all that’s necessary.

Meanwhile, Nickelodeon has something that the NFL desperately seeks – the trust of its viewers. And, more importantly, the trust of its viewer’s parents. For every child anxiously tuning in for a glimpse at the latest installment of Paw Patrol, there’s a set of parents who were once raised on a steady diet of Spongebob, Catdog, and Ren and Stimpy. With endless (completely warranted) nightmare stories relaying the horrors youngsters manage to dig up while unsupervised on outlets like YouTube Kids, Nickelodeon has understandably become a dependable, reputable source for child-appropriate media. The NFL knows all of this and is more than willing to use the trust that people have in Nickelodeon to try to improve its own image. As disturbing as reports of neurodegenerative disease in former football players is, reframing the sport as something that kids can have fun with and follow along undoes some of the bad press. It’s the same strategy that Pop Warner leagues used in partnering with Disney 60 years ago, just with a different precocious kid at the helm. Whether it’s coming from Nickelodeon or Walt Disney himself, there will always be parents who believe that content created especially for kids couldn’t possibly be that dangerous.

And that is precisely what makes NFL Slimetime so uniquely insidious.

Slimetime is edited and animated for children that can’t possibly understand the serious repercussions that professional athletes take on when putting themselves on the line for entertainment. More often than not, the collisions and crashes that might be slowly damaging players’ brains are censored with geysers of slime or explosions of sparkles. Like a Madden video game or your fantasy football league, there are no real injuries to witness in Nickelodeon’s idealized iteration of the sport. It is a program perfectly designed to hook kids on the game and convince a new generation to grab the ball and pick up where the crumpled bodies of their predecessors collapsed.

As was evident through Tua Tagovailoa’s treatment and temporary disappearance following that fateful Thursday night game in September, no one player is so valuable that they cannot be replaced.

Though flesh-and-blood players might pause for a moment to take a knee for comrades carried away, underneath a colorful facade Slimetime illustrates just how willing we are to turn our eyes away from the fallen. And, in the perpetual push past all of the carnage left the wake of competition, it’s our kids who are bound to get caught in the current, damaged before they can fully realize that something is wrong.

If you enjoyed this essay and want to say thanks, please consider buying me a coffee 😎

Second Impact Syndrome is rare and not yet fully understood, but occurs when an individual suffers a concussion before symptoms of an earlier concussion have fully resolved. It is often fatal and can result in the brain death of an otherwise healthy person in as little as a few minutes. It also may leave surviving recipients severely disabled.

In fairness, the short format of the show means that there isn’t time to cover the details of every game. That said, I don’t think it was a coincidence that the Dolphins, who had received heavy coverage on the show prior to Tua’s injury, were passed over on the October 5th broadcast.

Notably, the line of scrimmage and the forward pass were introduced to the game to try to keep the ball moving down the field and the players from barrelling into a hyperviolent dogpile.

As Kathleen Bachynski describes in her book No Game for Boys to Play, there was a perceived need for increased physical fitness among the general American populace following World War I, when reports claimed that one-third of men called for military service were deemed physically unfit. This is also, in part, why physical education programs were added to public school curriculums.

This is particularly impressive, as many New York Giants fans couldn’t tune into the game because it was blacked out in the Greater New York area.

Getting a definitive percentage of how many children play contact football through Pop Warner is difficult – the official website claims that 400,000 kids aged 5-16 participate in Pop Warner programs, but it’s unclear what fraction of that number represents children participating in cheer, dance, or flag-football programs. In addition, while the 840,000 total player count is sourced from USA Football, the governing body for amateur football in the United States, it’s unclear whether that reflects the number of children playing for the 2022 season or reflects numbers from years past.

I wish I had the faintest clue about why kids were evidently throwing so many rocks in Philadelphia in the 1920s, but sadly I do not.

At this time, educators were hesitant about hosting competitive athletics through schools because of the safety liabilities and expenses involved with doing so.

Interestingly, it’s never mentioned whether or not the formation of Pop Warner football had any measurable impact in actually solving this problem.

For instance, a 1938 statement from the American Association for Health, Physical Education, and Recreation reads as follows:

”Inasmuch as pupils below tenth grade are in the midst of the period of rapid growth, with the consequent bodily weaknesses and maladjustments, partial ossification of bones, mental and emotional stresses, physiological adjustments, and the like, be it therefore resolved that the leaders in the field of physical and health education should do all in their power to discourage interscholastic competition at this age level, because of its strenuous nature”

This is funny because Moochie’s Pee Wee team is brand new and there’s absolutely no indication that youth vandals were a problem in this perfect fictional suburb previously.

That’s right! This two-hour special was an advertisement for the (then brand new) Disney theme parks as well as an infomercial for youth contact sports!

ABC/ESPN and the NFL Network also have the rights to certain special games, such as Monday Night Football and the primetime game that airs on Thanksgiving day. Important to note is that FOX did not acquire an NFL contract until the mid-90s, meaning that the majority of the games broadcast between 1970 and 1994 were split between NBC and CBS. Today as a loose rule, CBS airs most AFC games, while FOX covers most NFC matches.

Obviously, there were occasional injuries too horrific to ignore, such as the infamous Joe Theismann leg injury of 1985. However, for the most part, audiences are not subjected to outright blood or gore, often making it easy to downplay the severity of injuries on the field.