Uncovering the Hidden History of Shrek

Thanks to the efforts of a few lost media enthusiasts, dozens of forgotten – and decidedly odd – snippets from the earliest iterations of an innovative animation have recently surfaced.

This month, a small but long sought-after snippet of animation history unexpectedly surfaced from a quiet corner of the internet. For years, it was considered a white whale among a certain subset of internet sleuths. And at the center of it all? Everyone’s favorite green and grouchy ogre, Shrek.

To the uninitiated, it’s hard to believe that a franchise worth billions of dollars could possibly have any stone1 left unturned. Alongside four feature films and roughly a dozen shorts and specials, Shrek has spawned everything from video games to theme park attractions. As one of the most influential and beloved personas of the early 00s, the children that grew up with the animated hit have spent the last decade2 churning out Shrek memes across the internet. Whether the fandom is satirical or sincere (or somewhere in between), our collective Shrek-session is so intense that other creatives have banded together over the years to produce Shrek-inspired works of their own. Professional actors and musicians have come together to perform Shrek The Musical on Broadway and West End, and in 2018 over 200 amateur artists recreated the original film scene-by-scene for the Youtube collaboration Shrek Retold.

What more could there be that any self-respecting Shrek fan hasn’t already consumed ad nauseam?

As it turns out, quite a bit. And the 7-second scene unearthed this month only represents the tip of a secret Shrek iceberg.

Before diving into the finer details, a little bit of context concerning Shrek’s origins is necessary. Though the Shrek films we all know and love today didn’t debut until 2001, Shrek’s genesis came over a decade earlier.

Well into his 80s, children’s book author William Steig penned a story simply titled Shrek! in 1990. Much like the eponymous movie ogre, this version of Shrek is a societal outsider completely content with being a vile, repugnant creature. Though the book includes some classic fairy tale tropes (a princess bride-to-be, a witch with a cauldron of bats), it’s primarily a story of finding confidence and self-esteem regardless of who (or what) you may be. Shortly after the book’s publication, it became a bedtime favorite of producer John H. Williams’ sons. Inspired by the “irreverent, iconoclastic” nature of the main character, Williams pitched the concept of a Shrek-inspired feature to fellow film producer Jeffrey Katzenberg.

At the time, Katzenberg had been recently ousted from his position at the head of Disney’s motion picture division due to ongoing conflicts with CEO Michael Eisner. However, thanks to his prominence during the Disney Renaissance and key role in Disney’s acquisition of Pixar, he had no trouble finding a new job to occupy his time. Alongside director Steven Spielberg and business magnate David Geffen, Katzenberg founded DreamWorks in 1994. As it turned out, Spielberg had coincidentally purchased the rights to Steig’s book back in 1991, at the time hoping to one day turn it into a traditionally animated feature. The stars seemed to align, and Shrek spearheaded the fledgling DreamWorks animation studio.

This may come as a surprise to some, as Shrek did not actually debut in theaters until 2001. Antz (1998), The Road to El Dorado (1998), and Chicken Run (2000) were completed and released before Shrek – despite the fact that all three started active development after production for Shrek had commenced 3. So what happened in those 6 or 7 years between Shrek's start and finish?

The truth is that by the end of 1997, an early iteration of Shrek was creeping close to completion. But it hardly resembled the animation that would ultimately grace screens worldwide three and a half years later.

Originally, comedian Chris Farley was set to star as the irritable ogre. Pigeonholed for years into roles calling for boisterous, bumbling buffoons because of his size, Farley was anxious to expand his repertoire and show audiences that he could be more than comic relief. Taking on the role of Shrek was a no-brainer, as the movie adaptation of the ogre seemed as though it was specifically created with the actor in mind. Unlike the original storybook Shrek, Farley’s version featured a teenage ogre that dreamed of forging friendships and seemed somewhat insecure with life as a hideous, frightening monster. Just like the actor portraying him, the good-natured, deeply sensitive character longed to be seen and appreciated beyond his superficial appearances.

