What the Hell is Up with Dilbert

The normally innocuous workplace comic strip is arguably trying to get itself canceled after three decades in syndication. But why?

Lately, cartoonist Scott Adams has made a habit of getting himself into trouble.

This may come as a surprise to those only familiar with the artist-turned-author through Dilbert, the mild-mannered but perpetually-frustrated office worker who has graced newspaper comics worldwide. For the past three decades, the bespectacled engineer has appeared alongside the likes of Snoopy and Garfield across 2,000 or so publications, reaching approximately 150 million readers. Considering the prolonged death spiral of the newspaper industry as a whole, you might suspect that now would be as good a time as any for Adams to fade into obscurity to enjoy a quiet retirement funded by his Dilbert-generated fortune. Instead, he’s been landing himself as the internet’s villain du jour at a shocking rate.

Following July 4th’s Highland Park shooting, Adams sparked online ire after sharing a series of tweets concerning America’s “dangerous young man problem”. In said thread, he suggested that parents seeking help for their troubled teenage boys have just two options: to kill their own sons or “watch people die”. “If you think there is a third choice…you are living in a delusion,” he states before proposing that a hypothetical solution might lie in sequestering broken boys to a penal colony of sorts entirely removed from the rest of society. For a number of obvious reasons, many deemed the thread both ridiculous and callous.

However, a quick look into Scott Adams’s social media reveals that his “dangerous young man” tweets weren’t exactly out of character. If one thing could be said of the man, it’s that he’s not afraid to voice controversial opinions that counter mainstream viewpoints. For instance, just a few days ago he used his Twitter platform to insinuate that infamous sex offender Jeffrey Epstein might still be alive.

What is strange is that Scott Adams’s contentious opinions are no longer strictly relegated to social media. Recently, they’ve started spilling over into the fictional Dilbert-verse.

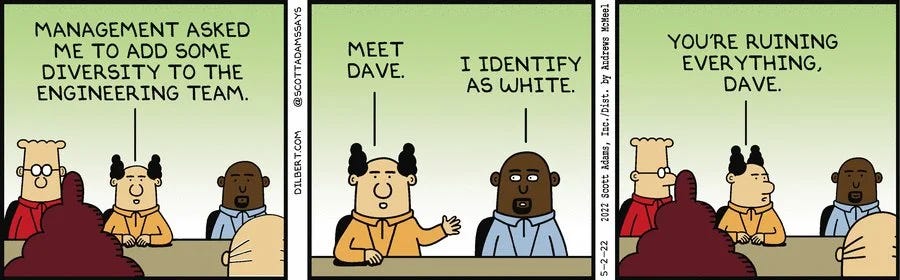

In a series of strips published in May 2022, the series introduced a new employee, Dave, to Dilbert’s workplace. Despite being in syndication for the last 33 years, Dave’s inclusion marks the first time the comic has featured a Black character. Unfortunately, the three-panel, 21-word introduction acknowledges that Dave is hired merely as an act of workplace tokenism before wrapping up with what appears to be an attempt at a thinly-veiled transphobic joke.

