The Great Hobby Lobby Artifact Heist

How an American Evangelical arts and crafts empire managed to loot antiquities en masse from a long-lost Mesopotamian city-state. (Pt. 2 of 2)

Author’s Note: This is Part Two of a two-part series. If you haven’t already, you can read Part One here. Thanks!

From the start, cultural property law expert Patty Gerstenblith sensed something was amiss with the array of tablets and seals laid out in that hotel conference room in Dubai. Though she did not accompany curator Scott Carroll and Hobby Lobby CEO Steve Green to the UAE herself, their account of meeting with three antiquities dealers bore all the hallmarks of something illicit afoot.

The presentation itself was the most readily apparent warning. Smatterings of irreplaceable vestiges were packed loosely into crates and cardboard boxes without protective materials. Other items were arranged in layers on top of one another on the surface of a coffee table. Some were spread out on the floor, hardly treated with the sort of care reserved for things that manage to survive 4,000 years of wear and tear. By all accounts, it was a scene that would make anyone remotely concerned with the conservation of antiquities recoil.

The dealers offered an equally suspicious backstory. None of the men in the conference room claimed to legally own the items offered for sale. Instead, they claimed to represent an absent fourth Israeli party looking to downsize a private family collection. Allegedly, the father of the fourth party legally acquired the tablets and seals from an Israeli market in the late 1960s – conveniently, just before UNESCO enacted international protections to prevent trafficking of cultural property.

The Americans weren’t entirely sure what was being presented to them, nor did they have the faintest idea what the strange inscriptions on the surface of the stone artifacts signified. But the price was right. Though Carroll suspected the haul was worth roughly $12 million, the dealers were willing to part with their goods for just $2 million. Green, the financier of the operation, could hardly pass up such a steal.

Unfortunately, Ms Gerstenblith – hired as a consultant by the Greens upon their return to the United States – suspected that the items were just that. A steal.

Behind closed doors in Oklahoma, she expressed these concerns to her clients. There’s no knowing the exact details of their verbal exchange. However, court documents ultimately released the following excerpt from a memorandum Gerstenblith penned1, directed to the Green family:

“I would regard the acquisition of any artifact likely from Iraq (which could be described as Mesopotamian, Assyrian, Akkadian, Sumerian, Babylonian, Parthian, Sassanian and possibly other historic or cultural terms) as carrying considerable risk. An estimated 200-500,000 objects have been looted from archaeological sites in Iraq since the early 1990s; particularly popular on the market and likely to have been looted are cylinder seals, cuneiform tablets . . . . Any object brought into the US and with Iraq declared as country of origin has a high chance of being detained by US Customs.

Years after the 2010 trip to Dubai, Carroll claimed to have advised Green on two separate occasions to end sale negotiations with the dealers due to “issues of provenance”. To this, Green was said to have simply responded that his family was “not averse to risk”.2

But the “risk” that the tablets and seals were illegally procured and unethically peddled wasn’t so much a risk as it was a near statistical certainty.

At the start of the millennium, Iraq became the epicenter of one of the largest-scale artifact looting incidents in modern history. Second only to the widespread plundering of European art by Nazis (and, following Germany’s defeat, Soviet “trophy brigades”), the full extent of the theft is difficult to estimate with any degree of precision, complicating recovery efforts to this day.

Accounts describing the looting of artifacts from the Levant date back as far as 1160 BCE, when a pre-Iranic people of Elam sacked ancient Babylon. However, the antiquity-rich region were largely overlooked by centuries worth of kings and collectors. Following the Muslim conquest of Persia and the onset of the Islamic Golden Age, the ruins of old cities were considered vestiges of Al-Jāhiliyyah, the age of ignorance. Public interest lay in new scholarly pursuits and discoveries emerging from intellectual hubs like Baghdad. The secrets of a backwards era forgotten were best left with the dead.