But it wasn’t just the main character that was unrecognizable. The artistic style of the film was drastically different as well. Unlike the relatively straightforward computer animation used in the final film, Shrek was originally going to be captured using an unusual hybrid of live-action film and CG animation. Essentially, miniature sets of locales within the Shrek universe were created, and then animations of the main characters were to be spliced into scenes as needed. To make the movements as human as possible (and, no doubt, make the most of Farley’s aptitude for physical comedy), the team used motion capture technology to record the actor’s gestures and apply them to computer-animated models.

Though this would have made Shrek stylistically very unique, when a test for the hybrid animation was finally ready to be screened, Katzenberg reportedly deemed that it looked terrible and “it didn’t work”. Forced backward, DreamWorks eventually turned to help creating a fully CG animated film from the animators at Pacific Data Images, who had already been enlisted to produce Antz. Because these animators were still putting the finishing touches on the aforementioned insect-centric feature, art production wasn’t able to resume working on Shrek in any real capacity until 1998.

In the time between the failed screening and the PDI team’s attempt to revamp Shrek’s design, Chris Farley’s health was in serious visible decline. In December 1997, the comedic legend overdosed in his Chicago apartment and was declared dead at just 33 years old. Though the number varies between sources, Farley had completed somewhere between 80-95% of Shrek’s lines at the time of his passing.

Tragedy aside, this left the Shrek production team at a difficult crossroads. Shrek was Farley, and without their star, it was unclear how to proceed with the film. Initially, there was talk of hiring a Farley impersonator to complete the last few bits of the script. Ultimately, this was decided against. Eventually, Mike Myers was re-cast to fill the starring role, but only under the condition that the script be entirely reworked. And so, almost all traces of the original film disappeared in favor of Myers’ sardonic portrayal and faux Scottish brogue. The Shrek that almost was became lost media, buried far beneath the polished veneer of the Shrek that would go on to become one of the single most influential animations of all time.

Whenever I start to speak about lost media, I’m almost always asked to clarify what, exactly, lost media is. Put simply, it’s exactly what it sounds like; works that have been lost to time for one reason or another.

Though the term itself isn’t especially commonplace, it’s far from being a novel concept. Works from philosophers like Heraclitus and Pythagoras are considered lost media because all that we know of their philosophy comes from surviving texts that make references to them. Author Terry Prachett’s unfinished manuscripts became lost media when, in accordance with his will, his computer’s hard drive was crushed by a steam roller. Artworks plundered by Nazi Germany and silent nitrate film archives destroyed by spontaneous combustion are considered lost media, too.

But not all lost media disappears as glamorously as that. Lost media isn’t always “lost” because it’s been swept away by some natural disaster, stolen by a nefarious force, or purposely hidden from prying eyes. Rather, media is often lost when people deem that a piece of media isn’t worth preserving or sharing. Inevitably, a day comes when no one seems to be able to dig up any trace that this “lesser” media ever existed at all. For instance, many early television broadcasts have been lost simply because the earliest TV pioneers couldn’t grasp the appeal of airing a rerun and consequently taped over their broadcasts.

Lost media doesn’t necessarily have to be completed media, either. Outtakes, drafts, and tests are often scrapped or forgotten because of their inherent imperfections. This is why the rough-edged Farley Shrek is often considered lost media. While there’s a high likelihood that completed pieces of the project exist somewhere in the depths of a DreamWorks-owned storage facility or in a bygone CG animation portfolio, there’s also a very high likelihood that this content will never purposely reach a wider public audience.

That said, lost media doesn’t necessarily always remain lost. People constantly find films once considered lost popping up on unmarked VHS tapes at suburban yard sales, or long-missing publications collecting dust in attic boxes. And, increasingly so in the last two decades, lost media sometimes spontaneously appears out of some forgotten crevice of the world wide web.

For this reason, contemporary lost media enthusiasts sometimes view themselves as sort of digital archeologists. A sort of moral responsibility drives these individuals to save and recover as much creative content as possible by whatever means necessary. Redditor freecouch0987 encapsulates this philosophy in the following comment, written in response to a thread regarding HBO’s recent animation purge:

“All of this happening only solidifies my opinion that we have an obligation to preserve and share media whenever we can regardless of the legality of doing so. Companies are willingly allowing works of literature and art to be thrown out with no respect to creators or future generations”

Others simply enjoy the thrill of the hunt. From the comfort of home, it is possible to dig up clues from long abandoned sources and sift through hours of leads without breaking a sweat. After all, what greater trove of treasures could there be than an ever-expanding universe of information accessible in mere seconds? With the barriers of higher education and funding removed, the only thing necessary to make a great discovery is limitless patience and a little bit of luck.