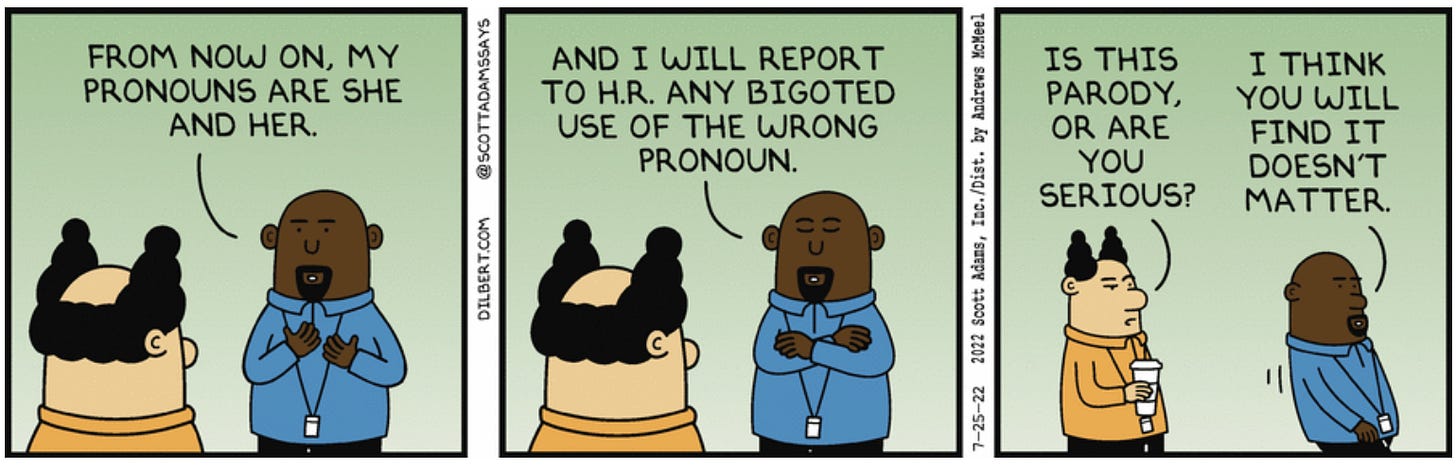

After disappearing for two months, Dave reemerged on July 25th with an even more on-the-nose jab at the transgender/non-binary community. This time, Dave threatens to report PHB (Pointy-Haired Boss) to the company’s HR department should he misgender the new engineer. It is then implied that Dave has switched preferred pronouns with the intent of catching cohorts in a trap rather than out of any true reflection of self. Much to Adams's frustration, publishers evidently switched Dave’s skin color to white, presumably in some attempt to make the cartoon less offensive1.

But recent Dilbert controversy doesn’t begin or end with Dave. In late June, Adams took to social media to complain that one of his strips was pulled from many papers for being too controversial. The offending comic features Wally (Dilbert’s chronically lazy coworker) weasel his was out of work by identifying as a “birthing human” and complaining of cramps. This, of course, mirrors ongoing backlash in certain conservative circles over the use of gender-neutral terms in place of the word ‘woman’ in order to include trans men and non-binary individuals in increasingly pertinent conversations about bodily autonomy.

So aggravated with being stifled by the “woke” masses is Adams that he recently shared a poll on Twitter to ask followers whether or not he should force himself into retirement by “getting cancelled”. In some ways, these online outbursts make sense. Many would argue that Western politics are more polarized now than ever before, and the accessibility and addictive nature of social media makes it incredibly easy to publicize one’s every thought. What’s difficult to understand, though, is why Adams is toying with the idea of nuking his multi-million dollar Dilbert brand. Should he choose, Adams could sit back and comfortably collect royalties from desk calendars for the rest of his life. For what reason would a person risk that sort of stability?

In order to understand why personal politics are bleeding into the normally tranquil realm of the funny pages, the first step one must take is to try to understand the core nature of Dilbert.

Sometime in the late 1980s, an office worker named Scott Adams bought himself a book on how to become a cartoonist. It had always been a dream of the Pacific Bell Telephone Company employee, who still doodled in the margins of his papers well into adulthood. In order to retain a steady income, he would toil away in a cubicle during the day and stay up late into the night in order to practice drawing panels. On a whim, he eventually sent a few samples to a handful of editorial syndicates. By 1989, his drawings graced the pages of newspapers around the country.

This was how Dilbert entered the world. But it was only over time that he developed into a tortured hero of sorts for white-collar workers. When he initially debuted, Dilbert was actually a rather creative (if socially inept) scientist, often in the middle of conducting an experiment or constructing an invention. But one major factor ultimately steered the cartoon in an entirely different direction – Scott Adams’s decision to begin including his email address alongside his panels.

Though the use of email was not nearly as widespread then as it is today, early readers began flooding the fledgling cartoonist with feedback. And, as it turns out, many of those early readers took to the storylines revolving around Dilbert’s work life. As a result, the setting of Dilbert increasingly shifted from the outside world to the office. By 1993, Dilbert was rarely featured doing anything unrelated to his job.

