Along the side of the New Jersey Turnpike, where the Hackensack River delineates where Seacaucus ends and East Rutherford begins, a jumble of off-white walls and glass peeks through waving reeds as tall as men. It’s easy to miss, when you’re speeding along at 65+ miles per hour, intent on getting to (or away from) New York City as quickly as humanly possible. Most of my friends and family members who have settled near that transitory space between New Jersey and New York claim to have never even noticed the 3,000,000 sq feet the complex encompasses – even though the land itself is punctuated with a 20-story Ferris wheel. From the highway, along the side of one of the white walls, you can see black capital letters that bear the property’s name: “American Dream”.

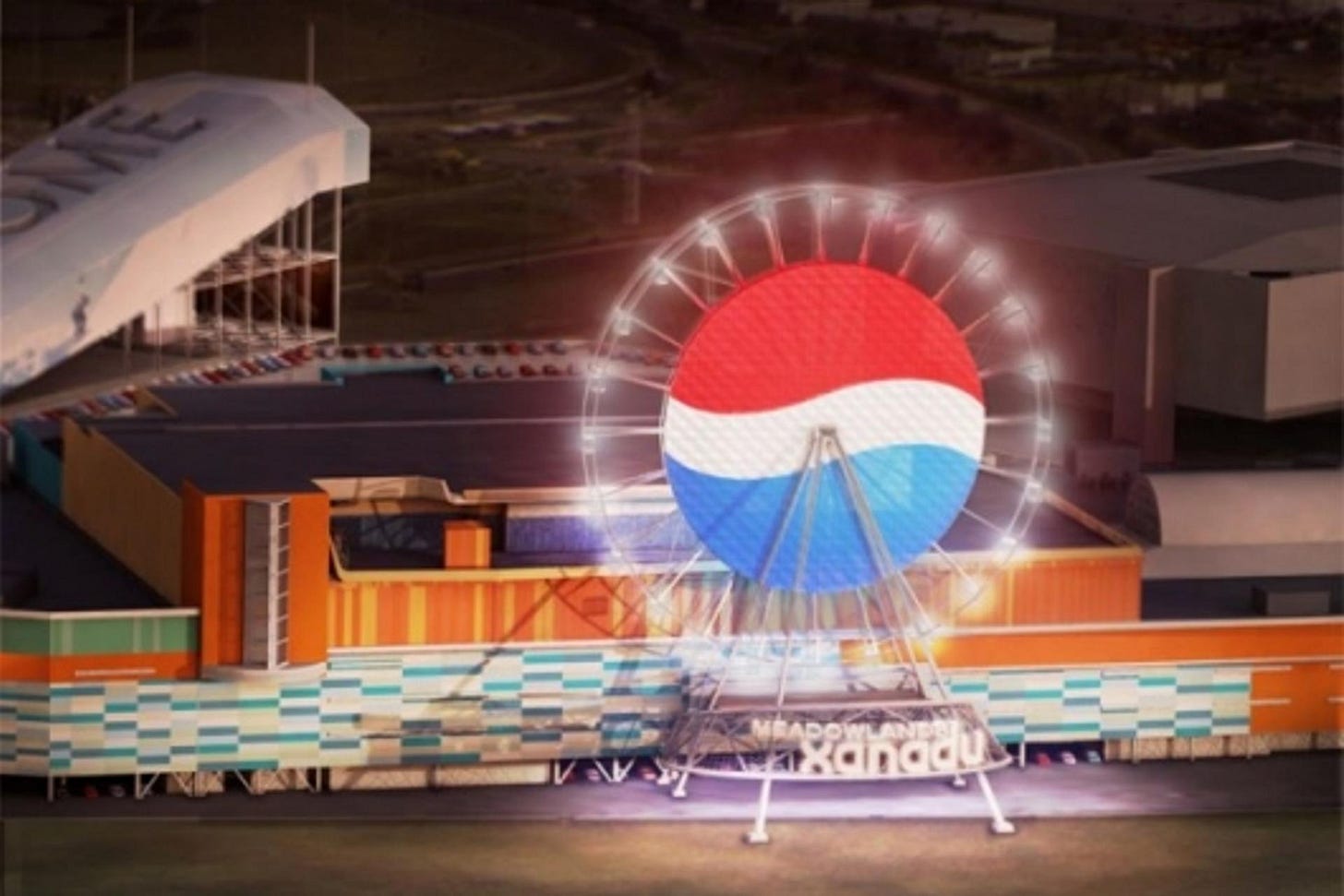

The white walls and glass facades and the giant Ferris wheel that comprise American Dream have not always been there, of course. The walls used to exist where De Stijl meets shipping containers, loud and loathsome in shades of red and orange and blue. Former governor Chris Christie once called it “by far the ugliest damn building in New Jersey, and maybe America”.

Before that, the space was used as a parking lot for people hoping to see a sporting event at one of the neighboring sport venues. Before that, man-made “meadows” of salt hay occupied the area. And before that, there were great swamp cedar forests that sheltered elks and wolves and mountain lions that have long since been driven out of the Garden State.

The colorful, segmentary version of this space – the version that everyone seemed to despise most – is the one that exists most vividly in my mind.

I don’t have memories from inside those colorful boxes. No one does, because they were never opened to the public.

But I do have a few dozen fused memories of the sight from the backseat of the car, usually on the way to or from my grandparent’s wood-paneled house in Albany. It was a visual landmark that signified how far along we were in our journey (two hours down and three to go, or vice versa). I had no idea what the purpose of the landmark was, because the internet was still young and so was I, but wondering what it could have been was a welcome exercise to occupy my mind during car rides that never seemed to end. It was not until adulthood that I learned that those perpetually shuttered barriers were meant to house the third-largest mall in North America.

When I was passing by it with some regularity, it was not yet known as American Dream. Instead, people called it Xanadu.

