When Peter Pan Grew Up

Reflecting on the tragic child star who became one of Disney's darkest secrets.

The world portrayed in the recently released Chip ‘n’ Dale: Rescue Rangers movie is a particularly dark and cynical one. This may come as a shock, considering that the stars are two adorable cartoon rodents voiced by popular comedians John Mulaney and Andy Samberg. Even so, it quickly becomes apparent that their universe is more sinister than the technicolor surroundings might imply.

Finding out at the start of the film that Chip and Dale had a professional falling out, hadn’t spoken to one another in over three decades, and ultimately lived pretty lonely and unfulfilling lives well into their 40s was pretty tragic in itself. Watching their former co-star Monterey Jack lapse into a “cheese” addiction that he can’t afford and subsequently get abducted by his disgruntled dealers also seemed like an unusually bleak choice for a children’s movie. Learning that Monterey Jack would be “bootlegged”1, it was really difficult not to draw parallels to very real human trafficking practices that often result in victims being forced into labor.

But the plot point that really floored me most was when the antagonist “Sweet Pete” was introduced. Before seeing his face, we learn that Sweet Pete is essentially the leader of a heinous crime syndicate that slings everything from illicit substances to cartoon slaves. This makes it all the more shocking when it is revealed that Sweet Pete is actually none other than a washed-up Peter Pan.

Now, Peter Pan is far from the film’s only cartoon cameo – there are literally dozens. Even so, Peter is done particularly dirty and transformed into an unrecognizable, unsympathetic character. He has heavy bags under his eyes, suffers from a receding hairline, and (inexplicably) has the grizzled voice of a mafioso. Almost immediately, he commands his lackeys to capture the chipmunks, and toward the end of the film tries his damndest to actually murder them.

For the casual viewer, this Peter-as-villain twist is kind of funny in a sick way. When childhood fantasies can’t last forever, it becomes easy – understandable even – to become bitter. But Peter’s portrayal immediately triggered a small but significant outcry from a few critics. The reason? Unlike your average antagonist, the backstory of this grotesque caricature seems to be (at least partially) modeled after real events experienced by a real person.

The name Bobby Driscoll likely doesn’t mean much to even the most dedicated Disney fanatics of today. But at one time, he was the franchise’s darling, the literal prototype for Peter Pan. And for the few that do remember him, it seems clear that the Chip ‘n’ Dale’s antagonist (to some degree) mocks the memory of the former child star. To understand Bobby’s full story in all of its tragedy – from start to Sweet Pete – is to understand Disney at its most callous.

Before there was Peter Pan, there was Bobby Driscoll.

For the first five or six years, Bobby’s life was pretty typical for a young kid growing up in the 1940s. He was born in Des Moines and had he stayed in Iowa, he likely would have lived an unremarkable, but mostly content, life. Unfortunately, a doctor suggested that Bobby’s father, who suffered from asbestos-related health problems, might benefit from a move to California. So just like that, the family relocated to Los Angeles.

Almost immediately, Bobby Driscoll caught Hollywood’s attention. “That kid ought to be in the movies,” commented the child’s barber one fateful day. Likely to the Driscoll’s surprise, the barber then proceeded to use his personal connections to snag Bobby an audition at MGM. His impish upturned nose and smattering of freckles certainly gave him the right look for show business. But there are seemingly endless streams of cute kids to be found on a Hollywood casting call. What differentiated Bobby Driscoll from the others was his magnetism. His inquisitive nature and genial smile were ultimately the factors that allowed him to stand out amongst dozens of other children.

As soon as Driscoll made his initial film debut in 1943, he was able to secure a steady stream of roles that fell under the general “precocious little boy” umbrella. But Bobby’s stardom would skyrocket in 1946, when he caught the eye of none other than the legendary Walt Disney.

To sidetrack for just a moment, at this point in time Disney had primarily focused on the hand-drawn animated films that we’re most familiar with today. Features like Snow White and the Seven Dwarves, Pinocchio, Fantasia, and Dumbo had garnered a tremendous amount of praise, and even in its infancy Walt Disney Productions proved to be a force to be reckoned with. But the 1940s proved to be some of Disney’s darkest hours, at least from a corporate perspective. Bobby’s arrival came at a pivotal moment for the still-fragile studio.

In 1941, inequalities in pay and privilege between the artists working for Walt culminated in a particularly acrimonious animator’s strike. Though it ended with Disney signing a union contract, the studio ultimately lost nearly half of its employees. The following year Bambi (in spite of its contemporary popularity) received initial reviews that ranged from lukewarm to almost vitriolic. As if that weren’t damaging enough, the US government essentially commandeered Disney’s operations and forced them to churn out pro-war propaganda in the thick of WWII. Whether or not the occasionally-racist morale boosters actually accomplished their goal, they generally didn’t generate a significant profit. When the war finally came to an end in 1945, Disney could no longer afford to fail.

