Enter Hatman: Exploring the World of Benadryl-Induced Delirium

A little essay on the most demented drug sitting in most people's medicine closet.

In April, a 13-year-old boy from Colombus, Ohio accidentally overdosed on over-the-counter Benadryl tablets. Shortly after ingesting the little pink pills most commonly used to treat allergen-induced runny noses and rashes, the teenager’s body began to seize in front of a handful of his horrified friends. After spending six harrowing days on a hospital ventilator, the boy died.

According to reports, the severe reaction experienced by the boy – his name was Jacob Stevens – was not from some freak allergic reaction that couldn’t be avoided. Instead, he got the initial idea to load up on antihistamines from a “new” TikTok trend called the Benadryl Challenge. I say new in quotes because the Benadryl Challenge has actually existed (at least to some extent) for several years at this point. Back in 2020, a fifteen-year-old Oklahoma teenager allegedly died under a set of nearly identical circumstances. Sporadically since, local news outlets and medical journals alike have published accounts of young people administered to hospitals in dire conditions after reportedly encountering and accepting the challenge, each time claiming that it was the latest trend to spread like wildfire among bored teenagers.

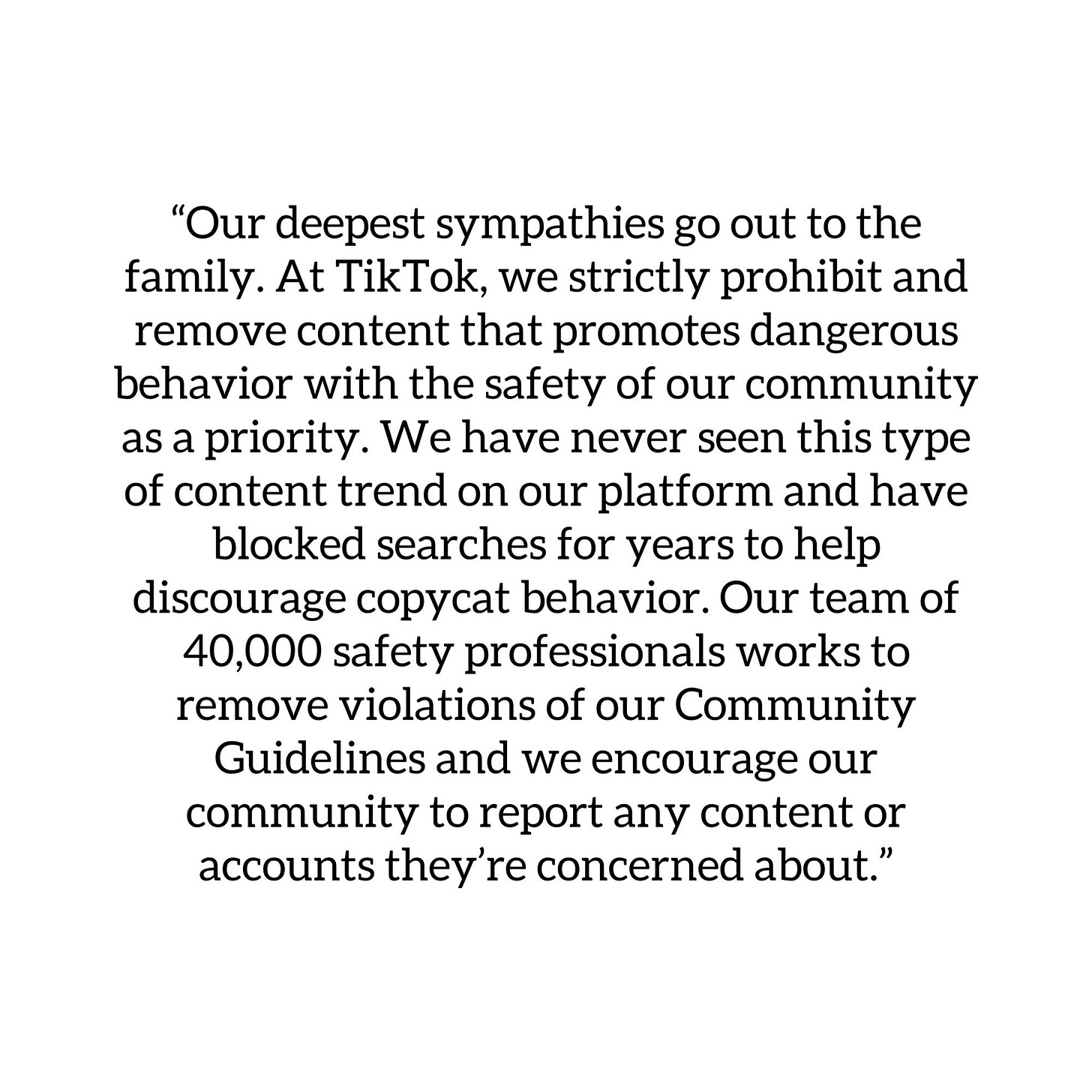

TikTok released the following statement in response to Jacob’s death:

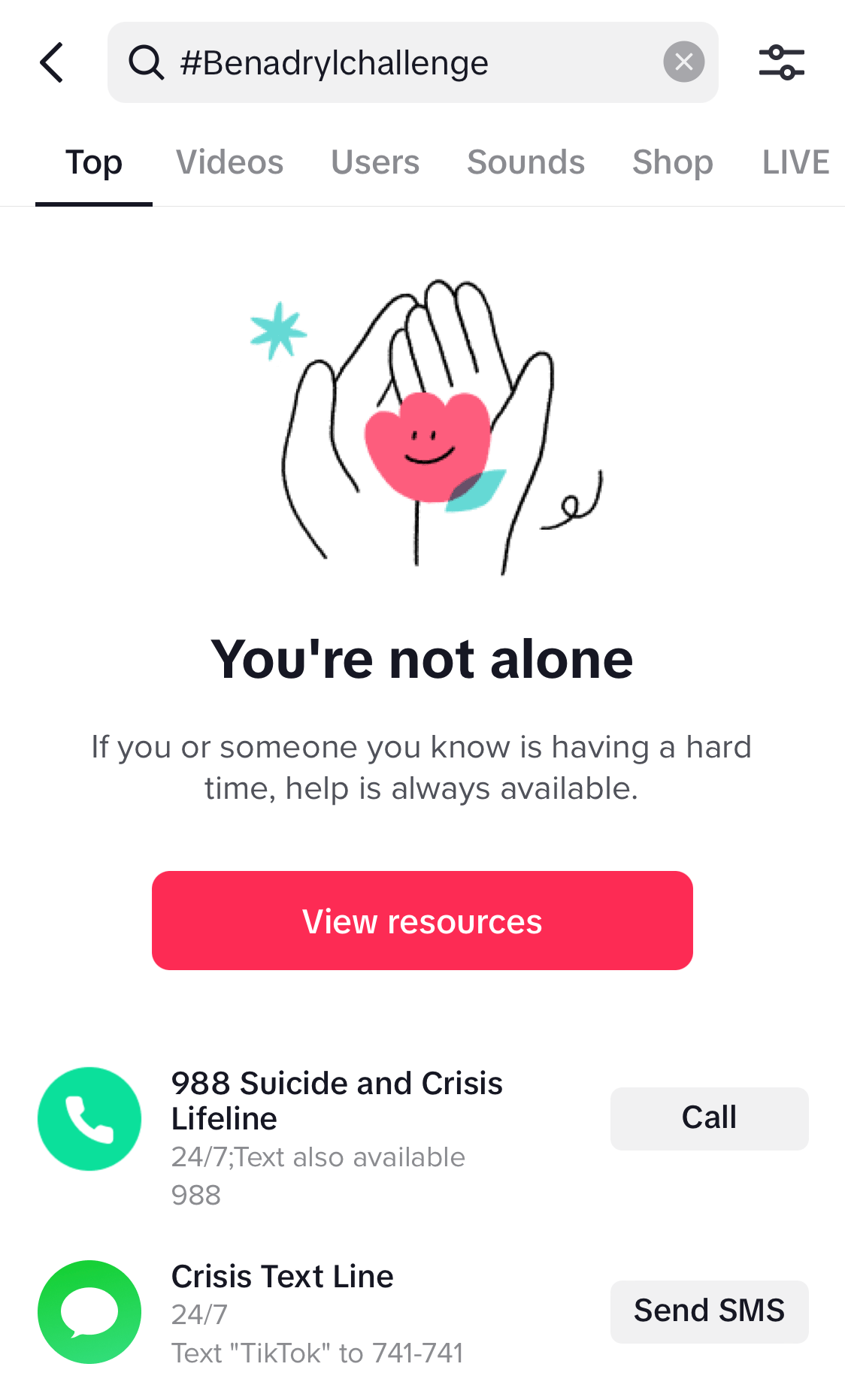

Indeed, it’s extremely difficult to tell how widespread the “viral” challenge ever was on TikTok as the platform has blocked hashtags pertaining to it since 2020. Contrary to what online outlets that profit off of the fear-fueled clicking of paranoid parents might have you believe, searches on platforms like Youtube and Instagram also fail to generate clips of kids shoveling Benadryl into their mouths.

Taking all of these factors into account, one might conclude that the supposed Benadryl Challenge never existed to the extent that media outlets reported1. After all, the only evidence that seems to suggest that the challenge was ever rampant lies largely in the occasional slapdash report or stray Facebook mourner’s testimonial, neither of which seem to have a firm grasp of the mechanisms and contents that drive platforms like TikTok.