Farley’s Shrek has long been considered one of the lost media community’s holy grails. In part, this likely has to do with Shrek’s online transcendence from a nostalgic childhood friend to the mythical subject of endless metameme. But underneath the irony-laced chuckles lies something truly fascinating about this film that never was. It is a preservation of a beloved comedian’s final days on Earth, filled with the trace inspirations that would eventually go on to fuel one of the world’s most popular franchises. It is imbued with a rawness and sincerity not present in the sea of polished, mass-marketed materials that have been readily available to Millennials and Gen Z for their entire lives. We know that its existence is more than just a murmur or rumor generated by some pimpled teenager on a message board, but it still manages to retain the mythical qualities of something unreachable, unattainable.

And that makes it irresistible.

Just as Captain Ahab obsessively scoured oceans in search of Moby Dick, so too has the lost media community pursued this curious footnote in the development of Shrek.

The quest for Farley’s lost Shrek initially took off back in 2017. Though it wasn’t exactly a secret that Farley had worked on the film before Mike Myers came into the picture, as far as the general public was concerned information on what Farley’s rendition of the story might have looked like was a complete mystery. That is, until a Youtuber known by the handle unclesporkums happened upon an expired eBay listing for a Farley-era storyboard 4.

The storyboard depicted Shrek encountering a horrified mugger in a moonlit alley. After the mugger insults Shrek’s mother, the ogre sends his puny adversary flying into the night sky. The boards also specified that this segment would include Shrek singing and dancing to James Brown’s 1965 single "I Got You (I Feel Good)”. Unclesporkums proceeded to compile the pixelated frames and proposed dialogue into a single video and affectionately dubbed the hypothetical animation “I Feel Good”.

Evidence that shreds of Farley’s Shrek still existed piqued the interest of a few determined lost media enthusiasts. That excitement magnified when another 2016 eBay listing for early animation tests recorded on an unmarked VHS surfaced and all but confirmed the production of “I Feel Good” with the following description:

For this test, Shrek's design was based on Mike Ploog's drawings. The story is simple: Shrek enters a gated city at night belting out the song 'I Feel Good' and is accosted by a 'Mugger' suspended from a rope. Shrek plays with him then grabs him by the neck, stretches him on his rope and springs him into the sky against the moon…It is also silent. After Chris Farley (the original voice) passed, all audio of his voice was removed. The easiest way to do that was to remove the whole track. You can still 'lip-read' him at the end saying "Bite Me!"

The only problem? By the time this listing was unearthed by lost media enthusiasts, it had already been sold – likely to a private collector unwilling to leak the animation online. The promising lead culminated in a dead end.

But knowledge that “I Feel Good” indeed existed somewhere – possibly in more than one place – ignited a fire among the most inquisitive seekers. On platforms including Discord and Reddit, members of the insular lost media community would share tips and collaborate with one another. But for five years, nothing of note emerged on the Shrek front5 outside of a couple of closeup stills of the ogre's expression.

That is, until this summer, when Lost Media Wiki user DingleManBoy discovered 31 previously unseen “I Feel Good” frames on the Vimeo demo reel of an animator associated with Shrek’s pre-production. The dry spell was over, and the new crumbs of information rekindled widespread interest in the obscure proto-Shrek.

Midway through August, in the dead of night, two Redditors (using the handles Hotter_Cooler and AccomplishedWorld823) made a breakthrough after five years of rooting around. After an exhaustive search through every individual name credited under the movie’s Los Angeles pre-production phase, another animation reel was found on Vimeo. And against all odds, there it was – seven uninterrupted seconds of the “I Feel Good” footage in all its original glory.

Further research eventually lead to another segment from the “I Feel Good” sequence, this time featuring the mugger6.

