The Shifting State of Xiaohongshu

The story of a Chinese "lifestyle bible" that unexpectedly became stomping grounds for a slew Americans seeking digital refuge.

A very special thanks to Afra Wang (of Concurrent) and Tianyu Fang (of Chaoyang Traphouse) for their invaluable insight in writing this article!

Over the past several months, I’ve been unable to get my mind off a 90-second vlog that passed through my periphery by chance. It plays out as follows:

The morning sun shines brightly in the reflection of a glass door, a great ball of radiant warmth. A faceless woman flaunts her outfit of the day – a dark blue dress that falls just above the knee, a lavender quilted coat, and long black socks that hug her slender calves. It’s cute, the sort of outfit a person can only comfortably wear a few days out of the year, during the fleeting transition of seasons. The woman proceeds to top up a prepaid card with a $50 bill before hopping onto some unspecified form of public transit. She makes her way to a department store, where racks of clothing and Louis Vuitton bags hang in perfect, sterile stillness. There are no other shoppers in sight. After browsing the aisles, she treats herself to lunch. Starting with a giant slab of fried chicken breast, the main course is a heaping bowl of soba noodles, complete with all of the fixings one could desire and a can of cola. Along the side, three packets of ketchup rest – one brandishing McDonald’s world-famous golden arches, the other two bearing the instantly recognizable portrait of KFC’s Colonel Sanders.

Each 5-10-second vignette is unremarkable, the sort of stuff you’d find in a trillion other “day in the life” inspired vlogs. Nevertheless, dozens of viewers openly doubt the authenticity of these events in the comment section. “This account gives me a strange feeling,” one user bluntly states. “As if it’s not operated by a real person”.

The doubt almost certainly stems from the fact that this particular vlog, hosted on Chinese social network Xiaohongshu (小红书)1, purportedly documents the experiences of a Chinese exchange student living and studying in North Korea, a country notorious for its strict control of ingoing and outgoing media.

The sheer banality of the vlog is what’s mesmerizing, veracity of its contents aside.

It is unlike any media that I’ve encountered said to come from the mysterious ‘hermit kingdom’. There are no grand, unmistakable gestures of nationalistic pride held among polished buildings with a touch of Soviet flair. No countrymen laugh, cry, sing, or dance in perfect unison2. Conversely, there are no glimpses of malnourished farmers tending the barren countryside captured with shaky hidden cameras. There are no solemn instrumentals tinged with despair, no English voiceovers insisting that the place I’m seeing is a strange and treacherous one.

This vlog stands in stark contrast. It shows something almost neutral, almost normal.

Almost.

My eye consistently gravitates to those stupid little ketchup packets, defiantly flaunting the logos of American fast-food giants. Their presence is puzzling. There are no McDonald’s or KFC franchises in North Korea. They represent aggressive global capitalism and shameless consumerism – qualities that the current North Korean regime is said to find abhorrent. How did Colonel Sanders make his way into this transmission, given the tightly controlled nature of image and ideology allowed to pass beyond the nation’s borders?

The way I see it, there are two possible explanations:

Despite the clear, obstinate branding, the inclusion of the ketchup packets was intentional. Perhaps the creator of the vlog wanted to illustrate that North Korea has all of the small luxuries that developed countries take for granted.

The branded ketchup packets were overlooked entirely, considered a detail so unimportant that it wasn’t worth oversight. This implies that North Korean regulations surrounding imported goods and exported media are not quite as stringent as I’ve been led to believe.

Both options are intriguing. Perhaps if I were a richer and braver and bolder person, I’d travel to North Korea myself, order up a fried chicken breast, and see for myself what gets served on the side.

Instead, I’ve inexplicably found myself delving deeper into Xiaohongshu, the platform on which I initially encountered the uniquely confounding clip and the debate surrounding its authenticity. Though it may not hold the precise answers to the vlog that’s haunted me, my pursuit is driven by the same curiosity, the same irrational longing – obligation, maybe – to try to understand the corners of the world that I may never see firsthand.

As an American, the mere act of logging on to Xiaohongshu feels taboo, perhaps a touch treasonous. The word xiaohongshu (小红书) quite literally translates to “little red book”, a phrase that immediately evokes memories of harsh sociopolitical purges that took place in decades past. For obvious reasons, the app is branded as RedNote3 internationally.