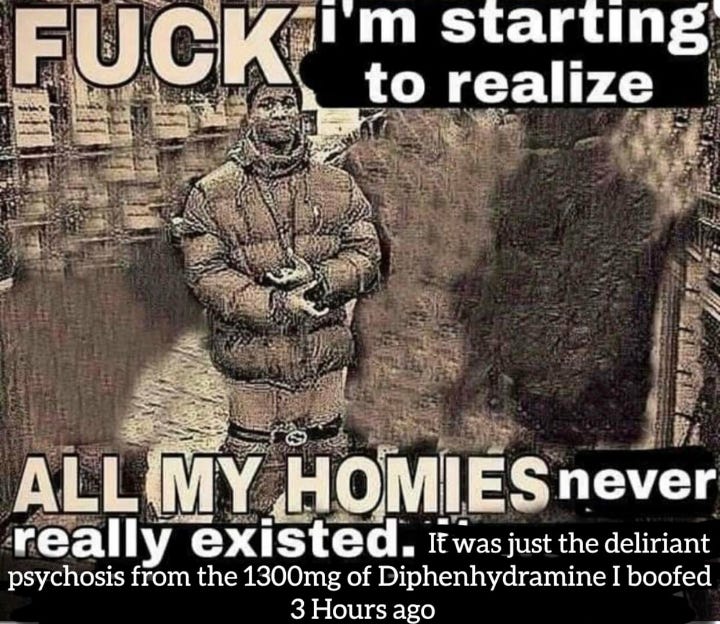

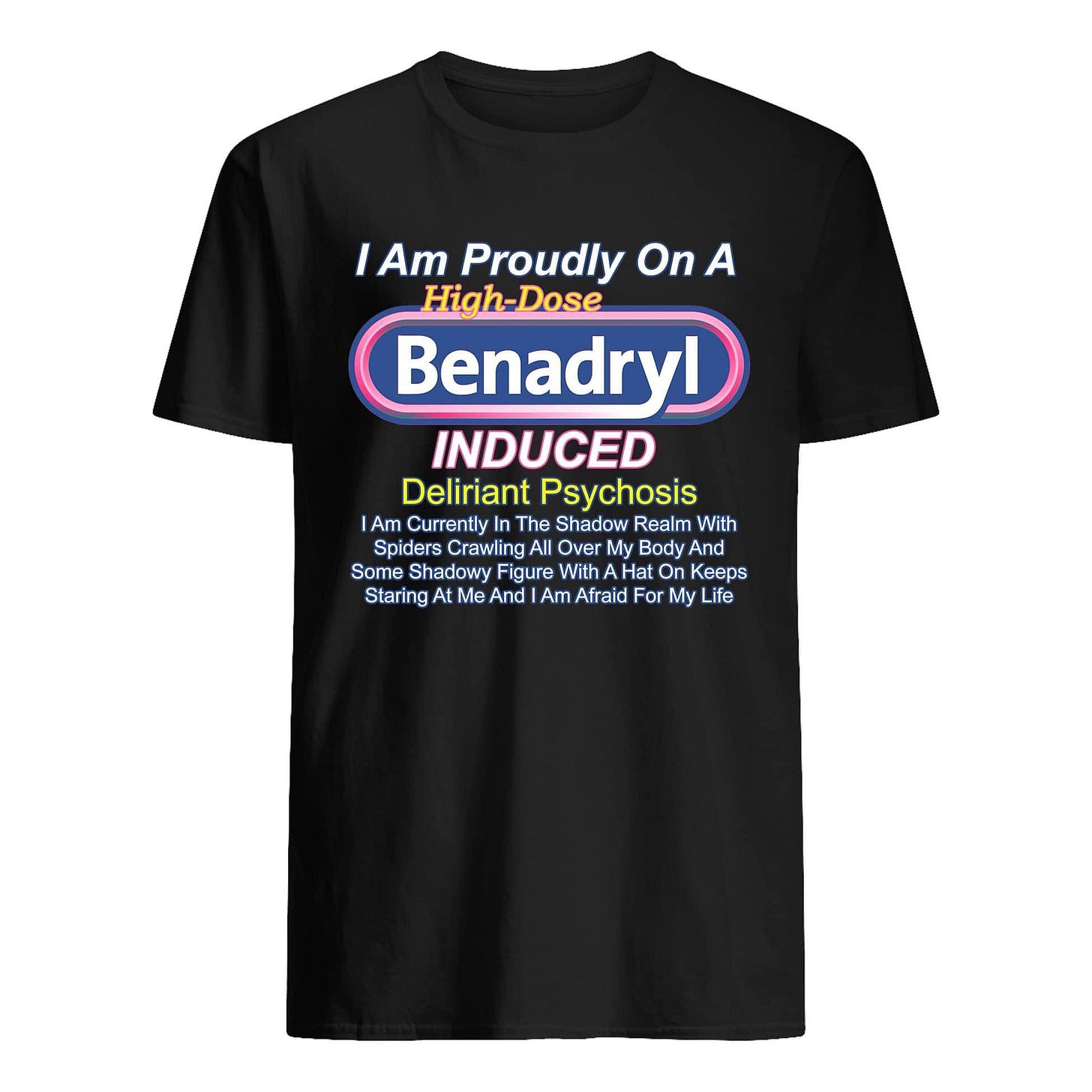

But to trick oneself into thinking that Benadryl doesn’t fascinate impressionable individuals with unfettered internet access would be entirely inaccurate. Though the Benadryl Challenge itself may not be widespread, evidence suggests that diphenhydramine (the active ingredient in Benadryl2 and Benadryl-like substances, also referred to as DPH) abuse long predates any alleged TikTok trend3. The self-identified psychonauts of Erowid’s online community have been experimenting and sharing experiences with the drug since at least the early 00s. Nine years ago r/DPH appeared on Reddit, where it now enjoys a 50,000-member following. You won’t find videos of friends egging each other on to ingest allergy medications that fit the mold of traditional internet “challenge” videos there. You will, however, encounter still images featuring mounds of pink pills, and hundreds of diphenhydramine-inspired memes that look something like this:

As a rule, these memes are strange and dark, both thematically and literally. They speak of spiders and shadows and “the Hatman”, a menacing and mysterious figure who brings to mind memories of the Slenderman horror stories of the early 2010s4. Images often utilize glitchy aesthetics, revering the degradation in the artifacts of infinitely recirculated JPEG files. In his 2003 essay Welcome to Cyberia, art theorist and historian Michael Betancourt had the following to say on the subject of glitch art:

“The glitch is the transient failing, the momentary lapse that allows us to see underneath the mask at the reality hidden inside the digital representation: How much data has been lost to faulty storage, poor transmission, or obsolete technology? […] The glitch shows us the screen, not our fantasy displayed upon it.”

Betancourt’s musings are entirely divorced from the topics of drug abuse or 21st-century meme culture. Even so, his words unintentionally begin to touch on what’s missing from virtually all coverage of the “emerging” dangers5 of Benadryl. Chalking up diphenhydramine use as a passing social media fad is both inaccurate and does nothing to explain the actual reasons why people have been driven to stomach large doses of it for decades.