Because of the aforementioned troubles, Disney began experimenting with anthologies that utilized live-action footage interspersed with animation. Because producing animation was the most expensive part of previous productions, this hybrid approach allowed Disney to create films on a much tighter budget.

All the studio really needed was a few charismatic kids to bring this concept to life. And in Walt’s eyes, Bobby was the perfect candidate to represent his emerging brand.

Driscoll made his Disney debut starring in 1946’s Song of the South. Even in the very different political landscape of 80 years ago, the film was controversial among audiences because of its blatant romanticization of life on a southern plantation2. Due to public outcry over the years, Song of the South has never been made available for home video distribution in the United States, and you certainly will not find it streaming on Disney+. All the same, one thing was agreed upon despite the contention surrounding the film – that the live-action performances were exceptional.

Though Song of the South has largely been buried, the phenomenal acting from Bobby and co-star Luana Patten earned them the distinction of becoming the first actors to sign a long-term contract with Disney. Marketed as the ‘sweetheart team’, the two appeared together again in another feature titled So Dear to my Heart. “So Dear was especially close to me,” Walt once commented, “Why, that’s the life my brother and I grew up with as kids out in Missouri.“

The aspects that drew Walt Disney to So Dear were likely the same ones that motivated him to model Disneyland’s Main Street USA after the main street in his childhood home of Marceline, MO. Both are insular, highly idealized universes, only made possible when you are willfully blind to societal hardships and tune out the cries of neighbors failed by promises of the American Dream. Bobby didn’t just look the part of a child that could exist in such a place. When he set his mind to it, Bobby Driscoll could turn his eyes into portals tethered directly to his heart. Ultimately, he could convince a person that the imaginary realm he existed in was attainable and just as beautiful as it seemed on the big screen.

Unfortunately, when the cameras stopped rolling, Bobby’s life wasn’t quite as idyllic as the pictures portrayed. His relationship with his parents was complicated at best. Although it seems that he loved and cared for his mother and father throughout the course of his life, a 1995 interview with fellow child star Russ Tamblyn revealed that Driscoll’s childhood was fraught with abuse. “His father used to whack him around a lot," Tamblyn explains before describing an incident in which Bobby’s parents locked him in a closet overnight. At one point, Disney Studios allegedly moved Bobby in for a time with his co-star Luana Patten and her family, suggesting that his employers were well aware of his mistreatment at home.

What’s more, Bobby’s stringent work schedule largely isolated him and proved to be a major obstacle in forming healthy relationships with children his own age. Instead of playing outside or socializing with others, the young actor spent much of his time at home memorizing lines. “I wish I could say that my childhood was a happy one, but I wouldn’t be honest,” Driscoll admits in a 1961 interview, “I was lonely most of the time”.

As much as it hindered Bobby Driscoll’s personal growth, this dedication to his craft was ultimately what catapulted the boy into momentary greatness as he matured. In 1949, he was given the opportunity to prove that he was more than an all-American Disney kid when the studio “loaned” him to RKO for the thriller The Window. So convincing was his performance as a haunted murder witness that he easily outshined his (quite talented) adult co-stars. At the 1950 Academy Awards, he was presented with an honorary “Outstanding Juvenile Actor” recognition by the film industry. Just twelve individuals have earned this title over the course of the Academy’s history, among which are screen legends including Shirley Temple, Judy Garland, and Mickey Rooney.

A few years later came the performance Driscoll is best remembered for, the titular role in Peter Pan. When you watch the Disney classic, it’s Bobby’s voice that you’re hearing. But it doesn’t just end there. Bobby Driscoll was also the live-action reference model for the movie’s close-up shots (though dancer Roland Dupree was used for many of the flying and action sequences). When you picture Peter Pan, Bobby’s face is the one your mind will conjure. In those last few perfect moments of boyhood, Peter and Bobby were one and the same.

Unfortunately, one thing separated the actor and the 1953 animated character – Bobby didn’t have the luxury of staying a boy forever. And the moment Driscoll could no longer be shoehorned into the role of a child too perfect to actually exist, life took a drastic turn for the worse.

“I had never been so happy in my entire life. Then I got older, and they threw me away like I was nothing,” the haggard old Peter we see in Chip ‘n’ Dale laments. This line, in particular, brings to mind a sentiment Bobby Driscoll expressed toward the end of his life: “I was carried on a silver platter and then dumped into the garbage can”.

Just weeks after the release of Peter Pan, Bobby Driscoll’s contract with Disney was terminated without warning, years before it was scheduled to expire. The official reasoning? Severe teenage-onset acne had blemished his once-beloved face. Some rumors claim that no one even bothered to reach out to let him know that he had been fired. Instead, he was turned away from the studio when he arrived for work one day. Regardless of how exactly the events panned out, this was a devastating blow for Bobby, who had always responded obediently to the often unreasonable demands of the adults that controlled his life.