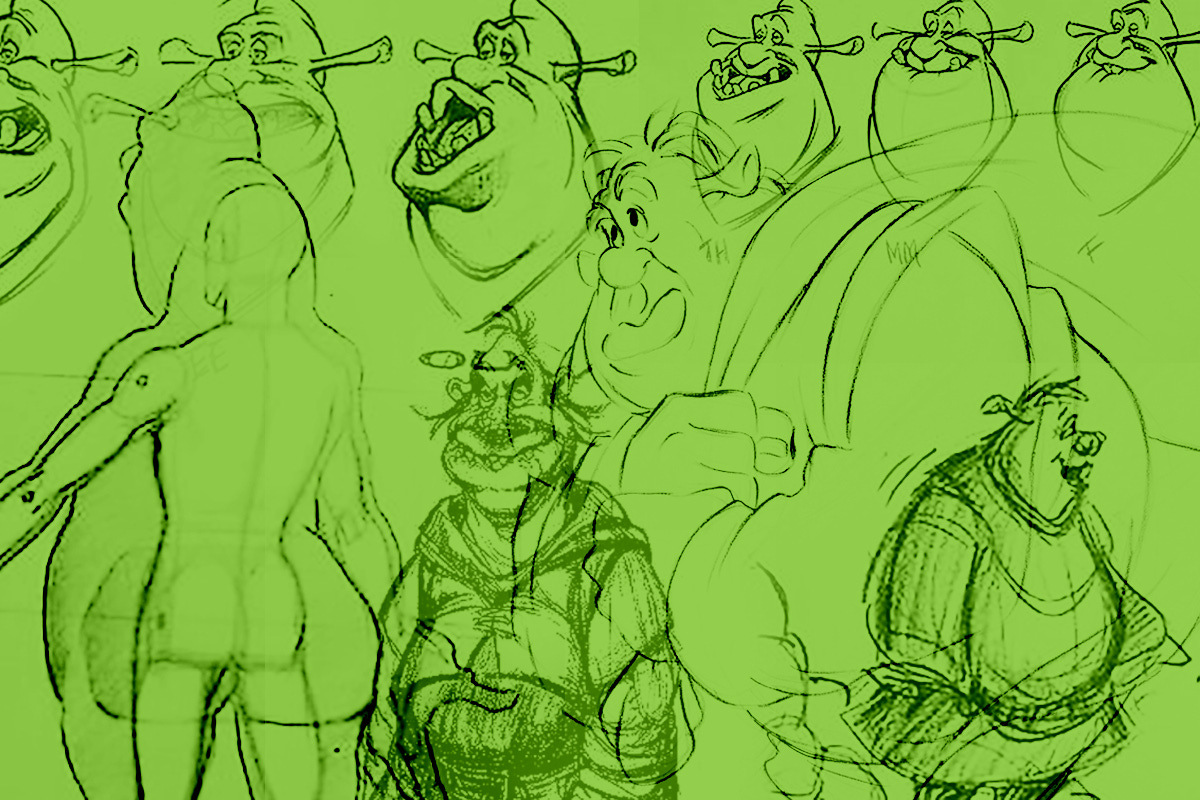

As one might expect, the monster in these snippets is Shrek-like, but not quite Shrek. His crooked smile is grotesquely exaggerated, his proportions far less human than what we’d see in the final product. As he sways through the moonlight, it’s clear that this creature crosses into the uncanny valley in a way his descendant does not. It is not difficult to conceive of an ex-Disney exec writing this off as “unmarketable”.

But, as imperfect as this iteration is, there is a certain charm to the goofy caricature. Like the onions Shrek so dearly loves7, when we peel back the unpalatable exterior, there’s something beautiful to be found. Even in this vignette, it’s clear that the subversion of classic fairy tale tropes is still an integral part of this clumsy green James Brown impersonator’s soul. And now, after 26 years, we can confidently confirm that many of the qualities that make Shrek so well loved were present in even the earliest iterations of the ogre.

On the path to finding “I Feel Good”, enthusiasts have also uncovered fragments of other early Shrek-related content that almost certainly would have been lost otherwise.