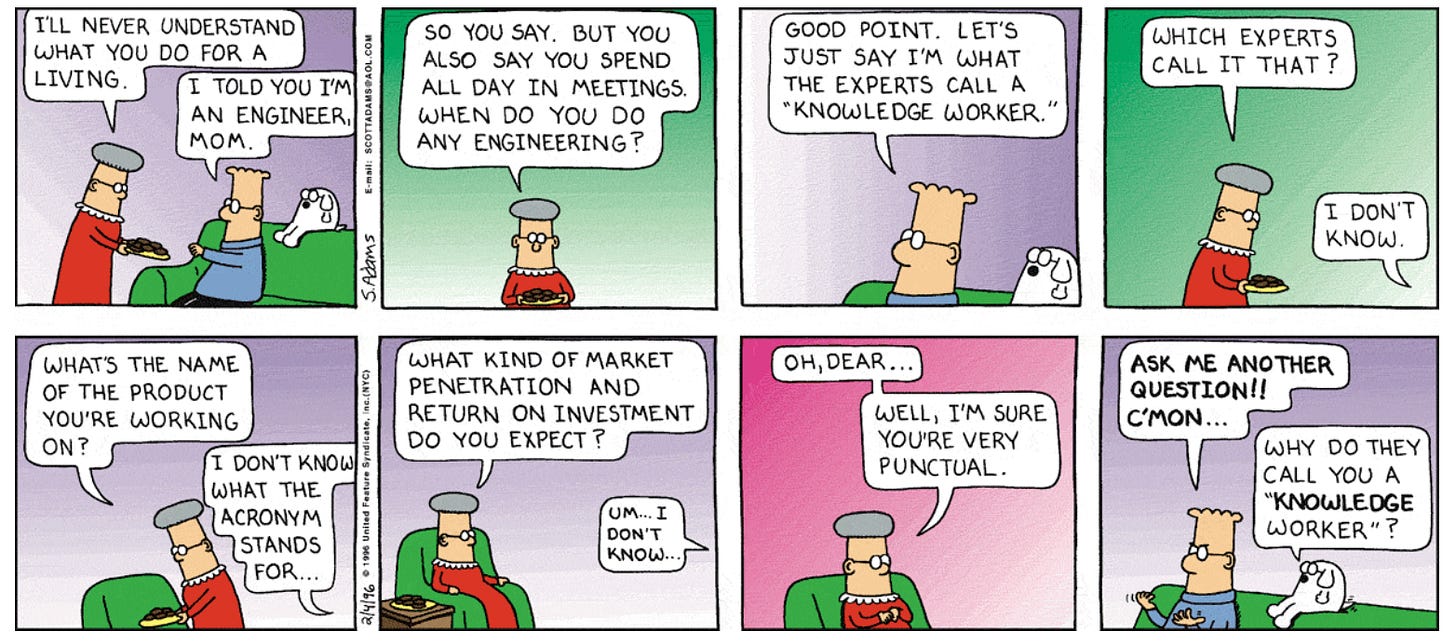

Unfortunately, Dilbert is cursed with enough cognizance to recognize all of the ineptitude and injustices that happen in his workplace. However, he’s either unable or unwilling to actually take action and change his circumstances. Dilbert is never able to function as efficiently as he’d like because bureaucratic antics plague nearly every moment of his waking life. His company openly takes advantage of him, piling the hapless office dweller with menial tasks without the incentive of promotion or pay.

As a result, morale is perpetually low and company loyalty is essentially nonexistent. However, this does not stop Dilbert from always following orders, even when he knows they are riddled with obvious flaws. Though he’s supposedly a competent engineer that feels entitled to better hours, pay, and overall treatment, he never seeks out employment opportunities outside the misery of his own cubicle. At one point, Dilbert’s mother questions why he would work for a company managed by “despicable weasels”, and he lets the words of the higher-ups he so detests speak for him rather than evaluating his own actions.

On the rare occasion Dilbert is able to accomplish something, there’s negligible payoff because it seems that Dilbert’s anonymous company doesn’t actually seem to provide any good or service that’s actually helpful to the general public. He lives a Sisiphysian existence full of constant setback and struggle that never amounts to anything because he’s directionless and void of dreams.

Of course, it has to be this way. In order for readers to insert themself into the world of Dilbert, there can’t be too many details concerning the specifics of company objectives or the content of the meetings Dilbert shuffles between. He can never attain fulfillment, because if he did he’d stop being a voice for millions of disgruntled office workers that hate their jobs but feel trapped. Unfortunately for Dilbert, this means that he’s forced to live in a hellish world where he doesn’t know why he gets up and does what he does day after day.

If it ended there, Dilbert’s life would be tragic enough. But the sad truth is that, despite openly hating his job, he truly has nothing outside of his miserable work life.

For starters, Dilbert has no friends. Even Dilbert’s coworkers do not consider him a friend, canonically. He also has no family to speak of outside of his mother, who only appears on occasion but is consistently indifferent or critical of her son’s achievements. Dilbert does have a canine companion in the hyperintelligent, megalomaniac Dogbert2. But even Dogbert does not provide his master with the unconditional love characteristic of his species.