He was suddenly thrust into the hell that is public high school as a sophomore, and immediately he struggled. His new peers mercilessly bullied him, and he only found solace with other troubled outcasts. Within months of leaving Disney behind, he began experimenting with marijuana and quickly escalated to heavier drugs.

Initially, he was hopeful that his career might kick back up after exiting his awkward teen years. He moved out to Manhattan and trained in the Actor’s Studio under the great Lee Strasberg. But his struggle to consistently land roles was one that even his great talent could not overcome. People ultimately recognized him as Peter Pan, as the happy-go-lucky kid that sang "Zip-A-Dee-Doo-Dah” alongside James Baskett’s Uncle Remus. And that was not what many casting directors wanted starring in their serious lead roles. As this became increasingly clear, Bobby became more reliant on narcotics. This eventually led to the first of several drug possession charges, which effectively made Bobby a professional pariah. “Hard-luck stories in the movie colony are a dime a dozen. But oblivion at nineteen. I couldn’t quite believe,” reporter Andrea Sheridan published in 1956 in regard to Driscoll’s plight.

That same year, Bobby met and married a girl named Marilyn. According to him, the two primarily connected over being lonely. Within three years, the couple had three children. But Marilyn suffered from schizophrenia, and the money Bobby brought in from odd acting jobs and a part-time gig at a haberdashery wasn’t enough to support a family. Combined with increasingly frequent run-ins with the law, the family fell apart. After spending time in and out of rehab and jail, he relocated to New York City in his late 20s.