But before it was Xiaohongshu or RedNote, it was simply “Hong Kong Shopping Guide”.

Upon launch in 2013, Hong Kong Shopping Guide was meant to serve as a travel guide for Chinese shoppers, local and abroad. In one comprehensive platform, consumers could share where to find the best restaurants, how to get to the most picturesque landmarks, and (of course) what to shop for at any given locale4. User-submitted videos and reviews would shepherd travellers through sprawling cities such as Shanghai, Singapore, or Seoul with little more than a simple query.

Over the last twelve years, it has morphed into something entirely more complex.

Though Xiaohongshu is frequently compared to TikTok by Western outlets, it is in practice significantly different from Douyin, China’s actual TikTok equivalent. Digital culture writer and researcher Tianyu Fang told me that he first joined Xiaohongshu seeking grocery store recommendations, hoping to find a place in San Francisco that sold his favorite condiments from home. Lately, he’s been using the platform in much the same way he would Instagram. Afra Wang, host of the Chinese-language culture podcast CyberPink, shared that she has used the platform to find answers to the complicated questions that come with immigration. Hundreds of thousands of users living in Chinese diaspora communities offer valuable insight on finding medical specialists and navigating visa issues. It almost acts as a crowdsourced search engine, not entirely unlike Quora.

Since 2023, Xiaohongshu has described itself as a “lifestyle bible”. Today, the social media e-commerce hybrid is populated by over 300 million users and a never-ending stream of content. It is a dynamic space, made to converse and convene as much as to share and influence. The average user is young, educated, and affluent, hailing from Tier-1 cities like Beijing and Shenzhen.

Young women were among the first to flock to the app, given its initial emphasis on shopping. Early adopters found that their most successful posts were those that catered directly to predominantly female audiences. Cosmetic reviews and short-form videos flaunting fashionable outfits thrived. At-home workouts specially designed to mold women to meet traditional Chinese beauty standards garnered billions of views. Strawberries cut into the shape of cats and heavily filtered glamping adventures repelled male users so effectively that the platform initiated advertising campaigns essentially pleading with men5 to join. Though those efforts have been marginally successful, TechCrunch reported in January 2025 that women still account for 79% of monthly active users.

In turn, Xiaohongshu (despite its inherently commercial nature) flourished into a virtual safe space for millions and millions of Chinese women.

Demand in mainland China for women-only physical spaces6, shielded from unwanted male attention and harassment, has grown exponentially over the last few years. There is demand for such places to exist on the internet, too. In practice, creating and policing such a place is difficult, if not impossible. Even so, Xiaohongshu organically grew into something very close. Though far from being a manless cyberspace utopia, Xiaohongshu users frequently refer to each other as jiěmèi (姐妹) – sisters.

Some of this culture of sisterhood is performative, a poorly disguised marketing ploy that uses platitudes of female solidarity as a selling point. But a significant portion of the Xiaohongshu population is composed of women deeply invested in maintaining a space where other women can express themselves. Despite existing in a society with a grounding in patriarchal Confucian tradition and an incredibly complicated relationship with feminism7, it remains a space where women feel empowered.

Amid impending population collapse8, Xiaohongshu is a platform where Chinese women openly weigh the pros and cons of marriage and motherhood. In the center of a culture that sheepishly refers to periods in euphemisms like "例假 (lìjià)" (routine holiday) or "那个 (nà ge)" (that thing) and uses blue in place of red for sanitary product advertising9, Xiaohongshu is a place where decidedly confrontational hashtags like #StopMenstrualShaming spread.

Even as the male demographic has increased and unwanted sexual advances have become more commonplace in comment sections, the women of Xiaohongshu continue to carve out spaces free of men, safeguarded by a whisper network of wordplay. A few years ago, the tag “bǎobǎo fǔshí” (宝宝辅食) – “BabySolidFood” – was used to stave off the amorous advances of men unlikely to venture into the depths of parenting subcommunities. Similarly, lesbian users gather together under the tag “tōngxùnlù” (女通讯录) – “address book” – because the word shares the same initials as “tóngxìngliàn” (女同性恋) – “homosexuality”. There, you can find dozens of cutesy AI-generated pixel art featuring intimate images of quiet moments, meticulously tweaked to resemble real-life same-sex couples hesitant to post photos.