Naming the thing Xanadu was likely the first clear-cut, definitive mistake that developers made in a long series of mistakes. More likely than not, Samuel Taylor Coleridge's 1797 poem Kubla Khan inspired the title. Cursory research would have revealed that the flowery language describing a “stately pleasure dome” called Xanadu, conceived in an opium-induced haze, is famously a fragment. An unwanted visitor interrupted Coleridge’s creative fervor, and the poet never found the words necessary to complete the composition. Likewise, the name Xanadu conjures visions of the fictional manor from the wildly famous 1941 film Citizen Kane. Said to be “the costliest monument a man has built to himself”, the unfinished estate ultimately falls into disrepair and becomes an opulent prison as its landlord wastes away, empty and alone.

These wretched omens were lost on the Mills Corporation, the real estate investment trust who first proposed the idea of building the combination mall/hotel/office space that would come to be known as Xanadu in 1994. During the earliest stages, Xanadu was slated to sprawl across 206 acres of wetlands in Carlstadt, NJ.

For those unfamiliar, the wetlands of northeastern New Jersey – more commonly known as the Meadowlands – are infamous for the sheer magnitude of environmental abuse they’ve endured. Landmass generated through New York City dredging has quite literally altered a landscape completely depleted of natural resources. Viewed for many years as useless, it was used as a giant landfill both legally and illegally. Carcinogenic chemical waste poisoned marshes for a century. It wasn’t until 1969, with the creation of the Hackensack Meadowlands Commission1, that anyone attempted to correct (or even acknowledge) the devastating impact years of human fuckery had had on the wetlands.

The moment the Mills Corporation revealed its plans to the general public, people – specifically, the people of Carlstadt, NJ – were pissed. The hypothetical development would inherently destroy hundreds of acres of land mid-recovery, which served as a habitat for hundreds of waterbirds eager to feast on the mud crabs and herring capable of thriving in the brackish swamps. Mills, following in the footsteps of corporations past, argued that the land was useless, ransacked beyond repair by toxic pesticides and invasive species.

The disagreement led to years-long investigations by the EPA and the US Army Corps. In the end, Gov. Jim McGreevey refused Mills Corp. the building permits necessary to move forward with the project. The Meadowlands Conservation Trust then purchased the land and renamed it the Richard P. Kane Natural Area, permanently protecting that specific segment of the Meadowlands.