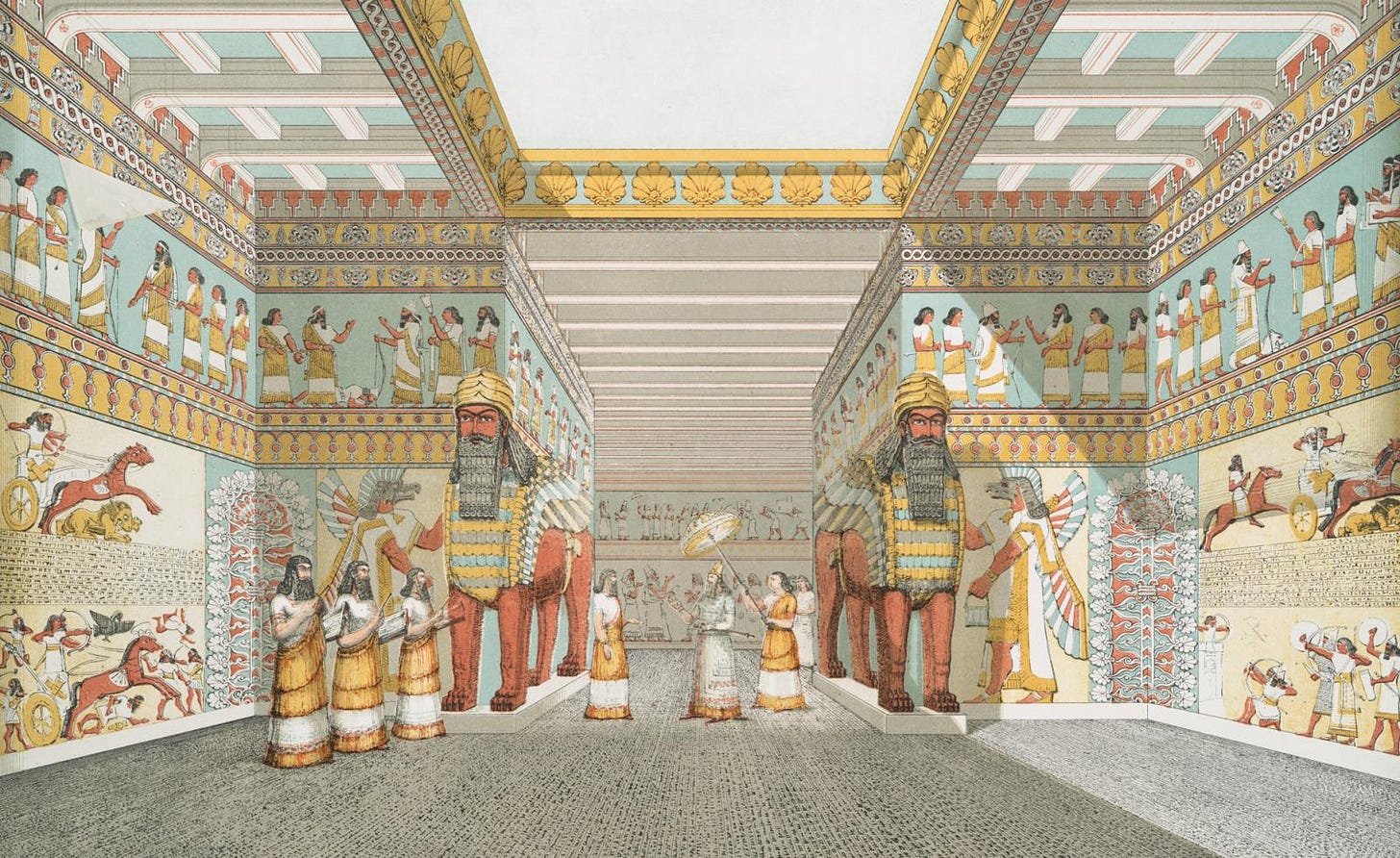

Drastic change came in the mid-19th century, when Western adventurer-archaeologists ventured East and began conducting excavations of their own. They soon brought home spectacular reports of ancient cities rediscovered on the outskirts of Mosul and Baghdad. The unearthing of settlements like Nineveh, the city at the center of the book of Jonah, uncovered texts corroborating the historicity of certain biblical accounts. Remnants unearthed provided glimpses into the lives of the earliest Assyrian Christians. Theologians and churches were astounded and began pouring money into Levantine expeditions with earnest. To such patrons, archaeology became something more than scouring for bones and crumbled structures; it was a means of validating religious truths, long confined to the fallible realm of blind faith.

This newfound interest prompted the Ottoman Empire – then the ruling power over present-day Iraqi territory – to implement rudimentary antiquity laws, primarily targeting the efforts of Western archaeologists. Some rulers were lenient in enforcing such policies, and a small trickle of looted Iraqi goods continued to make their way to black market vendors3.

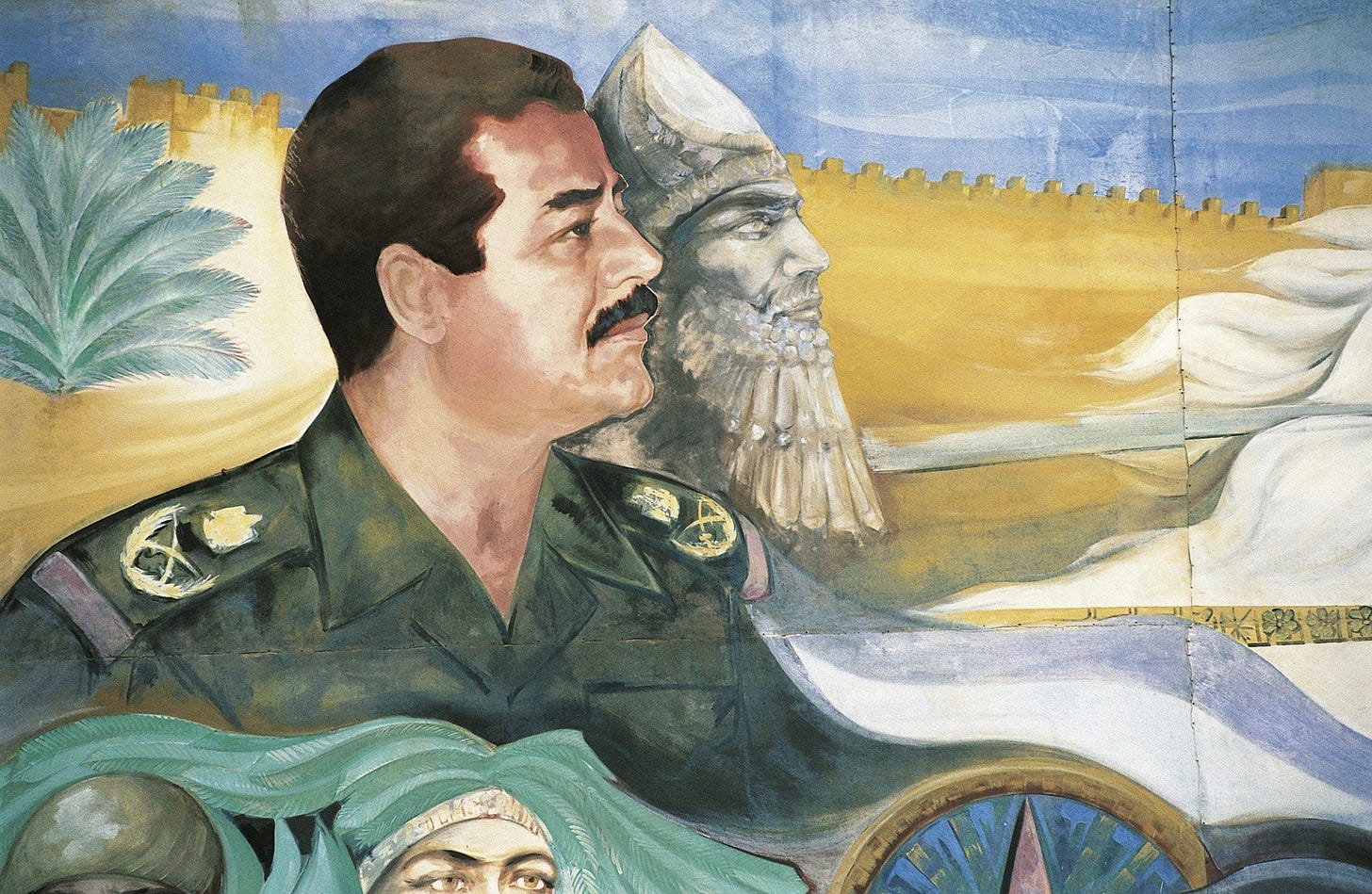

But the rise of a Ba’athist police state led by Saddam Hussein brought with it severe consequences for pillagers4. Where predecessors saw little more than spent rock, the autocratic regime saw something of value. In their eyes, restoring glory to oft-overlooked Mesopotamian heritage sites was a means of strumming up national pride5.