These corners can be difficult to locate, but beautiful upon arrival.

I was fortunate to witness this welcoming, surprisingly open atmosphere – the one that allows countless women to feel at ease – firsthand in January 2025. At the time, a massive, unanticipated flood of American netizens were driven to Xiaohongshu, spurred by concerns that they would soon lose access to TikTok.

Since 2020, US politicians have expressed bipartisan concern over potential security threats posed by TikTok and its Chinese parent company, ByteDance. Fears of data surveillance and covert influence operations quietly simmered as shut-in Americans doomscrolled. These fears ultimately culminated in an executive order instructing ByteDance to divest from TikTok or risk banishment. Following a brief moment of panic, a court injunction quickly blocked the order, which was reversed entirely the following year.

But talk of a ban resurfaced following the creation and passage of the Protecting Americans from Foreign Adversary Controlled Application Act (PAFACA) in 2024. Granting the power to ban any application controlled by a country deemed by the US president as “adversarial”, uncertainty brewed around the future of the extremely popular short-form video hosting platform. The law, explicitly aimed at ByteDance, was an ultimatum: divest stakes in TikTok to a non-adversarial party, or face total annihilation10. In response, ByteDance (unsuccessfully) challenged the constitutionality of PAFACA. As the divestment deadline loomed and ByteDance refused to budge, some American influencers and audiences preemptively sought a suitable substitute.

Xiaohongshu first entered the conversation by way of black beauty influencers, who were among the first to adopt the hashtag #TikTokRefugee. It was a logical jump for this particular niche – Xiaohongshu is the sort of place where makeup tutorials and cosmetic reviews are plentiful and well-received.

But once it became clear that TikTok might actually become inaccessible, word of Xiaohongshu erupted. Major defining aspects of the platform - its intended function, its prominent role in Chinese e-commerce, its predominantly female user base - were entirely lost in translation. Mainstream media reporting further spread the word of Xiaohongshu without bothering to correct the misconception that it was anything more than a replacement for TikTok. The fact that the platform in question was Chinese-based – normally a deterrent for foreigners – made it all the more appealing to those looking to rebel against PAFACA. What better way could there be to express dissatisfaction with US policy than to embrace an app called Little Red Book?

But it was also something far more significant than a simple act of rebellion.

As a general rule, Western netizens and Chinese netizens do not share the same space due to the latter’s strict censorship policies. Rather than attempt to enforce their standards on the rest of the world, the CCP blocks problematic foreign sites via firewall. Many of the highest-traffic sites worldwide are difficult, if not impossible, to access in China without a VPN. This has led to the development of separate but similar applications, designed to abide by CCP regulations and cater specifically to China’s domestic online ecosystem. Baidu takes the place of Google, Tabao serves the same purpose as Amazon, and Weibo is often compared to Twitter.

Likewise, foreign access to Chinese social networks can be made quite difficult. Some services require a Chinese ID to register an account. Bugs hinder navigation abroad, and many tech companies are unwilling to allocate resources toward a historically limited international market. Why would they, when international users can almost always turn to an infinitely more accessible Western equivalent?

But, unlike other Chinese mainstays, Xiaohongshu was uniquely built to suit the needs of users based outside of mainland China. It has no perfect parallel. American policymakers never accounted for a platform like Xiaohongshu, making it a perfect place for newly ousted digital nomads to settle down for a while.

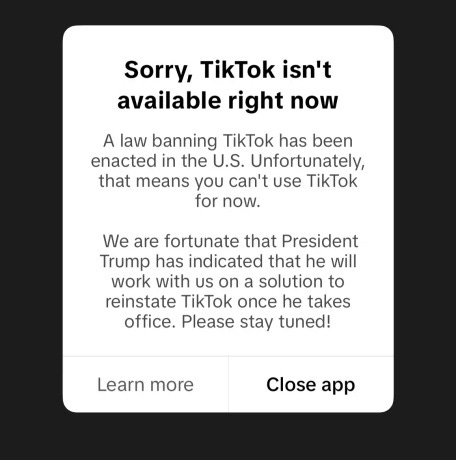

Likewise, Xiaohongshu never anticipated widespread interest among American users to develop without warning. At the beginning of 2025, Xiaohongshu had about 300,000 active users in the United States. That number skyrocketed to 3.4 million users over a single week. Fervor only intensified when, on January 18, ByteDance removed TikTok from US app stores and shut down the platform. Instead of customized feeds of short-form videos, users who attempted to access TikTok were greeted with the following message:

So they arrived in droves, restrictions and language barriers be damned.