DPH is not something users consume to get laughs or views. Those that decide to swallow dozens of Benadryl have entirely different intentions than, say, influencers tackling the Cinnamon Challenge, boasting of epic failures between hacking coughs. Nor is it something that kids do to feel good, as a significant percentage of users describe feeling physically horrible both during and after Benadryl highs.

Instead, the appeal of DPH lies in its unique ability to send people to a realm where the glitch reigns supreme and perception of reality begins to crack. The world becomes the Hatman’s playground, where fiction becomes indisputable truth and surroundings morph into something undeniably fascinating and immeasurably frightening all at once.

(If you appreciate works like this but aren’t necessarily interested in upgrading to a paid subscription, please consider buying me a coffee – this series didn’t write itself!)

If you want to understand why some people risk life and limb on this over-the-counter medication, there’s only one thing you need to know: the high that comes from DPH is unlike anything else out there.

This is because DPH – the same drug that millions use to combat pet dander and pollen, the drug that mothers will give fussy babies to sleep on airplanes – is a special type of hallucinogen called a deliriant. Its effects, both physiologically and psychologically, are vastly different from those produced by psychedelics (like LSD) and dissociative drugs (like Ketamine). For the most part, those that indulge in more “traditional” hallucinogens at moderate dosages are able to retain full functionality and awareness of the illusory nature of their altered perceptions. Deliriants, on the other hand, create hallucinations in the truest form, entirely indistinguishable from reality.

But perception isn’t the only thing that’s impacted during a DPH trip. In recommended doses, DPH prevents messages from transmitting to the body’s histamine receptors. Histamine is the chemical your immune system releases when it detects an irritant, which consequently triggers inflammation, runny nose, diarrhea, or whatever is deemed necessary to flush out the perceived irritant. But in the brain, histamine also plays a major role in regulating wakefulness, memory, and attention (which is why Benadryl is also used as a sleep aid). When all of the brain’s histamine receptors are bound and can no longer receive messages, short-term memory loss and full-blown delirium can occur.

Worse still, when you take a large dose of Benadryl and it plugs up all of the body’s histamine receptors, the excess DPH will begin to target acetylcholine receptors instead. Acetylcholine has a number of functions in the body, not all of which are yet fully understood. It’s particularly vital at neuromuscular junctions, where it transmits messages from the brain to activate muscles and allow movement throughout the body. Acetylcholine is also the chief neurotransmitter in charge of stimulating the parasympathetic nervous system, which regulates unconcious activities such as sexual arousal and digestion.

Acetylcholine has also been shown to be vital in the brain’s ability to form new memories and generally intake new information. One study on Rhesus monkeys has shown that in high enough doses, anticholinergic drugs can result in forgetfulness comparable to anterograde amnesia. For years, researchers have linked high cumulative use of anticholinergic drugs to increased risks of Alzheimer’s disease and dementia. Furthermore, the cognitive side effects of antihistamines could potentially be amplified when the brain’s acetylcholine receptors are also blocked.

So how do all of those factors manifest, exactly, after you’ve swallowed a couple of dozen Benadryl?

At the start, it’s often not so bad. Erowid users authoring anecdotes often recall feeling as if they’re in a dream. According to their accounts, it’s not unusual to feel tranquil, perhaps even euphoric. Some claim to experience a delay or disconnect in the wires between their brains and bodies, making movement increasingly difficult. But even as limbs grow heavy and simple tasks like walking require increased concentration, it’s not yet particularly unpleasant.

But with the parasympathetic nervous system’s ability to rest and digest temporarily defunct, most people lose the ability to salivate and report developing a dry mouth. This is often accompanied by significant difficulty when using the bathroom. Some people report feeling nausea as gaits become unsteady and vision begins to blur.

Tremors and muscle spasms are common occurrences, and those accustomed to taking large doses may even experience seizures. Many write-ups describe intense heart palpitations, and arrhythmia becomes a major concern as blood pressure decreases and the heart is forced to beat faster. A 15-year-old boy described the sensation as being “like a machine gun was going off in my chest” in a 2018 trip report titled “Hell on Earth”.