During his rule, Saddam insisted that his people were the legitimate and rightful heirs to a once-great civilization. He likened himself to Nebuchadnezzar6, the great Babylonian king equally capable of building wonders and destroying nations. Repurposed as propaganda, armed guards were ordered to protect excavation sites. Theft was treated as an act of treason. Smuggling stones to perceived enemies of the state simply ceased to be a worthwhile endeavor.

So, while biblical archeologists and Iraqi citizens alike were well aware that a trove of treasures lay hidden in the tells of Iraq, excavating and exporting such treasures was difficult, if not completely impossible.

But the state struggled following the Gulf War, and priorities shifted. A decade of sanctions led to economic decline so severe that necessities became unaffordable. Infrastructure crumbled. Government resources grew sparse. Most of what could be spared funded military endeavors to maintain the illusion of regime strength. Many of those who continued to safeguard Mesopotamian antiquities did so on a volunteer basis.

When US and UK troops ultimately invaded the nation in 2003, the last remaining policies in place to protect Iraqi artifacts perished within days.

Iraqi troops weren’t preemptively deployed to shield cultural heritage sites – men were far too valuable, and the government feared that wasting any to keep safe the nation’s most valued treasures would be viewed as a sign of weakness, a wavering of confidence in Iraqi ability to hold off foreign invaders. Simultaneously, invading forces didn’t feel as if it was their responsibility to protect such sites. Some rudimentary efforts were made to avoid directly firing at museums and cultural landmarks unfortunate enough to get caught in the thick of battle. But the mission at hand was to swiftly overthrow Hussein’s brutal totalitarian regime. Once the object of their aggression was forced into hiding, soldiers had little interest in acting as police in the vacuum left behind. Even if foreign troops wanted to, the heavy tank units stationed in major cities had little recourse in effectively combating unarmed civilians committing petty crimes in the wake of battle7. They lacked basic crowd control tools like shields or batons, and nonviolent offenses hardly justified the use of the lethal weapons they had on hand8.

Therefore, little was done to actively protect institutions left vulnerable.

This left the task of guarding to the private citizens, primarily those working security at facilities such as the Iraq Museum in Baghdad9. In many cases, the museum staff and archaeologists were the only people standing between the collections and outside danger. Almost all (understandably) fled their posts once troops rolled in and gunfire broke out. Untrained and unequipped, they had few means of defending themselves, let alone the artifacts. Mortal danger loomed for those unwilling to budge. At the Museum of Iraq in Baghdad, for instance, guerrilla soldiers armed with RPGs and machine guns positioned themselves directly on museum grounds.

During battle, invading soldiers generally made quick work of neutralizing immediate threats. But, in their efforts to work as expeditiously as humanly possible, they wasted little time seeking out the next stronghold. This allowed opportunistic looters to follow in their footsteps.

When the gunfire finally ceased, troves of relics were left completely unattended. Free from punishing armed soldiers, the threats of authoritarian megalomaniacs, and the cries of stodgy intellectuals who clung to the past. Most people, whether out of residual fear of repercussion or moral fortitude, stayed clear of the unsupervised valuables. But some10 – enough – saw a small window of opportunity and took what they could.

When the dust settled and staff returned to the Iraq Museum in Baghdad, the institution was stripped of approximately 15,000 items from its collection. Still more were destroyed entirely in the chaotic scramble. Undigitized catalogs were also destroyed, complicating efforts to identify what was missing from the museum. Coverage of the loss was widespread, and news outlets and world leaders alike spoke out (justifiably) in the wake of the humanitarian tragedy.

However, many fail to realize that the theft that took place at the Iraq Museum during the Battle of Baghdad represents just a small percentage of the looting that took place throughout Iraq immediately following the fall of Saddam Hussein.

Over 20,000 pre-Islamic archeological sites are scattered across modern Iraq, most of which are located in rural areas lacking infrastructure. When the bedlam of war erupted, all but the most famous of archeological sites (Ur, Babylon, Nineveh, etc.) were left virtually defenseless for months. When funds began to dwindle before the invasion, it wasn’t the employees of prestigious museums that suffered immediate consequences. Instead, the guards and laborers who worked at largely uncharted ruins far from the eyes of administrators in Mosul and Baghdad were the first to suffer pay cuts and job loss. When international aid finally arrived, it was directed solely toward recovering the ransacked museums of major cities. Securing lesser-known, at-risk sites was simply not seen as a priority.

It soon became clear that no cavalry was coming to the rescue. Intruders could act at unsecured archeological sites with little risk of impunity. Rumors began to circulate in some areas that a fatwa had been issued allowing for the looting and sale of pre-Islamic antiquities. Perhaps people’s willingness to believe was fueled by wishful thinking. In areas where most struggled to get by, these archeological sites were essentially gold mines, loaded with buried treasures for those willing to pick up a shovel and dig.

In a matter of weeks, industrial-scale looting operations came to fruition.

Unarmed, unpaid men soon found that protecting these archeological sites was futile. Teams of men – neighbors, sometimes – carried guns and demanded entrance. Numerous teams were even led by former members of the State Board of Antiquities, trained to recognize potentially valuable items. Opportunistic villagers did much of the backbreaking labor. At some sites, such as Umma, electrical generators were brought in to facilitate digs through the night. Upon finding an item, workers would sell directly to on-site middlemen for as much as several hundred dollars11. From there, the middlemen would sell finds at steep upcharges at village bazaars. If they were particularly well-connected, these middlement might peddle wares to royal families and wealthy private collectors.

Like the Greens.

These operations persisted for approximately two years, after which a specialized archeological protection service was finally deployed to protect Iraq’s lesser-known ruins. By then, many sites were decimated entirely, reduced to trenches and the shards of antiquities shattered in the frantic rush to find a fortune. Experts believe that 400,000-600,000 artifacts in total were looted from Iraqi archeological grounds between 2003 and 2005.

All this is to say that Patty Gerstenblith was not at all off base when she advised the Green family to steer clear of the incredibly suspicious artifacts presented by the incredibly suspicious men present in that hotel conference room in Dubai.