And for a few weeks, something truly wonderful and unprecedented took place.

Xiaohongshu recognized that, to retain the surge of foreigners, the platform would have to accommodate their needs as soon as possible. Frantic engineers integrated an AI-powered translator within a matter of days, capable of bridging in seconds the many complex linguistic gaps that have long separated effective cross-communication between Eastern and Western cultures11. Overnight, two groups of people gained the ability to see and understand one another for the very first time.

Reuters described it as “an unexpected bilateral channel for U.S.-China exchanges”. While an accurate description of events, it sterilizes the beauty of it all. Afra Wang described it as something deeply wholesome, “the sweetest moment I've seen in US-China relations in a long time”.

This sentiment seemed to be one shared across the site.

At least, for a short while.

Thoroughly surprised Chinese netizens welcomed their visitors with open arms, offering newcomers advice on how to effectively navigate the platform and abide by its regulations. As Americans expressed a desire to learn Mandarin, bilingual, social media-savvy content creators began churning out videos instructing viewers how to say and pronounce basic words and phrases. Meanwhile, native-English speakers offered Chinese students help with their homework. Travelers from the United States marveled at clips showcasing the greatest feats of cities they’d never heard the names of before, falling head over heels in love with all of China’s most beautiful attributes. And how could they not? Even through an imperfect screen, it’s abundantly clear China is great and beautiful – the physical features of the land itself are striking, and the cities shine bright. The history of its people is rich and storied, and their future is promising.

It was a poignant reminder that, in a world full of chaos and turmoil and uncertainty, the vast majority of us retain an earnest and sincere desire to understand one another. An indicator that advancements in AI might hold in store hope rather than looming existential threat.

But, as with most magnificent things, it was fleeting.

Ultimately, the TikTok shutdown was brief, lasting just over 12 hours. Though ByteDance has not yet met the requirements laid out by PAFACA, President Trump has thus far extended the period of non-enforcement three consecutive times. For many, the novelty of Xiaohongshu wore off. Even many of those who instigated the migration have since returned to the familiar pastures of TikTok.

Perhaps it’s best that the connection was largely short-lived. PR Consultant Hu Wenjing described the phenomenon to KrAsia as a “brief honeymoon period between cultures,” predicting that conflicting values and cultural tensions would inevitably drive netizens apart. As a lay observer, it seems that the summit dispersed long before true squabbling could begin.

Furthermore, the return of Westerners to TikTok has averted a logistical nightmare for Xiaohongshu. Implementing basic AI translation features in under a week was a tremendous (though not altogether impossible) undertaking. Executing comprehensive English language moderation would be a separate beast entirely. The platform never anticipated significant usage outside of the Chinese-speaking population and was ill-prepared to handle large volumes of foreign-language rhetoric that crossed the boundaries of the CCP’s stringent censorship policies. In January, a mad scramble ensued to outsource moderators for “English video content on RedNote." Guo Jiaku, writing for PCOnline Pacific Technology, described the incoming Western traffic as “the sword of Damocles hanging over Xiaohongshu’s head”:

Simply put, foreign netizens who download and use Xiaohongshu in the app store are riding the same wave as domestic netizens. This means that with the emergence of a large amount of foreign language content in the domestic Internet environment, the pressure on Xiaohongshu's review side is enormous…difference in expression habits will undoubtedly easily lead to blind spots in review, not to mention that there are differences in the standards of speech expression at home and abroad. Once low-quality content or even dangerous remarks appear, it may become the straw that breaks the camel's back for a content platform.

But as Western excitement over Xiaohongshu quickly cooled, concerns dissipated. It’s unclear how many Americans came and went, but the retention rate was low enough that efforts to fully translate the app have been all but abandoned. Though comments and titles have become decipherable in the months since I set my language preferences to ‘English’, error messages are still presented in Chinese characters. Similarly, it seems English-language moderation efforts have come to a near standstill.

