Imagine, if you will, a cinematic universe in which the act of buying groceries becomes something sacred. Away from the prying eyes of humans, the faces of the frozen-smiled mascots occupying the two-dimensional planes of flimsy plastic and thin cardboard packaging come alive and inhabit a bustling metropolis that exists only in empty supermarket aisles.

Confined to a two-sentence description, this particular universe probably reads as a lazy conduit for blatant advertising, though not necessarily a brainless or moronic idea.

But let’s also imagine that everything that exists within this universe is unforgivably revolting. Despite canonically acting as beloved brand ambassadors, some inhabitants appear to have clawed their way from the deepest gullies of the Uncanny Valley. Others sport bulging unblinking eyes, dermatological disease1, and general anatomical asymmetry. Even individual movements are uncomfortable to witness, existing somewhere between a brittle marionette and a budget Bugs Bunny. What’s more, the repulsiveness of these characters permeates beyond their nightmarish external appearance, as virtually every line of dialogue that exits their poorly rendered, horrifically unsynced lips is either offensive, nonsensical, or some upsetting combination of the two.

Pair all of that with a barely intelligible plot featuring a literal army of 3-inch fascists seeking to exterminate the outliers and “undesirables” of said universe, and you have the 2012 animated abomination that was Foodfight!

A user from an old Somethingawful.com thread had the following to say about the film:

“It is hideous. The script is alternately lazy, asinine, incoherent and inane. The cast is (understandably) totally disinterested. It is racist, sexist and homophobic. Its morals are reprehensible. Its production was a farce, and even the film’s basic premise is toxic. There is nothing. And yet Foodfight! continues to fascinate me with the sheer depths of its incompetence. Every time I see this film I am again stunned by how every element of the story, every single second of film, is so totally devoid of quality.”

For those unfamiliar with Foodfight!, a natural initial inclination might be to question how a piece of media could possibly warrant such a strong yet scathing reaction. Could it really be that bad?

Having watched all 91 minutes of Foodfight! I can confidently confirm that it really is that bad. So much so that I’ve come to understand that SomethingAwful user’s sheer fascination with the film. What goes into making such a fantastically dreadful movie? On a planet populated with billions of people of every imaginable background, how is it possible to make something so universally offensive? Over the past several weeks, I’ve felt compelled to seek out those answers.

The resulting journey has led me down a slippery three-decade-long slope of fad-chasing, media grifting, and market-pandering unlike anything the world of entertainment has ever seen.

Our story begins with a man named Lawrence “Larry” Kasanoff.

The most important thing to understand about Larry Kasanoff is that he’s not some starry-eyed dreamer, driven by fantasies of flashing lights and red carpets. Nor is he a product of the sort of Hollywood nepotism that makes sourcing talent and resources infinitely easier for even the most foolhardy of endeavors. Larry Kasanoff is, at heart, a capitalist. And when he graduated from the prestigious Wharton School of Business sometime in the mid-80s, he recognized that there were vast fortunes to be made in the world of film production.

For context, Larry fortuitously entered the workforce in the thick of an insatiable demand for media. With the VHS having triumphed over Betamax in the videotape format wars of the 1970s, a uniform industry standard was set and VCR sales skyrocketed. This, in turn, lead to a boom in demand for prerecorded media that people could enjoy from the comfort of their homes2. By 1985, there were 15,000 video rental stores3 in the United States alone. But with this boom came a problem –in the early days of home media, there simply weren't enough films made available to fill out rental shelves capable of housing thousands of titles.

As a young man, Kasanoff found a home at Vestron Pictures, a film distributor determined to fill those Blockbuster vacancies by whatever means necessary. “We had to make 80 movies a year for six years,” Larry recounted in a 2023 interview. In addition to buying and acquiring the licensing rights to films created by third-party production companies, Vestron eventually began making movies of its own to reach the behemoth quota. Quality, creativity, and initial expenses were hardly taken into consideration. So long as the film in question wasn’t actively losing money, Vestron would be willing to produce it. And every now and then, one of their low-budget ventures would strike gold. For instance, in order to sell copies of Michael Jackson’s wildly popular song “Thriller” on cassette, Vestron funded a “making of” short film to tack onto the 14-minute music video, in turn creating a feature-length presentation. In conjunction with snagging the distribution rights to a few major successes on VHS (Dirty Dancing and Platoon being two of the most notable)4, Vestron was raking in more money than it knew what to do with.