As all of these physical symptoms set in, people enter states of delirium. Short-term memory loss is common, and some people forget that they’ve taken a drug at all. Perhaps the scariest side effects of all are the visual and auditory hallucinations. What those hallucinations may be, exactly, depends on the individual. And unlike the physical symptoms listed above – which can be explained by examining the pharmacology of the drugs – imaginary visions and voices are something incapable of being fully rationalized.

“The walls were breathing a little, and dark colors were shifting […] I saw little rips in the fabric of our very reality,” one Erowid post states. People frequently recall full-blown conversations with friends and family members that aren’t actually there. Time and time again, insects seem to spontaneously spawn. A 30-year-old man recalled spending an evening squishing imaginary fleas, mites, and spiders with wadded-up toilet paper after ingesting 725mg of diphenhydramine.

And of course, there’s the Hatman.

Not every Benadryl trip entails a visit from the Hatman, but many people claim to encounter menacing men shrouded in shadow appearing at the height of DPH trips. Because of this phenomenon, the entity has become something of an unofficial mascot among DPH users, the embodiment of the sinister and mysterious effects of a drug that most people unwittingly keep in their medicine closets.

The concept of nefarious shadow beings is not particularly unique or novel. From the Nalusa Chito (or ‘big black thing’) of the Choctaw Native Americans to the Tsalmaveth in the Book of Job, the idea of nefarious humanoids lurking in shadows has been a part of the religion, folklore, and mythology of disparate cultures worldwide for thousands of years. What’s more, those suffering from sleep deprivation or sleep paralysis have reported being plagued by shadow people. At least one account from a 2006 research journal reported that doctors in Geneva were able to consistently replicate “the creepy feeling that somebody is close by” when stimulating a particular spot in the left hemisphere of an epileptic patient’s brain – said patient described, again and again, the presence of an unnerving shadow. A 2012 issue of The Primary Care Companion for CNS Disorders also recounts a patient suffering from Lewy Body Dementia who frequently saw “shadow people”.

There are several theories as to what these shadow beings might be. Skeptics may view this as a shared case of pareidolia, the human tendency to seek faces, figures, and familiar meanings in ambiguous stimuli (in this case, shadows). Others believe that the Hatman and his kind are paranormal creatures, akin to ghosts or aliens or demons. Some have hypothesized that shadow figures may travel from another dimension entirely.

Whatever it is, the thing that Benadryl users report seeing straddles the very line between reality and fiction. As a drug-fueled delusion, it is inherently an illusion. At the same time, the Hatman is also not quite a thing of fantasy, as thousands of unrelated individuals have claimed to have really seen him and experienced his foreboding presence. Much of the appeal of recreational Benadryl use lies in it being a conscious choice to willingly enter a state of delirium, to visit the Hatman on one’s own terms, to rip apart the fabric of the universe that our minds work tirelessly to present in logical, digestible terms.

Scary and offputting as the DPH experiences of many may be, there’s a thrill in accessing the forbidden. The promise of an escapist fantasy world – however horrible – is exhilarating in a way that sobriety cannot be. And because of this, a fair number of users become addicted to the petrifying sanctuary delirium offers, despite the ever-present risk each trip holds of permanently finding oneself in the fog of dementia6.

In the weeks following the loss of 13-year-old Jacob Stevens, his family willfully circulated a shocking picture of the youngster tangled in tubes in a hospital bed shortly before his death. As difficult as it is to look at, their hope is that the image might inspire lawmakers to enact age restrictions on over-the-counter medications as well as pressure social media behemoths like TikTok to restrict access to minors.

While the family intentions is coming from a place of wanting to protect other kids, these outcomes seem exceedingly unlikely to happen any time in the near future.

Nice as it would be to believe, this quiet problem is one that a little bit of social media censorship won’t fix. It’s endured long enough among the young, naïve, and invincible in search of a legal high that it can no longer be downplayed as a trend. And so long as people can buy those little pink pills at their local CVS for $7, so long as the dangers are minimized of the drugs we’re conditioned to believe are safe, the Hatman – and all the damage that comes with him – will persist.