This has, consequently, led me to a particularly strange, dark corner of the platform. One far less welcoming, far from the “lifestyle bible” it is intended to be.

Perhaps I lingered longer than I should have on the Inner Mongolian rancher, dressed in blue jeans, huddled around an orange glowing fire alongside a horse and two traditional throat singers. A plethora of comments from Texans and a warm thank you message specifically addressed to “North American netizens” confirmed that a large number of other Westerners landed on this profile, too. The video itself was hardly nefarious, but glamorized a picturesque libertarian-adjacent countryside lifestyle in much the same way an episode of Yellowstone might. Maybe this signaled a desire for something grittier, less tame than all the pretty cosmopolitan women had to offer.

Maybe it was during the Chinese New Year, when I unintentionally stumbled upon a short clip of a pig being slaughtered, throat slit ear to ear, presumably for holiday celebrations to come. That same day, the app suggested a video of a human corpse slumped on the side of a dirt road in Myanmar12.

In all likelihood, it wasn’t a single video that triggered the shift at all. It was a culmination of everything I viewed that probably signaled to the Xiaohongshu algorithm that my eyes are those of an outlier. In place of the innocent memes I half understood and earnest cultural exchange, my feed has gradually started to prioritize fresher, uglier content, much of which is heavily politicized.

A significant portion of the limited posts I can decipher come from American IP addresses, expressing frustration with a Western online ecosystem ruled by the tech oligarchs. So long as criticisms of Xi and Tiananmen and Taiwan are avoided, just about any subject, conveyed in every crass word conceivable, seems to be fair game13. Extreme viewpoints across the spectrum coexist in relative harmony. A raw milk enthusiast will denounce the practice of gender affirming surgery as an affront to nature, closely flanked by a self-proclaimed communist revolutionary glorifying the widespread Soviet Union political purges of the 1930s. Red-pilled men (evidently oblivious of Xiaohongshu’s demographics) will pitch online courses on finding “traditional” Southeast Asian wives far more desirable than the shrill, self-righteous hags in America.