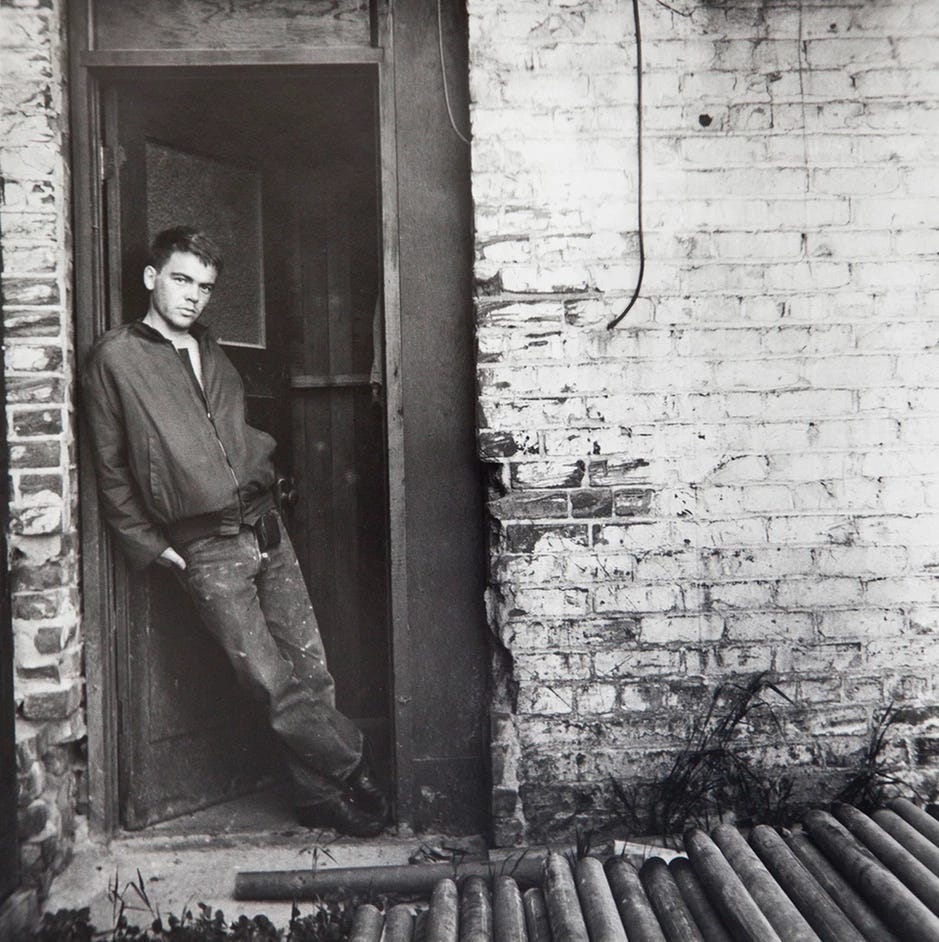

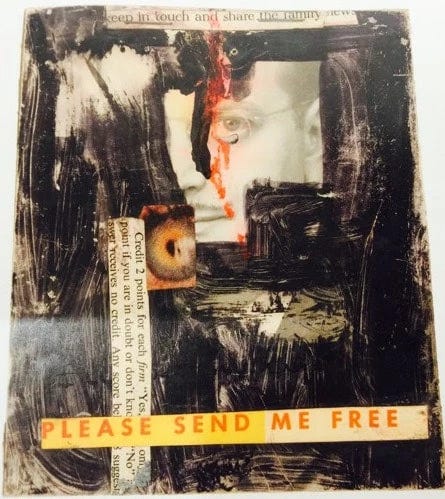

If there was one thing that brought Bobby solace, it was art. As early as age 18, he began associating with some of the most prominent figures of the Beat Generation. A sensitive intellectual in constant search of connection and deeper meaning, the Avant-Garde community of the time was the closest to accepting Driscoll for the person he actually was. In particular, he developed a close friendship with experimental filmmaker Wallace Berman, who encouraged him to dabble in photo collage and poetry.

Keeping this in mind, it will come as a bit less of a surprise to learn that Bobby struck up a relationship with Andy Warhol when he moved to the east coast. For a time, he was a frequent fixture hanging around Warhol’s silver-clad, uber-hip Midtown studio. He wasn’t necessarily a perfect fit among the in-crowd, but he seemed to enjoy having an outlet and felt inspired to be in the company of other creative minds.

Until one day, he just stopped showing up. By 1968, Bobby’s friends and family lost contact with him, and evidently, The Factory denizens were too absorbed in their own affairs to look into Bobby’s whereabouts.

Bobby’s final days were murky. Some claim that he was attempting to kick his now-voracious heroin addiction. Others claim he had started seeking solace in Christianity. All that we know for sure is that two children playing in an abandoned Greenwich Village tenement stumbled upon the former actor’s body among a heap of beer bottles and religious pamphlets. Coroners later determined that at the age of thirty-one, Bobby had died due to hardening of the arteries resulting from years of intravenous drug abuse.

No one – not even his mother – claimed his body. Eventually, he was buried at Hart Island, the potter’s field that serves New York City. The greater public didn’t learn of his demise until 1972, when he failed to appear for a rerelease of Song of the South.

Of course, the reinvented Rescue Rangers Peter Pan is not a perfect parallel to Bobby Driscoll. After all, Bobby didn’t live long enough to become so depraved. In the few interviews of his that survive, he was witty and thoughtful. Excluding an incident with a pea shooter as a teen and a run-in with a heckler, all of his crimes were victimless. I can say with confidence that he was never a villain, let alone a one-dimensional villain totally unworthy of sympathy.

All the same, the similarities are unmistakable. During Pan’s evil origin story, they gave him the acne scars that got his real-life counterpart fired all of those years ago. There is no redemption or dignity for him, and the movie ends with Peter locked away in some sort of maximum-security solitary confinement, alone and muzzled Hannibal Lecter-style. And most importantly, as soon as Disney stopped caring for both Peter and Driscoll, the rest of the world followed suit.

If anything, Disney is intentional. It is evident when you go to one of their meticulously manicured theme parks, or when you spot a carefully-placed easter egg in the background of your favorite Pixar film. They do not make careless mistakes. So why create this weirdly insensitive, mostly unnecessary3 villain for the sake of a direct-to-streaming Chip ‘n’ Dale reboot?

The only reason I can come up with is this: Bobby’s countless wounds, self-inflicted or otherwise, were not enough to atone for the sin of growing up into something less than perfect. Decades after his passing, memories of him have almost entirely faded from public memory. But Disney actively made a choice to resurrect their former sweetheart – only to reiterate how disposable he was.

Special thanks to Jessi of the Remembering Bobby blog as well as the moderator(s) of bobbydriscoll.com, who have archived a variety of materials documenting Driscoll’s life.

In the film, this entails physically altering the victim’s appearance via nonconsensual surgery and then sending them “overseas” to star in bootleg Disney films against their will. There’s probably something to be said concerning the fact that this film implies that violating copyright law and stealing intellectual property is akin to human trafficking, but I’m not going to attempt to fully unpack that here.

I’m specifically phrasing this way because while the film canonically is supposed to take place during the Reconstruction Era following the Civil War, any clear indication that the African Americans featured in Song of the South were explicitly not slaves was left on the cutting room floor. I’m not really sure that it matters because even if the people working the plantation were sharecroppers it completely disregards the desperate situations that led freedmen to pursue sharecropping in the first place. If you really want to determine for yourself how problematic the film may or may not be, it’s available to watch on archive.org.

You can make the argument that the washed-up Peter Pan narrative serves as a parallel to Chip and Dale’s career failures following their “break up”, but even so there are definitely ways that they could have conveyed this idea without alluding so heavily to Bobby Driscoll’s struggles.