Back at square one, Mills ventured five miles north, to the neighboring borough of East Rutherford.

There, the New Jersey Sports and Exposition Authority (NJSEA) had issued a request for proposals. With the New Jersey Devils hockey team slated to move to Newark and the New Jersey Nets basketball team slated to ship out to Brooklyn, the newly abandoned Continental Airlines Arena2 sought to restructure following the departure of its major tenants. Looking to make use of what would otherwise become a sprawling, dormant parking lot, the board of the NJSEA chose the Mills Corporation’s Xanadu project over a slew of competing proposals in 2003.

As ground broke in 2004, Mills Corp. CEO Laurence Siegel claimed that the "new standard for bringing lifestyle, recreation, sports, and family entertainment offerings together in one location" would be open for business in approximately two years. And those two years couldn’t have passed soon enough. At the time, estimates projected that Xanadu’s tax payments would total approximately $133 million USD annually, which would then be funneled directly into state and local coffers. Furthermore, the catalog of amenities Mills promised was truly astounding, among which included a facility dedicated to extreme sports, both rock and ice climbing venues, and a baseball diamond for minor league games3. Luxury spas, a large-scale children’s amusement center, and multiple fine-dining restaurants were slated for development as well. The public was assured4 that what was to come would be more than another bloated shopping center – mighty Xanadu would be a visually arresting “regional colossus with massive drawing power”.

But, as the adage goes: when something sounds too good to be true, it usually isn’t.

In 2005, the SEC began an informal inquiry into an alleged array of “accounting errors” made by the Mills Corporation. By early 2006, that informal inquiry was upgraded to a formal investigation. Stocks plummeted, and the company was forced to shave off 60% of the earnings reported between 2003 and 2005. Space in the incomplete mall became increasingly difficult to lease, making banks less willing to finance the project. There was no way the Mills Corporation could continue to fund the colossal Xanadu, let alone survive as a company.

So, having bitten off far more than they could chew, the Mills Corporation was forced to sell Xanadu for $500 million USD to a cluster of private investors led by real estate investment firm Colony Capital. Colony moved the opening date back to 2008, frustrating the increasingly impatient (but ultimately powerless) citizens of New Jersey. In hopes of quelling the public’s bellyaching, even more fantastic assurances were issued. There were claims that anchors would include a concert hall, an “Egyptian-themed movieplex”, a combination bowling alley/martini bar, and a Cabela’s retailer complete with an artificial river for indoor trout fishing. When the acquisition generated much-needed construction funds, plans for a massive London Eye-esque Ferris wheel to be sponsored by PepsiCo. were announced. Theoretically, tens of thousands of jobs would be generated to support something so grand, super-charging the local economy.

Even so, the mere mention of Xanadu seemed to elicit a chorus of groans from the residents forced to live alongside it. It was an expensive, functionally useless eyesore in the minds of folks across the Garden State, a big empty shell filled only with hollow promises of greatness. Laurence Siegel, who retained his creative leadership position on the Xanadu project following the 2007 dissolution of the Mills Corporation, argued that the public’s criticism was premature, comparing it to “judging the Sistine Chapel after Michelangelo put on the first coat of paint.”

At a snail’s pace, progress inched forward. Conversely, the price tag to complete Xanadu continued to skyrocket. Originally projected to be a sizable $1.3 billion USD expense, by the start of 2009, at least $2.3 billion USD had been sunk into the still-unfinished megamall.

But in March of that year, one of Xanadu’s primary construction lenders – a non-bankrupt affiliate of recently-bankrupted Lehman Brothers Inc.5 – defaulted on loan obligations. Though construction was nearly 80% complete and approximately 70% of the space inside the mall was already leased, the operation came to a standstill. There simply wasn’t any money left6.

Developers scrambled to find new lenders (or restructure relationships with existing lenders) to no avail. As it became increasingly clear that no one intended to toss the floundering Xanadu a life preserver in the form of a bailout, a mass exodus of tenants commenced. No more recession-proof than their behemoth landlord, many renters had no choice but to curtail expansion into the Meadowlands if they hoped to stay afloat. Finding replacement tenants was a struggle. Understandably, most businesses were unwilling to shell out money for a slot in a perpetually cursed venue.