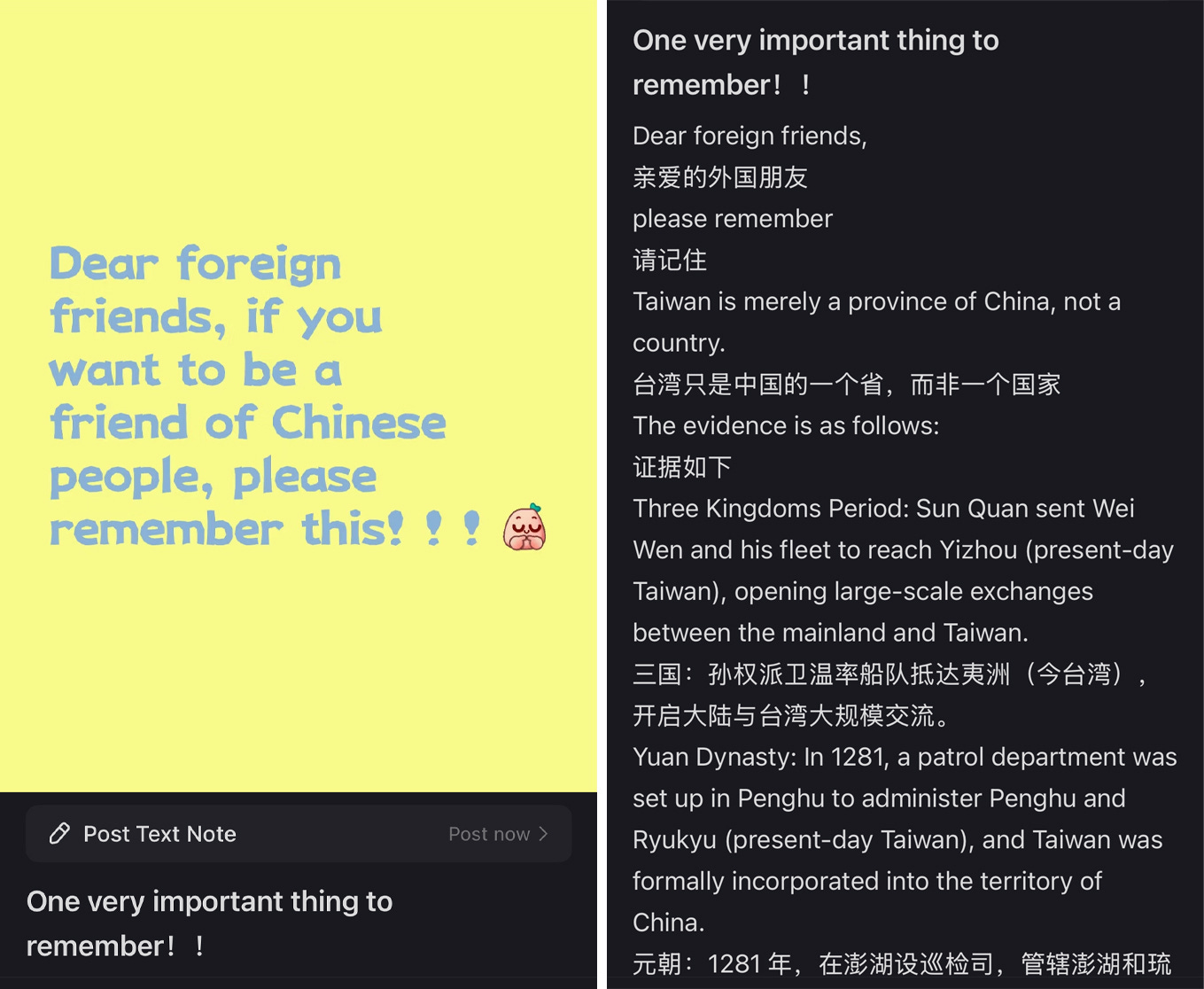

Some English-language posts come from Chinese netizens speaking directly to the small population of leftover TikTok refugees. Plenty are simply requests for a foreign friend to practice English with. Others exclusively exist to brag about China’s overall superiority, criticize Western societal flaws, and aggressively address outsider “misconceptions” that contradict CCP narrative.

But, curiously, a great deal of what I encounter has little to do with China or the United States at all. Instead, jumbled among the cute clips of hippopotamuses snacking on orange pumpkins, is a hateful geopolitical circus.

It started with the stray, reasonably worded post expressing support for Gaza. This in itself was not particularly surprising – many TikTok refugees cited the alleged censorship of pro-Palestinian content as a motivating factor in making the switch to Xiaohongshu. However, as months have passed, the posts have intensified, both in volume and messaging. Calls for peace and ceasefire at some point morphed into antisemitic canards of Jews from “Israhell” controlling mainstream media. In response, accounts that exclusively feature pro-Israel content have started to emerge in recent months, showcasing AI-generated lions wrapped in Stars of David, blue glittery hearts punctuated with strong-arm emojis and over-the-top praise for the State of Israel. The last several weeks have brought with them an onslaught of posts about Iran. For every post cheering on the potential downfall of the Ayatollah, there exists praise for bombs bursting in the streets of Tel Aviv.

This cat-and-mouse dynamic of post exchange is hardly confined to conflict in the Middle East, though. My feed is also inundated with Indians and Pakistanis trading blows, Ukrainians and Russians vying against one another.

The most fascinating aspect of these posts is that many appear to be designed to succeed on Xiaohongshu, specifically. They are, for lack of a better word, cute. Hateful, xenophobic words are frequently rendered in whimsical fonts, flanked by colorful cartoon cats and dogs. Fashionable women in traditional outfits bear machine guns. Guillotines and Molotov cocktails bear mischievous grins while the United States is anthropomorphized as an anime girl.

From what I’ve been told by several Chinese Xiaohongshu users, the degree of vitriol on my feed is outside the norm. Perhaps my results stem from the comparatively small pool of English-language content available to me. Morbid curiosity may have driven me to this point, unintentionally informing some sophisticated algorithm. Either way, the line between calculated bot and nationalist-fueled lunacy has blurred, and sometimes I fear I’ll never find my way back to that place that briefly inspired optimism. They are locked behind the BabySolidFood tags of the world, trapped somewhere beyond my comprehension, written in codes and languages that even the most advanced technology cannot decipher perfectly.