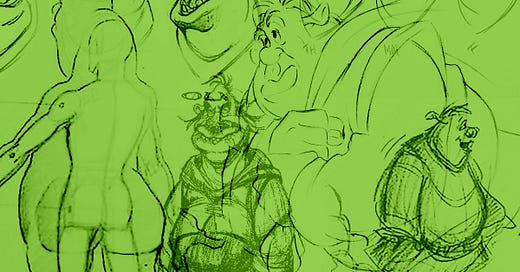

Over the last two weeks, hundreds of preliminary Shrek sketches have been uncovered, ranging from simple doodles of stubby fingers to an amorous Dragon leading Donkey to a heart-shaped marital bed. Discord users found a silent Quicktime video featuring a completed storyboard of Shrek entering a tavern, getting into a violent confrontation with an unruly patron, and ultimately walking away after catching his own contorted reflection in a nearby mirror.

But my personal favorite – and perhaps one of the most remarkable – of the recent finds is a test animation that’s actually paired with Farley’s voice. It’s not much, and it’s not the first of Farley’s voice acting that’s surfaced. The animation is so rough, in fact, that Shrek’s clothes have yet to be added and the green humanoid mass is set against an entirely black background.

Despite the detail it lacks, though, there’s something heartbreakingly genuine about the words that leave this incomplete draft’s mouth. As a few commenters have already stated on this particular Youtube video, the simple shift in tone that occurs when Shrek realizes that he’s not inherently repulsive is poignant – indicative of an unrealized character that died alongside his far too young real-world counterpart and never got to be. Without a doubt, it’s tragic.

But beneath the layer of tragedy is something greater, something less shrouded in darkness. As unlikely as it seems, after nearly three decades of neglect, there’s been an outpour of appreciation for the Shrek that never was, now that it has found its way to our eyes. Through comments, likes, and shares, we see a celebration of artistic efforts, entirely independent of commercial value.

I like to think that Farley and the forgotten artists alike would gain a certain satisfaction in knowing the steadfast dedication internet strangers have poured into resurrecting this long-forgotten prototype from disparate scraps. It is, above all, proof of the audience’s overwhelming acceptance for a Shrek without the shields of snark and sarcasm – imperfections and all.

This is a very rough, extremely conservative estimate. I’m not really sure how one would go about pinpointing the first Shrek meme, but it’s generally agreed upon that the 2013 4chan green text stories known as “Shrek is Love, Shrek is Life” triggered many of crude, absurdist Shrek memes that are now commonplace.

The Prince of Egypt (1998) was also released before Shrek, but it seems that development on Egypt started before Shrek as Katzenberg had already pitched the idea to Disney prior to his departure.

It can be inferred that this storyboard came from late special effects artist Tim Lawrence, which significantly reduces the likelihood that “I Feel Good” is a fan-made fraud. While the archived eBay listing doesn’t have the seller’s user information, we do know that seller also sold a maquette of the mugger featured in the “I Feel Good” storyboard around the same time. For the maquette listing, the seller mentions that at the time of the mugger’s creation “we’d moved out of my garage” in favor of sculptor Tom Hester’s North Hollywood studio. In a later 2016 listing actually signed by Tim Lawrence (also featuring early Shrek animation tests), Lawrence states that “Shrek began in my home studio (garage) on the corner of Colfax and Chandler in N. Hollywood”. Linking the early phases of the movie to Los Angeles also proved to be a crucial clue in tracking down further remains of Farley’s Shrek.

To be clear, the lost media community expands far beyond Shrek and has worked together to find plenty of previously lost media. Since the Lost Media Wiki’s conception in 2012 and the subreddit’s creation in 2015, some notable finds from the greater lost media community include a 1997 demo of Pokemon Gold and Silver (complete with monsters left on the cutting room floor) and a controversial episode of Sesame Street, guest starring Margaret Hamilton reprising her Wizard of Oz (1939) role as the Wicked Witch of the West.

Fun fact: according to production notes, the mugger cut from the final film was slated to be voiced by Tom Kenny, the actor most famous for voicing Spongebob Squarepants.

Interestingly, we currently know of only two scenes stemming from Farley’s Shrek that were reworked into Myers’ final product (as oppose to being scrapped entirely). One of them is the scene in which Shrek relays to Donkey that “ogres are like onions”

Fantastic read, thank you Meghan!

So cool! I had no idea they’d gotten so far on the Farley version of Shrek. I’ll be following this lost media hunt from now on!