Months of inaction became years. That is why Xanadu exists as something static in my head. Without funding to pay construction crews, the lot was forsaken. The world continued to move – my grandparents moved out of that wood-paneled house in Albany, and I moved the hell out of New Jersey. Even so, Xanadu stood still.

Chain-linked fences kept the world out, save for the bits of nature desperately trying to reclaim what rightfully belonged to it. Broomsedge and goosegrass and ragweed and all sorts of other greenery that humans deem noxious sprouted from pavement cracks. In 2011, after two years untouched, a snowstorm caused the ceiling of the mall’s virgin indoor ski slope to collapse.

Hope came in the form of a conglomerate known as the Triple Five Group. The owners behind the West Edmonton Mall and the Mall of America, Triple Five had made a bid for the site back in 2002, when NJSEA was accepting proposals to make use of the abandoned parking lots of Continental Airlines Arena. Where the entire state of New Jersey saw a hulking monument to opulence and ineptitude, the real estate giant saw an opportunity.

In cooperation with the NJSEA and the lenders that owned Xanadu’s debt, Tripe Five gained ownership of the project. Their first order of business was a name change. Overnight, Xanadu became American Dream.

The retitling was far from the only change made in hopes of ensuring American Dream’s success. Plans were made to replace the god-awful facade with clean white panels. Governor Chris Christie, believing wholeheartedly that the project was too big to fail, pledged $180-200 million USD of NJ taxpayer money to the building’s completion. In a truly unhinged move, considering the property’s contentious past, Triple Five proposed going even bigger with the American Dream project. An indoor amusement park, a water park, and a regulation-size NHL ice rink were added onto the docket. A bus hub, a train station, and even a few helipads would be added to chauffeur shoppers from New York City. What’s more, Triple Five vowed to have the doors of American Dream open in time for the fast-approaching 2014 Super Bowl, which was to be hosted at the neighboring MetLife Stadium.

Ironically, the New York Giants and the New York Jets worked together to stop that goal from happening. The NFL welcomed Xanadu, the retail-centric megamall, because Bergen County blue laws7 would stimy hoards of shoppers from visiting on Sundays during football season. But American Dream, the all-in-one amusement complex, was another story entirely and would remain relatively unobstructed by the blue laws. The Giants and Jets feared that changes in the American Dream layout would create a catastrophic traffic nightmare, which could drive away fans. They filed a suit against Triple Five, and Triple Five filed a countersuit in return, with both parties thoroughly convinced that the demands of their adversary would infringe upon the success of their business.

All the while, no progress could be made on the still-ugly, still-languishing structure.

It was not until 2014 that the unstoppable force and the immovable object reached a tentative agreement. Having been left to the elements for six years, developers estimated that an additional $2 billion USD would be necessary to finish off the once nearly-finished behemoth.

But, at the very least, the process of rebuilding could start once more. At least, for a little while. Before too long, American Dream drained Triple Five’s funds, just as mercilessly as it had previous undertakers. Construction stalled once more, like clockwork. Ultimately, NJSEA issued $1.15 billion USD in bonds to help revive the project that seemed to want nothing more than to sink back into the swamp surrounding it. Said bonds were issued in 2017. Developers also managed to secure an additional $1.67 billion USD in financing, which finally, finally allowed American Dream to approach completion in 2019.

Triple Five announced that the Nickelodeon-sponsored indoor theme park and skating rink would open for business on October 25, 2019, and Big Snow American Dream (aka the much-maligned indoor ski slope) would welcome guests on December 5th. The rest of the mall – which encompassed 350 shops, 100 eateries, and the DreamWorks-themed water park – was slated to open in March 2020.

The completed mall did not open in March 2020.