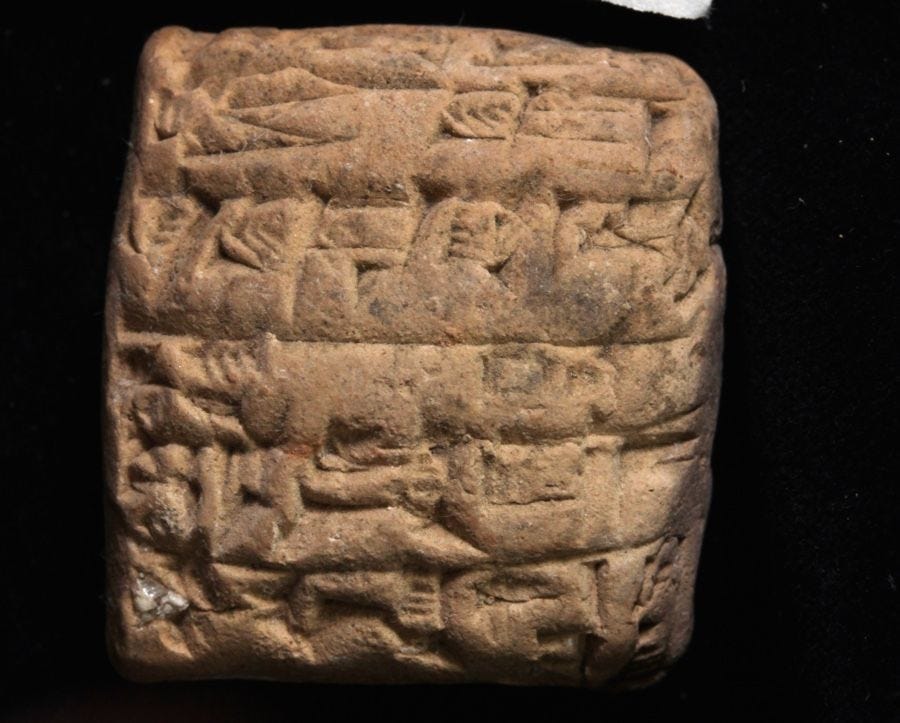

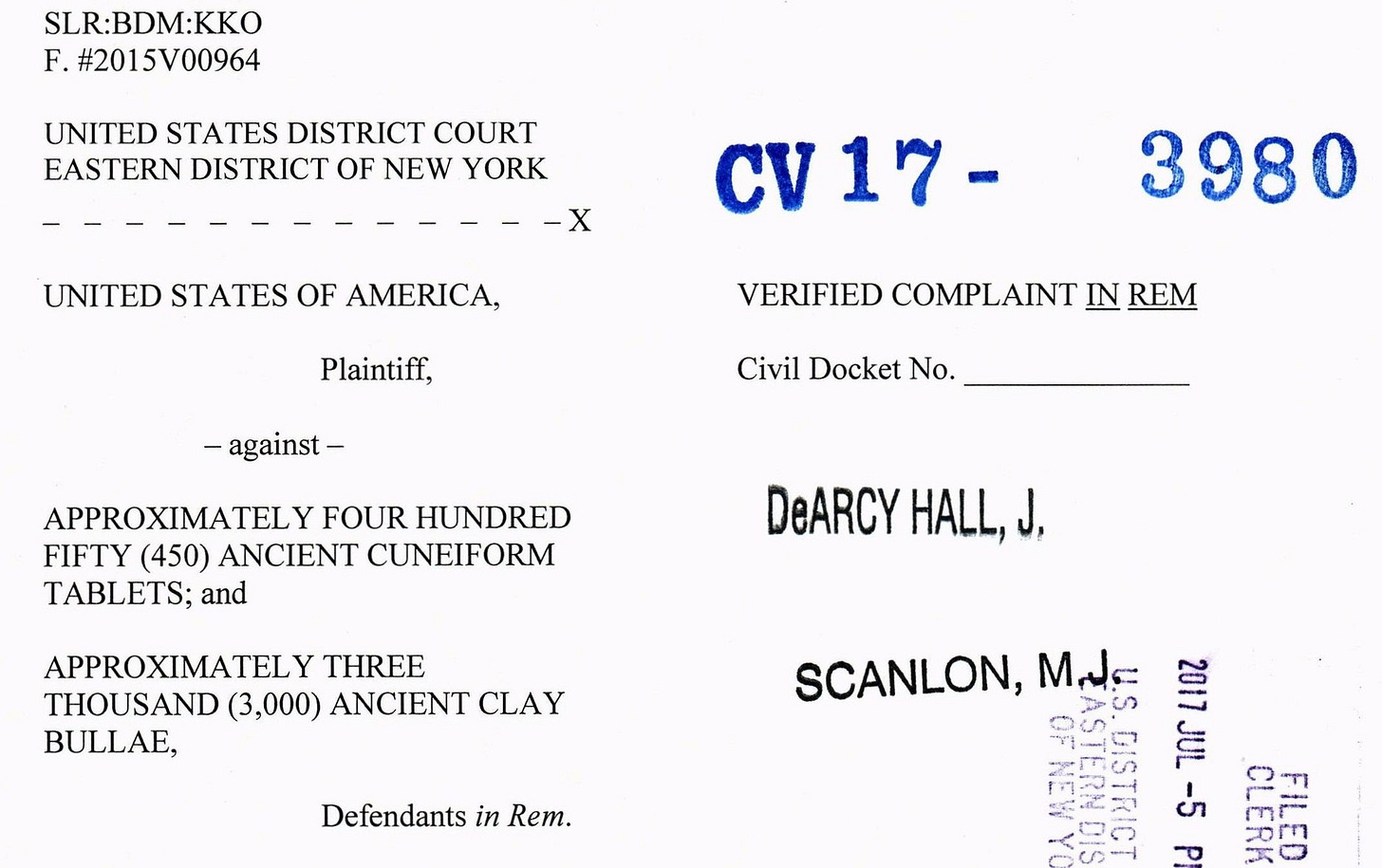

Nevertheless, Hobby Lobby proceeded to purchase approximately 450 ancient cuneiform tablets and approximately 3000 clay bullae12. The drafted provenance statement claimed that the lot was purchased for $1.6 million from the mysterious fourth dealer, whom Green and Carroll never met or directly contacted. Once the documents were signed, the money was wired to seven personal bank accounts, none of which were connected to the supposed Israeli seller.