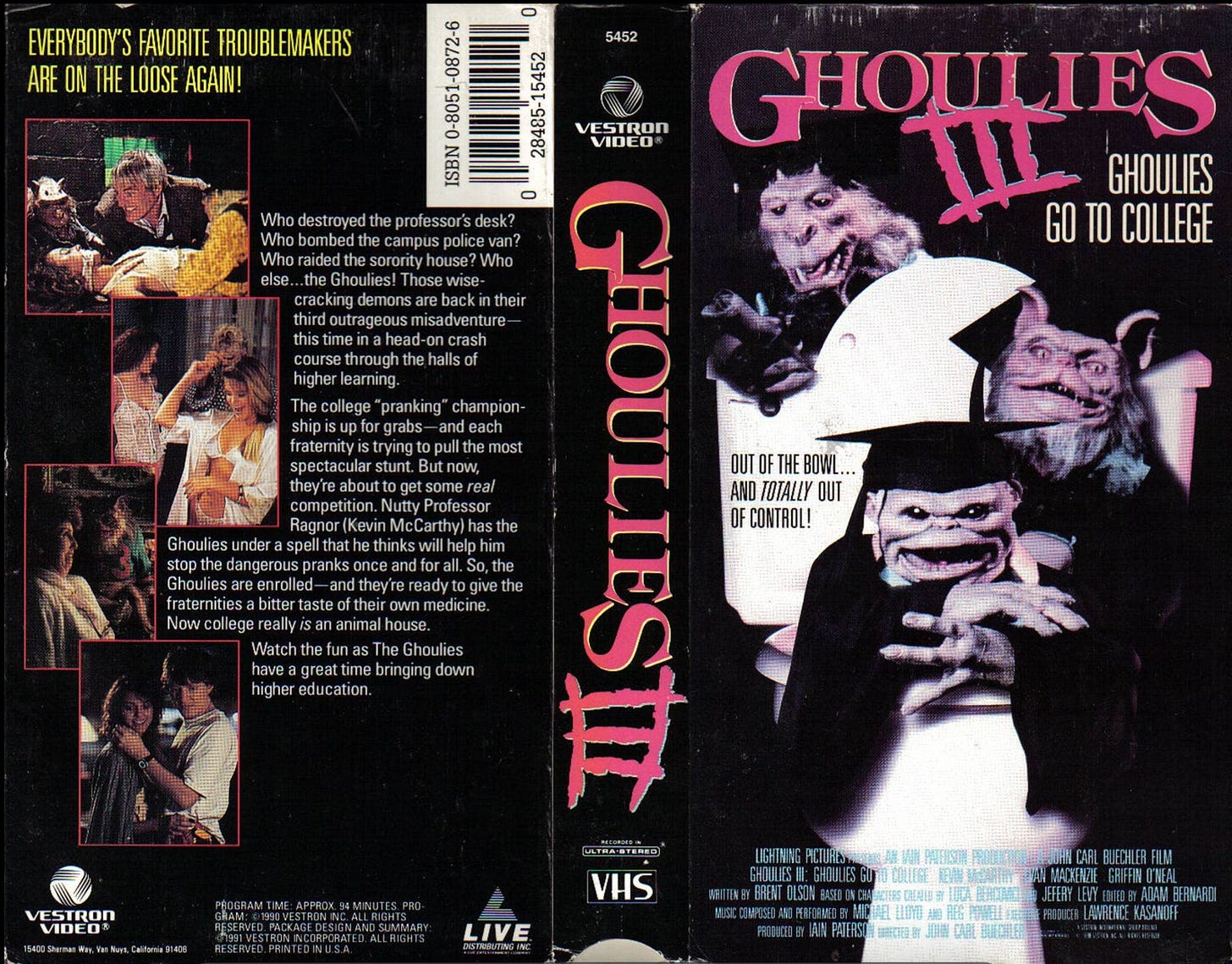

So, Vestron expanded. Kasanoff eventually became the head of Lightning Pictures, a Vestron spin-off that produced films with budgets below $2 million USD. Kasanoff has claimed that Lightning’s business model allowed him to take risks on innovative directors and scripts that pushed the envelope. But, more often than not, Lightning Pictures churned out monstrosities like this:

Despite bringing to life works that at best might be described as shelf filler, Kasanoff became fairly well-connected within the entertainment industry. Vestron crumbled in the early 90s when major movie studios realized the value of maintaining the distribution rights to their creations. Undeterred, Larry went on to found Lightstorm Entertainment with director James Cameron. Kasanoff stepped down from his position by 1993 due to “philosophical differences” with Cameron, but not before Lightstorm released high-grossing hits like Terminator 2 and True Lies that Kasanoff could use to pad his resume (and his wallet).

The sudden influx of clout and cash (thanks in part to the investments of a venture capitalist or two) allowed Kasanoff to found Threshold Entertainment, which bills itself as an intellectual property hub of sorts.

At its inception, two things drove Threshold Entertainment. Its first objective was to acquire and create content that would specifically appeal to boys and men. In a 2000 interview, Kasanoff describes his recipe for success as “Action. Explosions. Cars. Babes.” Threshold’s second objective was to place bets on emerging media outlets largely ignored by mainstream Hollywood.

Some of those bets panned out. In the early 90s, before video games were viewed as viable launch points for multimedia franchises, Kasanoff struck a deal with Midway Games for the “perpetual and exclusive rights” to make films and television series based on Mortal Kombat. Though there have been a few legal snafus regarding the agreement over the years, the deal continues to make Kassanoff and Threshold millions of dollars to this day. Other ventures, such as a martial arts network called Blackbelt TV, seem to be significantly less successful5.

And in the rubble and refuse of a less successful venture, mostly lost to time and software discontinuation, we can find the initial ideas that ultimately launched Foodfight! into existence.

At the start of the new millennium, Larry Kasanoff was one of a handful of Hollywood hotshots who saw potential in the burgeoning field of internet entertainment. Sometime in the late 90s, he used funds from Threshold Entertainment to found TheThreshold.com, aka The Threshold Network. So far as I can tell, the idea was that The Threshold Network would become a nexus for men’s entertainment, capable of offering hours of diversion.

On an archived page titled “Who The Hell Are We?”, thethreshold.com describes itself in the following words:

“We are a destination where the world's most sexy and explosive properties are turned into interactive playgrounds. We want you to come and play, watch, interact, shop, chat, and just have a blast…Remember our Motto: No Crying. No Hugging. No Learning.”

Visitors could buy subscriptions to Men’s Fitness and Maxim alike through Threshold’s magazine marketplace. They could communicate with one another on message boards centered around everything from the upcoming (Kasanoff-produced) Duke Nukem movie6 to stock car racing. The Threshold Network even developed rudimentary games like virtual blackjack.

But the major draw of TheThreshold.com were the “Threshold Babes”. Threshold Entertainment produced a number of shorts in-house featuring beautiful women in various states of undress, all punctuated with a promise that more tantalizing content was soon to come.

Though none of the recurring features were explicitly pornographic, the Threshold Babes were heavily sexualized. A show called “Bikini Masterpiece Theatre” consisted of hotties reading Shakespearean sonnets while donning scanty swimsuits. “Learn the secrets to get babes like this — from the babes themselves…” teases “What Babes Want”, which featured one of the hosts in lingerie and the other with nothing but her own manicured hands to cover her bare chest. “Slumber Party Secrets” prompts users (presumably girls) as young as 13 to share their most intimate secrets, complete with the ability to attach image and video files to authenticate claims. Of course, this included a legal stipulation granting TheThreshold “irrevocable, royalty-free, perpetual license and right to use, display and exploit” submitted content the moment you pressed send.

As foolproof as these titty-centric shorts may sound, Kasanoff quickly ran into a big problem – sharing video clips on the internet in the late 90s was a colossal pain in the ass. The infrastructure to transmit large video files was simply not yet in place. While you could host videos on a website, slow internet speeds and limited bandwidth made them impossible to watch without significant buffering and interruption. If Kasanoff was going to have the Threshold Network take over the internet, he was going to need to look into media that wasn’t quite so clunky.