Instead, in a particularly cruel and comic twist of fate, the COVID-19 pandemic forced all American Dream operations to shutter on March 8. For 207 days, state quarantine restrictions emptied the corridors once more. As if reliving a bad dream a decade past, major retailers pulled out from the mall in the face of financial ruin. Both Forever 21 and Lord & Taylor – two of the mall’s six retail anchor tenants – were forced to liquidate all brick-and-mortar locations. Stores facing imminent bankruptcy, such as Barney’s New York and GNC, were forced to withdraw as well.

But in October 2020, despite the universe’s noble struggle otherwise, the mall was at last allowed to open (albeit at limited capacity). Almost four years have passed since, though not without the occasional calamitous mishap. An electrical issue set fire to the indoor ski slope in October 2021, closing the attraction to visitors for months. In February 2023, a large decorative helicopter suspended from the ceiling fell and spectacularly crashed into a swimming pool filled with customers, injuring four. Last Black Friday, an unfounded bomb threat forced the American Dream to evacuate customers, striking fear and interrupting the most profitable day of the fiscal year. And just a few weeks ago, four unidentified individuals managed to rob $100k worth of merchandise from the mall’s flagship Balenciaga store.

This past May, I finally carved out the time necessary to pilgrimage the American Dream. My drives through New Jersey have grown fewer and further between as I’ve aged and sown roots elsewhere. Nevertheless, witnessing this looming shrine to consumerism firsthand has felt necessary for quite some time. No longer is the mall a stagnant landmark of nebulous contents, forever destined to be passed by in transit between Point A and B. Now, it is something far more fleshed out and fucked up.

American Dream’s most striking aspect is its emptiness. Though I visited on a Friday evening, the corridors of the complex were deserted. Vast swaths of space remain unleased. On a few occasions, I encountered staircases abruptly interrupted by ceiling, meant to lead to a fourth floor that does not yet exist.

It is a liminal space, unfit for lingering or loitering. Unsettling murals, the garish bastard children of pop art and rococo, surround you with scenes like this:

Fountains in the promenade of the mall’s luxury wing feature fountains adorned with islands of ornamental plants unfit to survive the swampland outside. Around the greenery are schools of a dozen or so koi, who swim in an endless counterclockwise circuit and slowly go mad in prisons free of stimulus. Discounting hapless employees manning the customerless likes of the Ferrari showcase or the Gucci storefront, I saw more fish than I did people.

This vacancy was not unique to the luxury wing, either. Looking down from a third-floor balcony, I spotted just one skater gliding along the NHL regulation-size ice rink. The same was true for the Angry Birds miniature golf course. Only a handful of diners sat down at the MrBeast Burger, which attracted thousands of the Youtuber’s devoted fanbase upon opening8. As they pecked at their sandwiches, a MrBeast video featuring jumpsuit-clad participants participating in a Squid Game recreation played on a massive flatscreen television9.

Even the Nickelodeon Universe indoor theme park, one of American Dream’s costliest endeavors, was eerily quiet. I sat for a while in a chair shaped like a hand, situated just outside the ticketing area10, and watched riderless cartoon-themed roller coasters. I thought about the first date I ever went on, which was at a mall in New Jersey, too. Had any awkward middle schoolers ever shared a first kiss seated in the cold, plastic palms of those hands? There’s no way to know for sure, but something about the outwardly artificial whimsy of that particular area seemed incompatible with something as human as hormone-fueled teenage passion.

Down the hall from the Nickelodeon theme park is the Dreamworks Water Park, which was closed and obstructed from view. It’s home to North America’s largest indoor wave pool, which the neurotic and cynical part of me knows will be the death of someone any day now11. One of the most popular rides in the park is a tube slide, which is Shrek-themed. Toward the end of the slide, patrons zoom by an effigy of the green ogre sitting on the can, smiling. In that moment, they are turds, circling the bowl without agency before being flushed away. Whether this is deranged commentary of some sort is hard to say.

The cherry on top of this fever dream was the 34-foot replica of the Statue of Liberty, constructed out of over 3.5 million congealed jelly beans, which stands outside of the IT’SUGAR candy store. The universally recognized stand-in for the concept of “The American Dream”, condensed into a sickly sweet monument, towers and pleads that passersby drop a few dollars on food nutritionally incapable of nourishment.