Though Dilbert enjoyed tinkering with inventions and playing intramural soccer early in the series, his passions ultimately faded away. On a total of two occasions, he mentions owning an Xbox, which presumably he enjoys using. However, this seems to cover the extent of Dilbert’s hobbies. So empty is Dilbert’s life that he often works entire weekends without extra pay in order to meet some arbitrary deadline. He hates taking vacations, in part because he worries about the work that he’ll have to make up while out of the office, in part because he knows that the time will be spent idly, alone in an empty house.

Unsurprisingly, Dilbert also struggles with romance. One might think that Dilbert’s socially awkward tendencies would repel women, and in some cases that’s true. But more often than not, he actually snags dates with eligible bachelorettes – only to immediately dump them over some perceived flaw. In spite of all the things wrong with Dilbert’s life, he consistently views himself as being out of any potential partner’s league.

This minor character trait reveals Dilbert’s most glaring defect, the core reason why misery defines his very existence. Above all else, Dilbert’s greatest need is to feel superior to others. The reason that Dilbert denies positive change at every opportunity is because he cannot tolerate the notion of not being the smartest person in the room. Nothing brings him greater joy than being right, even if that means suffering the consequences that come from everyone around him being wrong.

Dilbert would rather live an unsatisfied life in a toxic work environment than risk a future in which he’s not the voice of reason, where there might not be idiots that he can scoff at. Universally, anyone that disagrees with Dilbert is a moron. Any sort of change that compromises that reality is not even considered. Perhaps this is most clear to see in a Dilbert NFT Scott Adams has recently tried to peddle, in which the eponymous engineer utters the f-word3. What is it that ultimately inspires the titular character to use language too crass for the family-friendly funny pages? Dogbert gleefully proves a point to Dilbert, which upsets the latter so much so that he begins to tremble.

Of course, this haughtiness ultimately isolates Dilbert. He sucks at maintaining relationships with family, friends, and lovers because he is a pompous asshole. As much as he complains about his circumstances, he’s unwilling to jeopardize the pedestal he places himself on. And so, he finds contentedness in his discontent.

As mentioned earlier, Scott Adams spent his first sixteen years in the workforce toiling away at a job not unlike Dilbert’s. It was through these experiences that the first inklings of his critically acclaimed comic strip were born. In a 1999 interview, Adams estimated that “about 30%” of Dilbert’s character was based on Adams himself. So, where does Dilbert end and Adams begin?

Unlike Dilbert, Scott Adams broke away from the doldrums of office life shortly after he started his pursuits as a cartoonist. What’s more, there are layers of complexity to Adams that are lacking in the minimalist illustrations contained in each of his panels.

If you’re familiar with Scott Adams outside of his work on Dilbert, it’s likely because he’s become increasingly vocal concerning politics over the last several years. Unraveling what exactly those politics are, though, is a bit complicated. In the introduction to his book Win Bigly, he defines himself as an ultraliberal. He provides the following (surprising) example of how this ideology manifests:

Generally speaking, conservatives want to ban abortion while liberals want it to remain legal. I go one step further and say that men should sideline themselves from the question and follow the lead of women on the topic of reproductive health. (Men should still be in the conversation about their own money, of course.) Women take on most of the burden of human reproduction, including all of the workplace bias, and that includes even the women who don't plan to have kids. My personal sense of ethics says that the people who take the most responsibility for important societal outcomes should also have the strongest say. My male opinion on women's reproductive health options adds nothing to the quality of the decision. Women have it covered. The most credible laws on abortion are the ones that most women support. And when life-and-death issues are on the table, credibility is essential to the smooth operation of society. My opinion doesn't add credibility to the system. When I'm not useful, I like to stay out of the way. 4

Unlike most self-proclaimed liberals, though, Adams seems to have some degree of admiration for former president Donald Trump. The book from which the above excerpt is sourced primarily focuses on the businessman-turned-politician’s persuasive strengths. The cover features Dogbert sporting Trump’s trademark coif and spray tan. What’s more, Adams seems to have no aversion to chatting with far-right figureheads like Matt Gaetz or reposting headlines from questionable sources like Breitbart.

Where Adams ultimately falls on the political spectrum is almost beside the point, though. What’s more important in terms of understanding the man behind Dilbert is the ease with which he can and will broadcast his opinions, no matter how inflammatory they may be. For the last four years, Adams has uploaded daily 60-90 minute videos onto a Youtube channel titled Real Coffee with Scott Adams, in which he offers unfiltered thoughts on current events. It is not unusual for the cartoonist to make dozens of posts on Twitter per day. Most importantly, nearly every statement that escapes the inner workings of Adams’s mind is delivered with unshakable confidence that whatever he is saying is unequivocally true.