Allegedly, Gerstenblith’s expert memorandum was never shared with Green, Carroll, the dealers, or anyone involved with the purchase of the items (though she presumably verbalized similar concerns while meeting in-house). At a glance, this is a strange oversight. After all, the Greens specifically hired Gerstenblith for consultation on the legality of the transaction.

It only begins to make sense when you realize that the legality of the situation never had a bearing on whether or not the purchase would take place. Rather, they sought to understand the exact laws they’d have to skirt to get what they wanted.

Normally, Hobby Lobby would turn to its International Department to sort out the logistics of importing. The department primarily focused on bringing in products to be sold in Hobby Lobby stores. But upon the establishment of the Green Collection, the team pivoted and began to coordinate the transport of antiquities as well. Normally, the International Department collaborated with a customs broker to ensure the smooth and legal passage of valuable shipments.

In this case, going through these pre-established channels wasn’t in Green’s best interest. A custom broker pre-emptively informed Hobby Lobby associates that such a large and unusual shipment would likely be searched and seized at the border. The importation of Iraqi cultural property has been heavily restricted in the United States since 1990. This particular restriction also encompasses “items with respect to which reasonable suspicion exists”. Even if Green feigned ignorance, he’d still be committing a crime because reasonable suspicion was evident. A flimsy provenance statement claiming origins from an unseen family collection accrued in the 1960s13, signed by a dealer the Greens never bothered to speak with, would hardly serve as a shield from legal consequences should they be caught.

So, a scheme was devised to ensure the contraband wouldn’t be caught.

When a shipment goes through US Customs, the sender must attach a description of the contents being shipped. Alongside this description, the sender must also include an invoice or estimate value of the contents in question. Customs and Border Protection (hereafter referred to as CBP) then uses this information to assess whether the shipment will undergo a formal or informal inspection.

Generally, shipments exceeding $2000 in value are subject to more scrutinous formal examinations, which may or may not include x-ray scans and/or physically sifting through the contents of a shipment. However, items falling under the $2000 threshold – generally personal items and innocuous gifts – often receive little more than a passing glance before gaining clearance to continue across the border. To thoroughly examine every item that enters CBP simply wouldn’t be feasible, considering the sheer volume of shipments that pass through each day. While low-value packages aren’t completely unmonitored, they are far more likely to make it through CBP unprobed. Aside from the occasional spot-check, smaller items tend to demand attention only when attached to suspect documentation.

The entire collection Hobby Lobby sought to bring to Oklahoma City far exceeded $2,000 in value and would have likely warranted a formal inspection. This would be bad, because any degree of investigation would instantly reveal that something illegal was afoot.

So, an unnamed curator (likely Scott Carroll, given his authority, experience, and established involvement with the acquisition) worked directly with the dealers to make the artifacts less conspicuous. The tablets and seals were split into much smaller lots that could, conceivably, fall below the $2,000 threshold. Newly drafted fraudulent invoices reflected this. According to CBP documentation, each package (containing anywhere from 12-300 irreplacable Mesopotamian antiquities) was said to be valued at approximately $300. Descriptions were fudged to further misrepresent the true contents of each lot and avoid detection from authorities; shipments of tablets were labeled as “ceramic tile” samples on multiple occasions.

For good measure, countries of origin were inaccurately listed as Israel and Turkey in hopes of throwing authorities off the scent of the crime. Packages were shipped between three Oklahoma City locations corresponding to Hobby Lobby HQ, Mardel’s Inc. HQ14, and a Hobby Lobby affiliate known simply as Crafts, Etc.! The invoices attached to shipments forwarded to Mardel Inc. and Crafts, Etc.! falsely indicated that the contents were sold directly to the corresponding company via a dealer in the UAE, contradicting the original provenance statement.

If this seems difficult to follow, it’s because it’s meant to be. But these inconsistencies, convoluted as they are, are crucial to note. They illustrate that Hobby Lobby’s actions are not borne of a newcomer’s ignorance or an administrative error. They are instead indicative of an extensive, premeditated pattern, intentionally devised by people knowingly perpetrating something deeply wrong.

And it almost worked. Between December 2010 and January 2011, hundreds of cuneiform tablets and over a thousand seals were express-shipped across eight packages sent from both the UAE and Israel. These packages passed through JFK’s international mail facility entirely undetected and arrived in Oklahoma City without incident. An additional three made it through an international mail facility in Memphis, TN.

But on January 3, 2011, a package said to contain fifty “handmade clay tiles”, priced at $5 a piece, was flagged for inspection by CBP for unspecified reasons. Officers instead found and seized fifty small cuneiform tablets. Over the next two days, four additional packages from the same sender were flagged in Memphis. They, too, were filled with mislabeled antiquities. In total, 223 cuneiform tablets and 300 clay bullae were confiscated.

Hobby Lobby was notified of the seizure in March, though they likely realized something was amiss when the packages failed to arrive. In an attempt to reclaim the artifacts, Hobby Lobby filed a petition attached with a new provenance statement, conveniently accounting only for the seized items15. The development of a full-fledged CBP investigation did little to discourage the Green’s mission in the meantime. Hobby Lobby was so confident in its ability to evade consequences that, in September 2011, months after being caught red-handed with contraband, they arranged for the illicit dealers to illegally ship another 1,000 clay bullae to the US.

Around the time of this final shipment, plans to develop a biblically-themed museum to house the Green Collection finally solidified. Though the initial plan was to build in Texas, the Greens eventually found an irresistible deal in the heart of Washington DC. Just two blocks from the National Mall, snug in the center of the nation’s political powerhouses, a defunct refrigerating warehouse was deemed worthy enough to serve a greater purpose. The sale was finalized in 2012, and construction began on what was to become the Museum of the Bible (MoB). The Green family poured hundreds of millions of dollars into the facility itself16, intent on creating an all-American religious spectacle capable of outshining the towering gilded medieval cathedrals built on the tithes of European peasants. It was to be the sort of institution so awe-inspiring, it inspires belief in higher powers.