The more detailed a portrait of American Dream you paint, the greater the temptation to ask why becomes. Who is this for? What’s the point? Is there a point? Why???

To seek some semblance of an answer to this truly unanswerable question, I looked into the Triple Five Group, the conglomerate that owns and has shaped American Dream as it exists today.

Despite being a conglomerate, Triple Five is also a family business, headed by the billionaire Ghermezian family. Of Iranian Jewish descent, the Ghermazian family made a fortune over several generations by selling rugs. With dreams of something bigger and better, the family emigrated to Alberta – not America – in hopes of striking oil on cheap, largely unused farmlands. Though their initial search was unsuccessful, they profited tenfold when the government sought to buy back the farmland to create green space around the city of Edmonton. Ever since, the Ghermezians have stuck to the business of supermassive real estate ventures. In 1981, they developed the West Edmonton Mall12, which was followed by the Mall of America13 in 1992.

The Ghermezian family is quiet, the sort of family that takes great care not to do much in terms of public appearances. However, as Orthodox Jews, the Ghermazians will from time to time speak to congregations and yeshivas on the intersection of business and faith. This is where one must turn to find answers concerning the motive behind the mall.

In short, according to American Dream CEO Don Ghermezian, the family’s ultimate goal is to use the mall as a vessel for tzedakah.

A core tenet of Judaism, tzedakah is an ethical obligation14 to give, regardless of financial standing, in hopes of empowering and supporting those most in need. For many Jews in modernity, tzedakah is practiced through charitable donation, though tzedakah itself doesn’t fit neatly into Western conceptions of charity. A more accurate translation of the word, from Hebrew to English, would be “righteousness”. In this case, the Ghermezians hope to make as much money as possible through American Dream so that those funds could be returned to and distributed among the community at large.

Tzedakah is a beautiful (and frankly, radical) concept, and it’s easy to fall in love with the idea that something that seems capable only of taking could be something more than a quick cash grab gone wrong. How sincere the Ghermezian’s sentiments are is anyone’s guess15. Only they know the truth that lives inside their hearts.

But what their true intentions are almost doesn’t matter because, in practice, the operation is not playing out as planned. Despite being fully open in a world (mostly) free of plague, American Dream has continued to hemorrhage money. In March 2021, Triple Five was forced to hand over a 49% stake in both the West Edmonton Mall and the Mall of America as collateral on a billion-dollar construction loan. Between 2021 and 2022, the megamall’s losses quadrupled. After one bond payment in 2022, the developers were left with a balance of just $820.23 USD in their account. Neighboring towns claim that they’re owed no less than $13 million USD in payments by American Dream, and earlier this year a group of junior lenders successfully sued for $389 million USD after American Dream defaulted debt. Though Triple Five has managed to secure financing through 2026, the long-term future of American Dream is as murky as ever.

Nevertheless, Triple Five has doubled down and laid out plans for a second, grander American Dream16 location in Miami, Florida. If completed, it will be the largest mall in North America. However, at the rate the project is going, it seems just as likely that the sea will swallow the whole thing up before it can be fully realized. After all, that’s what the wetlands of New Jersey, fueled by dreams of swamp cedars past, have been trying to accomplish for years.

In the void between a mostly empty Szechuan restaurant and a mostly empty Italian bistro, I stumbled upon a sprawling fountain during my visit to American Dream. It wasn’t filled with koi, but scattered along the bottom were coins. They were few and far between - prayers and wishes for something better, I can only assume. Or perhaps, in a twisted and perverted way, the $7 USD or so in pennies and quarters is tzedakah. Maimonides, a 12th-century Sephardic rabbi, once laid out an eight-tier hierarchy of how best to practice tzedakah. It reads something like this:

Ranked first is giving in a way that allows another person to become self-sufficient. If you teach a man to fish, you feed him for a lifetime, et cetera.

But right underneath that, in terms of perceived goodness, are anonymous donations made out to unknown recipients. I don’t think it’s feasible to track down who flicked those coins into the water, against better judgment. God only knows who ends up with those coins eventually.

Perhaps, if anything, there is a mitzvah buried somewhere in that chlorinated water.