(If you appreciate works like this but aren’t necessarily interested in upgrading to a paid subscription, please consider buying me a coffee – this series didn’t write itself!)

This is where the commonalities between creator and creation begin to become evident. Just like Dilbert, Scott Adams has a need to be (or, at least, perceive himself to be) the smartest man in the room at any given time.

If you were to sneak a peak at Scott’s Twitter profile, you’d be greeted with a bio claiming Adams was the “#1 best predictor in the country during the pandemic”5. You wouldn’t have to scroll through the backlog of declarations for long to find Adams bragging about his 2015 prediction that Donald Trump would win the 2016 presidential election. Though he’s best known for his comic contributions, he’s dabbled in self-help entirely divorced from the world of Dilbert and has even authored two theologically-themed novellas that quite literally revolve around the smartest man in the world. It is no secret that Adams takes immense pleasure and pride in being right, regardless of what the topic at hand happens to be.

However, there is never any back and forth concerning any of Adams’s overarching statements, never an opportunity to counteract a claim6. Whether it’s on Twitter or Youtube or in your local newspaper, Adams talks at his audience rather than with them7.

Even on the rare occasion that a critique or correction or comment gets through, anything that contradicts the artist’s worldview is generally not even entertained. For instance, Norman Solomon’s 1998 publication The Trouble with Dilbert: How Corporate Culture Gets the Last Laugh brought up a valid point against the comic. According to Solomon, despite all the jabs the series makes at stupid bosses and inefficient policies, Dilbert and his co-worker’s inaction ultimately breeds real-life complacency for inadequate work conditions by constantly sending a message that workers have no power against corporate overlords. Yet, when confronted with Solomon’s claim, Adams simply shrugged and stated that Solomon lacked a sense of humor, implying that his critic was looking too much into a simple cartoon. Any acknowledgment that Adams might be wrong or inaccurate or unaware is always pushed aside rather than addressed.

Throughout his philosophically-fueled novella God’s Debris, Adams refers to the human mind as a “delusion generator”, and denouncing naysayers as delusional seems to be a go-to tactic for Dilbert’s dad. Perhaps critics are never allowed a word in edgewise to maintain Adams’s own self-aggrandizing delusions.

The single most impressive thing about Adams is the sheer amount of content he’s managed to churn out over the course of his career. As much as one should avoid making presumptions about others based solely on their carefully curated online activity, it’s impossible to avoid feeling like you know Scott Adams a little bit after so many hours of sifting through his thoughts and hearing his opinions aloud. The bravado with which he delivers controversial statements and the sarcasm that drips off of everything from his frequent Tweets to his daily comics surely offer some insight. Putting the fragments together, this much is evident: Scott Adams is deeply frustrated. At the US government. At the invisible woke masses. At just about anyone or anything that stands counter to his worldview.

And underneath all of that is profound loneliness – the kind only a genius in a world full of idiots could possibly understand.

Perhaps the curse both the hapless office worker and the famous cartoonist face day-in and day-out is best encapsulated in one of the franchise’s greatest failures, the Dilberito.

The first reference I could find of this venture was at the tail-end of the same 1999 interview mentioned earlier. Adams enthusiastically closes his encounter with journalist Charlie Rose by announcing that Dilbert will soon be taking on a new frontier in the food industry. Initially, I thought that this was some sort of absurd joke cloaked in Adams’s characteristic sarcasm. But a little digging revealed that the Dilberito did exist and was exactly what it sounded like – a Dilbert-branded burrito.

As a longtime vegetarian with a hectic schedule, for many years Adams struggled to find meal options that were both low-effort and health-conscious. So, he aimed to create what he called “the blue jeans of food” – that is, something that people could eat every single day without putting much thought into the matter. In theory, the Dilberito was meant to fulfill 100% of a person’s recommended daily value for “23 essential vitamins and minerals”. Using the existing Dilbert branding, the product was specifically targeted at people so busy with their work that they lacked the time to take a break and enjoy a proper meal.

Though not a meal replacement per se, the ideas driving the Dilberito aren’t unlike those that later inspired meal replacements like Soylent. Both view the act of eating as an engineering problem rather than something to be enjoyed. To fuel oneself is a time-consuming inconvenience that takes away from productivity, and both Soylent and the Dilberito were created with the intent of solving hunger as efficiently as possible. The Dilberito fulfilled one’s nutritional requirements without superfluous fat or cholesterol or sugar, making it a largely “correct” choice when strictly viewing food as nourishment.