Plans went into effect to build a grand hall, filled with Jerusalem stone beneath a 140-foot-long LED display screen ceiling. Plants were shipped in from the Levant to create a biblically accurate “Garden of Eden” rooftop solarium. Board members and administrative staff were hired to oversee the museum and collection, allegedly none the wiser17 that CBP was actively investigating potential mass smuggling. Even dogged by allegations of hoarding wartime plunder by US authorities, a wholeheartedly unconcerned Hobby Lobby conducted business as usual.

And with good reason. Six years would pass before anyone, aside from investigating agents and top Hobby Lobby leadership, would learn that anything was amiss with the Green Collection. Steve Green would later claim that he never felt the need to share details of the CBP case with Museum of the Bible leadership, as he considered the provenance discrepancy to be an “internal Hobby Lobby matter.”

And, technically, intertwined as the entities may be, Steve Green wasn’t wrong. Hobby Lobby and the Greens are inextricable. Though the MoB showcase is composed almost entirely of donations from the Green Collection, curated to fit a Green-approved narrative, the Green Collection itself is privately owned by the family. And while the Greens are ever-eager to rake in the lucrative tax write-offs generated by the donation of collection pieces to the MoB and beyond18, huge swaths of their extensive collection of artifacts remained stockpiled. The tablets and seals at the center of the CPB investigation were among those untold numbers that were never donated, never translated, and never truly valued. Once flagged for investigation, they became too hot to handle – useless to reputable scholars with ethical objections, unsellable to anyone working in good faith. They certainly couldn’t be displayed in the new museum and draw immediate controversy. “It’s like a used-uranium dump,” wrote Robert Cargill of the Biblical Archeology Review. “It just sits there in the dark and glows.”

Perhaps the Greens believed they could shake off the scandal entirely, or at least avoid public backlash. But, in the summer of 2017 – just a few months before the slated grand opening of the MoB – the US government formally filed a civil forfeiture action against Hobby Lobby.

Approximately 5,500 items were seized from the Green Collection as a result. 3,800 of the items confiscated were ultimately returned to Iraq, according to a 2018 ICE press release.

The US Department of Justice further issued Hobby Lobby a $3 million fine as punishment for its lack of due diligence. Considering the scale of the operation and the Green family’s immense fortune, this penalty amounted to little more than a slap on the wrist.

Nevertheless, the billionaires appeared remorseful when word of the misconduct reached mainstream media outlets. “[Hobby Lobby] was new to the world of acquiring these items, and did not fully appreciate the complexities of the acquisitions process,” reads an official statement Hobby Lobby issued in the aftermath. “This resulted in some regrettable mistakes. [Hobby Lobby] imprudently relied on dealers and shippers who, in hindsight, did not understand the correct way to document and ship these items.” Steve Green himself admitted some degree of fault; in 2020, he told the Wall Street Journal that “criticism of the museum resulting from my mistakes was justified”.

Despite the controversy, the Museum of the Bible opened as scheduled and has since amassed widespread praise. One NYU Jewish studies professor called the museum a “monument to interfaith cooperation”, echoing a common sentiment that the facility’s primary focus is to educate rather than evangelize. Thousands of reviews, amateur or otherwise, repeatedly commend the museum’s interactive exhibitions as profound and inspiring.

Promises of higher provenance standards going forward have lent further credence to the future intentions of MoB, and by extension, the Green Collection19. MoB implemented special updated acquisition policies pertaining to items acquired before 2016, claiming to have invested “significant resources” into provenance research. Furthermore, in May 2020, Steve Green relinquished an additional 13,000 privately owned antiquities of unverifiable provenance to the governments of Egypt and Iraq. Against all odds, both Green and MoB have since been praised as “setting an example for responsible ownership of foreign cultural heritage”. Though Scott Carroll was never faced with prosecution for his pivotal role in the Iraqi artifact scandal, he has since become something of a scapegoat for previous Hobby Lobby mishandlings. Though it’s unclear whether he was fired or resigned, a multitude of sources are quick to point out that Carroll parted ways with MoB and the Greens back in May 2012. The implication is often that his departure was an act of cutting out the cancer within the organization.

For most, these actions represent signs of true contrition. Despite the massive number of illegal objects found in Hobby Lobby’s possession, many have chosen to forgive and forget. So much so that the MoB and the Green family have managed to skirt significant criticism concerning a slew of provenance and authenticity issues that have emerged since the Iraqi artifact scandal.