Regardless, ever the insatiable middleman, the American Dream welcomes whatever it can take.

If you enjoyed this essay and want to say thanks, please consider buying me a coffee 😎

(Later known as the New Jersey Meadowlands Commission).

Continental Airlines Arena would become the IZOD Center in 2007, and later down the line, Meadowlands Arena.

The Bergen Cliff Hawks, a team that never actually came to fruition, would have called the stadium home. Years of stagnation at Xanadu would stall the team’s formation, culminating in the cancellation of the ballpark in 2011, which squashed all remaining hopes of Bergen manifesting a baseball team.

Assured not just by the Mills Corporation, but by New Jersey politicians as well. In a 2015 federal racketeering trial, it was revealed that Mills paid former Bergen County Democratic leader Joseph Ferriero $35,000 USD per month in consulting fees, which may or may not have been in exchange for his political support. A former Mills employee who testified at the trial described “a web of lobbyists” who negotiated political contributions in exchange for public support of Xanadu. In particular, disgraced New Jersey senator Bob Menendez was referred to as a “weapon of mass destruction” for persistently pestering the US Army Corps of Engineers until it reluctantly issued “a crucial permit to fill wetlands on the Xanadu site”.

When Lehman Brothers Inc. filed for Chapter 11 bankruptcy in 2008, they were the fourth-largest investment bank in the United States.

Reports say that the lender, Xanadu Mezz Holdings (I know, I know), left Xanadu $22.9 million USD short after defaulting on a promised $208 million USD loan. Colony Capital and its partners later took XMH to court and sought $1.3 billion USD in damages, only for the presiding judge to rule in favor of the defendant.

Blue laws are somewhat antiquated laws that restrict or outright ban certain activities on Sundays, rooted in the idea that people have a holy obligation to observe the Sabbath. Usually in the United States, restrictions apply to highly specific activities, such as selling alcohol or hunting. Bergen County, New Jersey upholds some of the last remaining blue laws that explicitly ban the sale of goods such as clothing, furniture, and electronics. Because the laws were, in many cases, written long ago, they generally don’t explicitly prohibit modern developments like sports arenas or amusement parks.

In 2023, MrBeast disavowed the MrBeast Burger chain concept, describing the product as ‘disgusting’, ‘revolting’, and ‘inedible’ in a multi-million dollar lawsuit.

For those unfamiliar, the premise of the South Korean Netflix series Squid Game focuses on 456 financially-strapped individuals who participate in a series of children’s games with deadly twists in hopes of winning a large cash prize. Watching a MrBeast-funded recreation of Squid Game in an empty American Dream was definitively the most “perhaps I am experiencing late-stage capitalism in real time” moment of my life thus far.

I wasn’t willing to pay the $59 USD fee to get a closer look at the inactivity.

I don’t have definitive stats backing up that wave pools are among the most dangerous attractions out there, but wave pools seem to be the culprit behind an alarming number of the injuries and deaths listed in the Wikipedia article “List of incidents at independent amusement parks” (and really all of the other related amusement park incident-adjacent pages, for that matter).

(The largest mall in North America)

(The largest mall in the United States)

As opposed to giving as a random act of kindness.

I’m not one to generally align on the side of billionaires, but the Ghermezian family has made philanthropic contributions to dozens of medical, educational, and public service organizations. On the other hand, they did try to sell counterfeit hand sanitizer that may or may not have contained dangerous levels of methanol while facing financial pressure during the height of COVID. I don’t know how to parse all of that.

This hypothetical shopping center has already been nicknamed “Alligator Mall”, which is kinda cute I guess.

This reminds me of what happens with construction projects in China. The project is approved, the money is handed off, the half-constructed building is left in disrepair, and the contractors, having done as little work to justify the funding as possible, drain the project coffers. There are entire ghost towns like this. Great piece, Meghan. Thank you.

As a former Jerseyan as well who has spent countless hours in malls--both when they were thriving decades ago and recently as they decompose in a sad, silent solitude--this was both an excellent read and bittersweet elegy. Thank you for sharing it.