This is not to say that the Benadryl Challenge never existed at all. For all we know, social media platforms may be doing their due diligence and immediately deleting content that seems to be sincerely promoting the Benadryl Challenge, as Youtube did during the infamous 2018 Tide Pod Challenge. However, had the Benadryl Challenge ever truly become a viral phenomenon, it almost certainly would have a) garnered more mainstream media coverage and b) found ways to slip past relatively straightforward keyword bans.

Important to note is that diphenhydramine is an active ingredient in Benadryl sold in the United States and Canada – other countries use other formulas, most of which do not cause the same degree of adverse effects.

The medical journal Contemporary Pediatrics reported in 2021 that antihistamine-induced self-harm in patients ages 10-25 has been significantly increasing since 2011.

For those unfamiliar: Slenderman is a piece of modern folklore that originated from a paranormal Photoshop competition held on a SomethingAwful forum in 2009. As his name suggests, he is a tall, thin humanoid that wears a black suit, has no face, and generally spends his time stalking and tormenting hapless victims. There’s no official canonical story surrounding the entity, which inspired thousands to invent their own Slenderman mythologies in the form of fanart and creepypasta. As his popularity increased throughout the early 2010s, he eventually became something of a pop culture icon and caused a brief but memorable moral panic after the urban legend inspired two preteen girls from Wisconsin to commit attempted homicide.

Diphenhydramine has always been dangerous, technically.

As mentioned previously, scientists have linked long-term use of diphenhydramine with increased risks of developing dementia. However, anecdotal accounts suggest that DPH abuse may also cause dementia symptoms to present much earlier in life than would usually be the case. “I feel my mental sanity degrading, I can't think how I used to or see things how I used to, I still see shadows moving even when I'm sober,” writes /u/kivibird1871 on r/DPH. Despite being a subreddit devoted to the recreational use of DPH, it often functions as a space where Redditors warn others of the danger of the drug and comisserate with one another about the tolls DPH has taken on their minds and bodies. Dementia memes are common throughout the forum, evidently used as a means of coping with addiction through humor.

"a fair number of users become addicted to the petrifying sanctuary delirium offers, despite the ever-present risk each trip holds of permanently finding oneself in the fog of dementia."

Does any data support this? To my knowledge deliriants have always been considered among the least addictive drugs, precisely because the subjective experience of one tends toward being so miserable and neutral at best. If they were addictive, one would expect datura addiction would be too considering it grows everywhere like a weed and you might even have some in your own backyard and not realise it, but it's so extremely unattractive to take (even more than dipenhydramine) and unpleasant, hardly anyone tries it even once.

Dipenhydramine has always been seen as a drug stupid teenagers who can't get anything else get high off of once, then never again. Maybe it's new to a lot of people now because of Tiktok and Reddit, but it's been well-known among users of drug forums and psychonauts forever (not sure why you say "self-identified psychonaut" at one point of the article as if there's any other kind; it refers to a certain kind of person with a certain kind of approach to primarily psychedelic drugs, and it's not like you can identify other people as it because that'd require mind reading to know their own intentions or philosophy on using them). It's never taken off in usage since most don't need to try it to realise it's a crappy drug.

Not defending it nor deliriants in general really, they are horrible drugs to the individual taking them. In the past, I've never seen anything but people being discouraged from taking them since it almost universally ends in regret, so a trend like this is really stupid and deserves condemnation. But seeing them called "addictive" is surprising to me, of the people who take deliriants my understanding is most never will again, and it'd take a very strange and exceptional person to actually become addicted to them.

Apologies if any of this unintentionally comes across as critical of your (good) article, I don't mean to be—just surprised by that statement!

DXM is another common OTC drug abused by the same demographic of teens making stupid teen decisions. It's an NMDA antagonist and can be used as a dissociative, it's like ketamine basically. Not as bad as a deliriant, but still stupid to use recreationally. Looks like it has yet to get a Tiktok trend, fortunately, hopefully it stays that way!

This very good and interesting article made me remember an experience from many years ago. One of my son's teenage friends called and said that his little brother, who he was babysitting, had drunk a whole bottle of liquid Benadryl. I did not hesitate but jumped in my car and drove them to the closest ER. They were unable to reach the child's mother, but since it was an emergency, they went ahead and treated him. I don't know what they did since I was not related to him. Afterwards I wondered if it really wasn't that big of a deal. But after reading this I'm glad I reacted as I did then. Thanks!