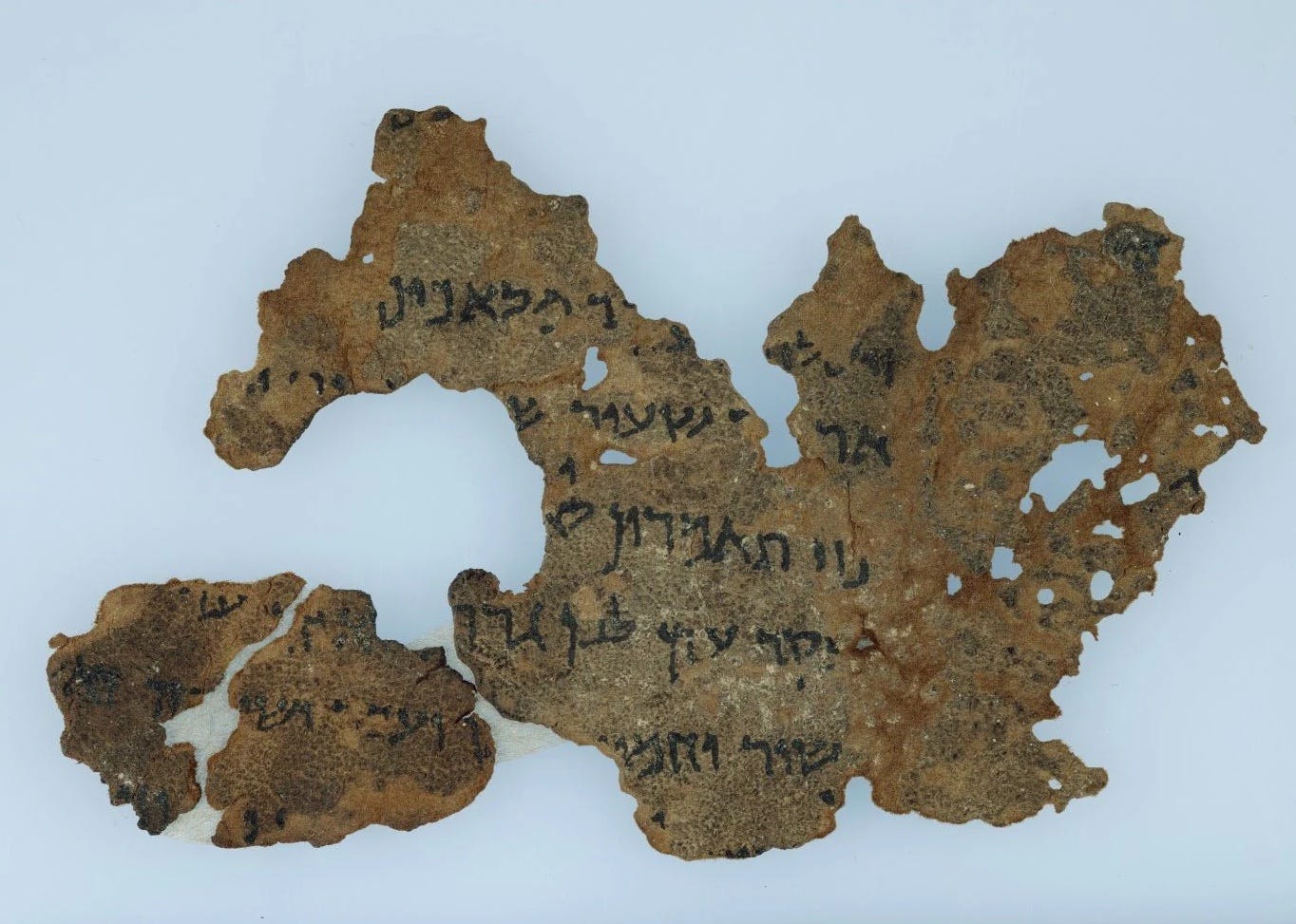

In 2020, experts revealed that 16 purported Dead Sea Scroll fragments on display at MoB were twentieth-century forgeries. Though the forgeries themselves were convincing enough to warrant an “exhaustive” review, post-mortem findings revealed that the scrolls were purchased with little to no regard for provenance. Several were obtained as late as 2014 – years after the trouble with the looted Iraqi pieces began, years after Carroll parted ways with the Greens.

The next year, in 2021, it was alleged that Oxford scholar Dirk Obbink had stolen at least 32 New Testament papyrus fragments from the Egypt Exploration Society, then proceeded to sell the stolen goods to Hobby Lobby. This included verses from the Gospel of Mark erroniously claimed to date back to the first century. In addition, Hobby Lobby obtained approximately 20 uncataloged Egyptian death masks from Obbink, who labeled the works “suitable for dismantling/dissolving”. Rather than verify the provenance of the items for sale, they simply trusted the crooked scholar’s claims that the remarkable relics had suddenly surfaced from a “private family collection”.

Most recently, the Museum drew tepid criticism in September 2024, when a five-by-five-inch Jewish prayer book dating back to approximately 700 CE was debuted. The book in question, believed to be the oldest bound Hebrew work, was found in a Bamiyan Valley cave by an Afghan insurgent group and subsequently smuggled out of the war-torn country. Though MoB now retains legal custodianship of the book due to obvious humanitarian concerns2021, it spent years in the Green Collection untouched, inaccurately dated and labeled as originating from a synagogue in Cairo. The flub was only discovered when a MoB curator stumbled across an image of the manuscript, identified as Afghani, by chance while browsing fucking Google Images. Were it not for this incredible stroke of luck, the book would almost certainly remain divorced from its cultural heritage and historical significance22, collecting dust indefinitely.

It’s not as if issues of provenance are unique to the MoB and the larger Green collection. Respected institutions, such as the Metropolitan Museum of Art, have likewise been caught with questionable works procured without reputable provenance. Switzerland’s largest art museum proudly hangs Impressionist paintings sourced from the contentious collection of a Nazi arms dealer. Christie’s Auction House knowingly obscured the provenance of a cuneiform tablet detailing a scene from the Epic of Gilgamesh and proceeded to sell it directly to the MoB, going so far as to hand deliver the relic to Oklahoma to avoid state sales taxes.

Blame for what is clearly a systemic issue cannot be placed squarely on the shoulders of Hobby Lobby. Their accomplices are numerous, and they’ve taken steps to return items undeniably stolen.

But would those steps still be taken had not some nameless CBP agent decided to examine a box of "ceramic tile” sample at a mail facility in Memphis nearly 15 years ago? How many dodgy packages addressed to Oklahoma City made it through authorities undetected, destined to sit in some undisclosed storage facility? Is an apology still valid if it only comes after you’ve been caught? Is a lesson truly learned if the same infraction occurs again and again and again?

Steve Green has repeatedly described himself as a “storyteller”, first and foremost. Not a business mogul. Not an art collector. Not even a Christian. But a man intent and controlling and disseminating a narrative, bent on reframing knowledge and culture in a way that fits a particular worldview. Immune to true penalization, it’s unlikely that there will ever be a satisfying comeuppance for the Green family. Justice was served, but only in the most technical sense. Countless financial contributions in the form of $24.99 Hobby Lobby John 3:16 wall decor purchases continue to fuel the Green’s agenda. Questions linger without answers.

But one thing worthwhile did emerge from the case of the 5,000 smuggled Iraqi antiquities seized by the CPB. Shortly before shipping the items back to Western Asia, archaeologist and cuneiform scholar Eckart Frahm was given approximately two and a half days to determine what, exactly, the United States would be returning to Iraq. Once repatriated, the items would enter a substantial queue of thousands of unidentified looted artifacts, inaccessible to scholars for the indefinite future.

It was only when Frahm arrived that an attempt was made to decipher the story the stones sought to tell. No longer were they viewed as tools to be wedged into tales woven around political ideology or religious dogma. For the first time in a long time, someone tried to read the forgotten language etched into the clay and buried in the dirt.

Within those two-and-a-half days, Frahm discovered that the artifacts he had in his hands originated from Irisagrig. It remains uncertain which previously unexcavated, ransacked tell looters extracted the tablets and seals from. There’s a real possibility that the former grounds of Irisagrig remain forever lost.