Of course, the vast majority of people do not make dietary decisions based strictly on nutrition alone. We’re strongly influenced by taste and texture, by the way food makes us feel. Unfortunately, the Dilberito supposedly didn’t take those aspects into consideration at all. A 1999 New York Times review describes the concoction as “a vitamin pill wrapped in a tortilla” and something that “could have been designed only by a food technologist or by someone who eats lunch without much thought to taste”. In his book How to Fail at Almost Everything and Still Win Big, Scott Adams himself claimed that “three bites of the Dilberito made you fart so hard your intestines formed a tail”. Because the Dilberito sucked the soul out of food, it was a commercial failure that was pulled from store shelves by 2003.

In a March 2021 episode of Real Coffee, Scott Adams blamed the fiasco on the fact that the initial taste-testers kept the gastrointestinal distress they felt after eating the prototypes to themselves. But beyond that, Adams missed (or chose to ignore) the glaring flaw present in the Dilberito from the get-go: that it, by all accounts, didn’t taste good. As a vessel for vitamins and minerals, the product was perfectly formulated. But as true as that may be, as soon as you expand beyond that singular metric, all you’re left with is an unknown number of microwave burritos thrown into the trash after a single bite or left in the back of freezers to accumulate ice indefinitely.

These same pitfalls plague both Dilbert and Scott Adams outside the realm of food, too. Dilbert seeks satisfaction in his life by approaching every issue that comes his way with the mind of a methodical engineer that already knows everything worth knowing. But in the process of addressing whatever the problem at hand is cold and analytically – whether it’s writing up a report or securing a second date – he fails to consider the human elements involved. There’s never any consideration for how his girlfriend might react to the rude comment on the tip of his tongue. It never occurs to Dilbert to take a leap of faith and leave the job he detests because stagnating in his own superiority is more comfortable. Dilbert cannot imagine a scenario in which his methodology is incorrect, so he never overcomes his shortcomings and instead blames everyone else for his suffering.

Ultimately, Scott Adams is cut from the exact same cloth. He is wrong about an awful lot. He either cannot or will not take into account the immeasurable factor of human emotion when deciding what words will fill the thought bubbles of his creations or populate his social media timeline. The Dilbert-verse is becoming increasingly political because Adams himself struggles to perceive a reality where there’s more worth learning about trans issues or mass shootings or substance abuse. In the comfortable cesspool of his mind, Adams is always right. Because of this, he will continue to be wrong about a lot of things for the foreseeable future.

And inevitably, this will be what leads to the downfall of Dilbert.

I’m not really sure what the purpose of this move was on the publisher’s part, since changing Dave’s skin tone doesn’t cancel out the gender/pronoun joke that would hypothetically be the thing that would piss readers off. The original version of the comic can be found in the dilbert.com archives.

Fun fact: Dogbert’s name was initially slated to be “Dildog”. For real.

Much to the cartoonist’s disappointment, the listing for the Dilbert F-word NFT had zero offers as of the publish date of this article

Interestingly for the sheer amount of opinions he broadcasts on a daily basis, I could not find a single statement from Adams concerning the recent overturning of Roe v. Wade outside of it being “a huge victory for oral sex”.

I don’t know by what metric Scott Adams makes this claim so please don’t ask me.

Technically, I’m not being entirely accurate. Though Real Coffee does feature a live chat function, Adams only seems to respond to it when there’s a specific question or an explicitly positive comment. The same could be said for his Twitter replies. I’d still argue, however, that allowing the audience the power to respond is a very different thing from actively engaging in conversation or showing any willingness to grow.

There’s a certain irony to this that’s not lost on me, considering Dilbert’s origins and the heavy hand early readers played in shaping the direction of the cartoon.

Really cool how you gave such a character assessment of Dilbert and Adams.

It is interesting to read this now. Guess you were right. He did more than just trying to get canceled...

In the evolution of his comics over the past couple years (in his recycling of lame Babylon Bee headlines), he can be seen slowly driven insane by the right-wing media making him think

"woke" culture is the biggest threats in the world. Some small amount of people, who are associated with progressive politics, use a word or phrase that seems strange to him and annoys him. The right-wing media keeps telling him people like him are getting canceled, so he gets scared of being canceled. Then Rasmussen tells him: black people hate white people!!! And he believes their garbage. ... So it was ultimately right-wing media that got him canceled. ... It shows how poisonous that stuff is even to the people who consume it and believe it.

Meghan, I love going down your rabbit holes. TY