This brings me back to that vlog from North Korea.

It remains unclear to me whether the vlog is the work of a student catering to the booming Chinese sheconomy that thrives on Xiaohongshu, or if it is a masterfully executed piece of cutecore propaganda made especially for a young generation of aesthetic-obsessed netizens with very short attention spans. Either way, it is just performative enough to spark envy and convince viewers, if only for a moment, that North Korea could be a desirable vacation destination rather than an autocratic hellscape. Simultaneously, through imperfect cuts and handheld shots, it conveys a sense of something real that young audiences and consumers yearn for.

It’s hard to resist feeling cynical among the slew of concentrated hate posts, the suggestions among comments that what I’m seeing is an illusion of some sort. There is no way of ruling out that that “something real” about the vlog is, in actuality, entirely premeditated and deceitful.

However, in my pursuit of an answer to a question I can’t quite articulate, I stumbled across a February 2025 article detailing the popularity of Shenyang Taoxian International Airport’s KFC location among Pyongyang travellers. Because the flight between Shenyang and Pyongyang is only about an hour, travellers re-entering North Korea will bring with them still-warm chicken and hamburgers14 for loved ones waiting at the airport. In the capital, it’s said that rumors of KFC’s tasty offerings have spread for years, to the point where airport personnel have given up on confiscating sandwiches despite the implicitly American branding.

This article does not solve the mystery entirely. I’ve still got no idea how the ketchup ended up in a restaurant setting, or where the McDonald’s packet came from. Even so, it suggests a high likelihood that there isn’t some amazing story behind their presence at all.

Nonetheless, the ketchup packets continue to turn the gears in my head. Because they are amazing, hinting at some base human connection, some mutual craving and shared experience with people that couldn’t feel further away. It’s small, I know, but these gems of understanding continue to invite my wandering eyes back to Xiaohongshu. Scouring the corners of the app – English, Chinese, and the spaces in between – there’s more to be found beyond fervent manufactured hatred, glaring as it may be.

I’ve witnessed women call one another sisters, and lovers share their innermost feelings. I’ve visited places that I may not have the fortune of experiencing in my limited lifetime, and I’ve laughed at jokes transmitted from thousands of miles away written in intricate characters I’ll likely never be able to interpret on my own.

And, despite obvious cultural barriers, there’s evidence that the feeling remains mutual.

Just a few days ago, I came across a video made by a still-active American Xiaohongshu user named Big Ren. He’s a foul-mouthed, leather-clad man with a burly beard, a big belly, and a knife always on hand. Every Saturday, he stands in his driveway, stabs a hole in a 40 oz can of Budweiser, and drinks the contents as fast as he possibly can.

Purely by coincidence, the next spoon-fed post was a simple question written in English: “Do you regret letting the Americans in this app?”

With Big Ren – the antithesis of a typical Xiaohongshu user – fresh in my mind, I feared for the worst waiting for me in the comment section.

But, to my surprise, the overwhelming majority of responses expressed gratitude for the opportunity to connect. One particularly poetic translated answer from a Fujian IP address has stayed with me:

“A group of different skin colors and ethnicities hold hands, running freely on the green field. They don’t need to fully understand each other’s language, yet they can penetrate all barriers with their eyes, gestures, and laughter, sharing the pure joy under the same sun – this pure, natural scene of “being together”, doesn’t it herald the most authentic and moving vision of the future world?

The project of dismatling mental barriers is vast, but it begins with the awakening within each of us. The world is not a destined labyrinth of division; it is a magnificent tapestry waiting to be woven together. Every thread that breaks barriers, attempts understanding, and releases goodwill holds the potential to change the overall picture. When we choose to dismantle rather than build walls, to connect rather than isolate, that planet once fragmented by countless barriers will ultimately, under the gentle repair of countless hands, reveal its complete and brilliant face as “one world”.

In that moment, I thought of Pangzai, an unlikely internet celebrity who made the rounds several years ago. Famous for adopting a “tornado” method to quickly consume green bottles of beer, he posted videos of himself cooking, smoking cigarettes, and breaking bricks on a Douyin competitor called Kuaishou. In 2018, his account was suspended due to its promotion of “unhealthy” behaviour. However, his videos were subsequently cross-posted onto Twitter the following year, where he gained a cult following among Western audiences. Despite his inability to speak English and the outlandish nature of some of the stunts, people (myself included) gravitated to Pangzai’s enthusiasm to share everyday life as an ordinary man living in Northern China’s sleepy countryside.