Ironically, the words had little to do with religion at all. Instead, the tablets were largely found to be legal documents from a local government archive. They told of envoys tasked with the construction and upkeep of roads and canals. There were accounts of royalty visiting the city’s palace. Records showed the dogs were well-fed, and that even the lowliest of workers received meat rations.

Irisagrig may be something never fully understood, buried deep beneath dirt. But if a silver lining is to be found, it’s this: amid a 21st-century scandal embroiled in war crime and evangelism, the lingering memories of a people long left behind were resurrected. They prospered, and none of them went hungry.

Perhaps divinity lies in something as simple as that.

If you enjoyed this essay and want to say thanks, please consider buying me a coffee 😎

Hobby Lobby lawyers later told federal investigators they never shared Ms. Gerstenblith’s letter with the Greens.

It is possible that Carroll’s claims were made in an attempt to shirk culpability in the whole messy affair to come. But, for what it’s worth, the Greens have not refuted Carroll’s version of events.

For instance, 19th-century Ottoman sultan Abdul Hamid II saw little use for antiquities save for those crafted from valuable materials like gold. “Look at these stupid foreigners!” the sultan once exclaimed, “I pacify them with broken stones.” Ironically, he believed that he was exploiting Westerners through the sale of antiquities he viewed as worthless.

Perhaps unsurprisingly, it was during his reign that a German archeological team managed to smuggle the entire Ishtar Gate by hauling crates full of bricks to Europe. The Gate was then reconstructed in Berlin, where it remains today.

As Lawrence Rothfield writes in the 2009 book The Rape of Mesopotamia: “Saddam tried to curb the looting with draconian measures, including staging a televised execution of ten wealthy businessmen from Mosul who had chopped a winged Assyrian bull in pieces and tried to smuggle it into Jordan”

To be fair, this strategy of elevating the ancient past to mythical greatness to promote nationalism is not unique to Saddam. In the first half of the 20th century, Mussolini prioritized numerous initiatives aimed at preserving and restoring ancient Roman antiquities for similar political reasons. Hafez al-Assad of Syria and Moammar Gadhafi of Libya, both of whom rose to power around the same time as Saddam, also turned to archeological heritage as a means of promoting a shared cultural identity.

Saddam’s interest in Nebuchadnezzar bordered on obsession. A 2003 essay penned by historian Eric H. Cline recounts the following:

“Although Nebuchadnezzar was neither Arab nor Muslim, Saddam Hussein’s “Nebuchadnezzar Imperial Complex,” as one psychologist called it, has been remarkably consistent. In the late 1980s, he promoted the Iraqi Arts Festival called “From Nebuchadnezzar to Saddam Hussein.” He also had a replica of Nebuchadnezzar’s war chariot built and had himself photographed standing in it. He ordered images of himself and Nebuchadnezzar beamed, side by side, into the night sky over Baghdad as part of a laser light show.”

Soldiers were given specific instructions that, if required to fire a weapon, they “must [f]ire only aimed shots. NO WARNING SHOTS.” Some troops surely must have cared about protecting Iraq’s cultural heritage; however, trying to stop any looting they may have witnessed could have easily escalated into a deadly confrontation.

In the days following the invasion of Baghdad, US military officials claimed that they “didn’t anticipate looting”, though esteemed archeologist and Iraq Museum head Dr. Donny George tried desperately to garner help from American troops. US Defence Secretary Donald Rumsfeld infamously brushed off subsequent criticism for this decision, stating, ”stuff happens”.

Some Iraqi civilians were willing to protect Iraqi museums under siege, but found themselves quickly overwhelmed. In The Rape of Mesopotamia, archeologist Zainab Bahrani describes the efforts of a seventy-something year old guard’s attempt to deter looters in April 2003, equipped only with a walking stick to beat off intruders

An April 2003 article from The Guardian describing the looting of the Nineveh International Hotel in Mosul, though not perfectly analogous, provides some additional insight into the mindset of the individuals who partook in widespread looting:

“Most ordinary Iraqis were too scruffy to venture inside, let alone afford its £16-a-night rooms. Yesterday, they removed all the hotel's bedding and furniture instead. "It is our money. It is our money," 17-year-old Hassan Ali explained. “This hotel has been built with money from Iraq's oil. The oil belongs to us. That's why we are looting.’“

Considering the average Iraqi’s monthly income was around $255 USD at the time, it’s easy to understand how one might set aside reservations to participate in a dig.

A bullae is defined by Encyclopædia Iranica as “sealings, usually of clay or bitumen, on which were impressed the marks of seals showing ownership or witness to whatever was attached to the sealing.”

Even if this family collection was indeed real, it would still violate Iraq’s antiquities laws, which state that “antiquities found in Iraq, whether movable or immovable, on or under the ground, are considered property of the state”. In this case, “antiquities” encompass movable possessions which were made, produced, sculpted, written or drawn by man and which are at least 200 years old. But realistically, no one involved in this story had, at any point, concerns about breaking Iraqi laws.

Mardel is a chain of Christian book stores founded and headed by David Green’s eldest son, Mart Green. It is headquartered quite literally across the street from Hobby Lobby HQ.

In the new provenance statement, the items that had already made it to Oklahoma weren’t mentioned, nor were the items that the dealers had not yet attempted to ship to the United States.

On behalf of the MoB board, Vice Chairman Robert Cooley was quoted to have felt “shortchanged of the facts” upon discovery of the six-year smuggling investigation.

Outside of MoB, the Green family has also donated artifacts to attractions such as Williamstown, KY’s Ark Encounter, which is a pseudoscientific Creationist theme park showcasing a life-size replica of Noah’s Ark from the Book of Genesis. The Greens also loan pieces to (primarily Christian) universities for analysis via the Green Scholars Initiative (though student researchers and mentors are required to sign non-disclosure agreements in regards to any potential findings).

In 2016, the Green Collection was rechristened the Museum Collection, a name so nefariously vague that it makes finding up-to-date information post-scandal next to impossible via a simple search engine query. For clarity’s sake, I’m going to continue to call it the Green Collection.

Tova Moradi, thought to be the last Jew living in Afghanistan, fled the country in October 2021.

Rather than hand the book directly over to surviving Afghan Jews, who have largely relocated to the United States and Israel, the museum has announced plans to provide the Jewish community with “a high-quality replica”.

The discovery of the prayer book established evidence that Jews had settled in Afghanistan and along the Silk Road far earlier than previously believed by historians