Big Ren is not so different, deep down. We are more alike than not. Despite the oceans and firewalls separating us, we are sisters.

And as Big Ren guzzles beers over and over again indefinitely, the loudest voices momentarily subside. What’s left is simple gratitude. A thankfulness to discover all it is that we share – one microscopic detail at a time.

If you enjoyed this essay and want to say thanks, please consider buying me a coffee 😎

Pronounced "shau-hong-shoo"

This promotional video of Munsu Water Park in Pyongyang illustrates what I mean.

According to multiple sources, the “red” in RedNote is a callback to co-founder Mao Wenchao’s alma mater (Stanford Business School) and former employer (Bain & Company), and the translated name is purely coincidental. The “Little Red Book” nickname in reference to Quotations from Chairman Mao (毛主席语录) is largely used outside of China, and the phrase “xiaohongshu” does not hold the same political connotations in Chinese. Instead, the compilation of Mao quotations is informally known as"hongbaoshu" (红宝书), or "red treasured book".

Shopping is a big deal for many Chinese tourists, sometimes serving as a prime motivator for travel. One 2017 study conducted by Nielsen found that 47% of Chinese tourists traveling abroad listed shopping as a “top priority”. The same study found that outbound Chinese tourists spent an average of 25% of their on-location travel expenses on shopping. In comparison, only 19% of budgets went toward accommodations, 16% toward dining, and 14% toward visiting local attractions.

In 2021, just one in ten Xiaohongshu users were male. An article published in 2022 reported that an advertising campaign toting Xiaohongshu as a place to meet ‘beautiful ladies’ launched on Hupu Sports, a site extremely popular among Chinese men. Xiaohongshu has also recruited influencers from traditionally male niches to try to even the gender imbalance.

Think gyms staffed with female trainers that only offer memberships to female clientele, hostels whose rooms are solely reserved for female travelers, etc.

Throughout the 20th century, certain elements of feminism have been embraced. Revolutionary Operas penned during the Cultural Revolution largely centered around female protagonists oppressed by misogyny. “Iron Girl” propaganda, not unlike America’s Rosie the Riveter, showcased working women capable of taking on labor-intensive jobs traditionally reserved for men. However, modern feminists who choose to speak up about persisting societal inequalities are frequently denounced as incendiary upstarts. In 2015, a group of women dubbed the “Feminist Five” were imprisoned for planning (but not carrying out) a demonstration against widespread sexual harassment on public transit. In 2018, #MeToo allegations were heavily censored and denounced by nationalist bloggers under the impression that the movement was manufactured by "Western forces to tear Chinese society apart”. Popular feminist outlets have been permanently banned on WeChat and Weibo, and in 2022 the Communist Youth League of China described extreme feminism as "a poisonous tumour on the Internet."

For years, President Xi Jinping has urged Chinese women to return to domestic spheres and focus on family as a means of combatting the 4-2-1 phenomenon.

This is not to suggest that Western advertisers are especially more progressive in addressing menstruation – the same blue-in-place-of-red visual is common in the United States as well.

To be clear, PAFACA would not ban TikTok outright. Rather, it would impose insurmountable fines ($5000 USD per user) on companies like Google, Apple, and Oracle, that might distribute and host the TikTok app.

Chinese-English translation is notoriously challenging, and literal word-for-word automated translations can be difficult to comprehend. The translation AI implemented on Xiaohongshu, while imperfect, goes a step further than most rudimentary translators by considering the greater context of comments as well as deciphering the wordplay, idioms, and internet slang essential to grasping the intended meaning of a given statement.

Incidentally, my conversation with Tianyu Fang shed some light on how a pig slaughter quickly transitioned to a corpse in Myanmar. In January, Chinese actor Wang Xing was abducted by a Myanmarese fraud factory and forced against his will participate in a “pig butchering scam”, in which a scammer builds trust with a victim and extorts large quantites of money. His subsequent rescue by Thai police was widely reported among Chinese media outlets.

Yes, KFC locations in China offer hamburgers!