And almost as quickly as he realized the problem, he found a solution in Flash animation.

Kasanoff – and many other entrepreneurs pioneering the uncharted waters of online entertainment – found that animation was able to bypass many of the technical issues that plagued streaming video. Flash animations had much smaller file sizes, which would cut down buffer time and allow for higher-definition imagery. But what was likely even more appealing to Kasanoff was the fact that Flash animation could be produced on a shoestring budget in comparison to traditional flesh-and-blood live-action content.

So, by the start of 2000, Kasanoff had 18 web-exclusive series in the works. The babes weren’t deserted entirely. However, it appears that Threshold resources pivoted toward creating comedy shorts that hinged on fart jokes, racial stereotypes, and other forms of crude humor to accrue laughs7.

Probably not coincidentally, around the time Threshold Entertainment started experimenting with webtoons, Kasanoff (or someone Kasanoff adjacent) had a truly dastardly thought: “What might happen if Threshold really leaned into animation?”

In 2000, Pixar had firmly established itself as the reigning monarch of 3D animation. But they lacked a formidable rival. Why couldn’t Threshold become that adversary? After all, even features utilizing state-of-the-art8 computer animation could be made for far less than the average Hollywood film9.

And just like that, Foodfight! was born.

The plot that Larry and co-producer Joshua Wexler cobbled together was simple enough. Our heroes, Dex Dogtective (who is a dog detective) and his quirky sidekick Daredevil Dan (a chocolate (i.e. black-coded) squirrel that I assume was intended to be the Donkey to Dex’s Shrek) inhabit the aisles of a grocery store, which turns into a bustling metropolis after hours. But when evil Brand X (clearly meant to symbolize store brand and generic products) comes to town and Dex’s hot humanoid girlfriend becomes a damsel in distress, Dogtective and his friends must work together to restore peace and order to the supermarket.

But that was just the beginning. Foodfight! would be the Magna Carta of all product placements. Dozens of brand mascots would make cameos throughout the film, all fighting the noble fight (against products equivalent in quality but less expensive). Each mascot – or “icon”, as they’re referred to in the film – would add their own unique touches to the extended Foodfight! universe.

Picture it. Chester Cheeto, the Cheeto-eating wildcat whose eyes are always hidden behind dark sunglasses, would ride a gnarly motorcycle through the city streets to cement how Supremely Cool he is. The Sun-Maid California Raisins would remind viewers of their famous 80s ad campaign with an epic performance of “I Heard It Through the Grapevine”. A strong, stoic, and silent Mr. Clean would eviscerate the mess a title like Foodfight! promises. The idea was that this film would do for these products what Toy Story did for Mr. Potato Head.

In Threshold’s mind, this film couldn’t go wrong. Foodfight! would be a guaranteed win. Without a doubt, it would be historic production.

And it would be historic – just not in the way the minds behind the film had imagined.

Larry’s enthusiasm for his own brilliant idea made securing the funds for Foodfight! pretty easy. Many claim that Kasanoff had a $65 million USD budget, though a 2004 New York Times article suggests that even more money than that was dumped into the project. About a third of the money came from a Korean investment consortium. The rest came from licensing the distribution rights abroad (and then making loans against those pre-sales).

To be perfectly clear, $65-75 million USD was a hefty budget for an animated film in the early 2000s. In 1995, Toy Story was produced at less than half the cost. Chicken Run (2000, $42 million USD) and Ice Age (2002, $59 million USD) were cheaper, too. Even Shrek (2001), a movie that had to be entirely reworked because its main voice actor died mid-production, was only $60 million USD.

Knowing that other studios working were making much better for significantly less begs the question of what, exactly, Foodfight!’s bloated budget was spent on.

Almost certainly, a fair amount of funds went into securing a superstar cast. Or, at the very least, what Kasanoff perceived as a superstar cast. Actor Charlie Sheen was selected to voice protagonist Dex Dogtective – an interesting choice to play the straight-laced hero of a children's movie, considering the actor’s extensive history of bad behavior10. Hillary Duff snagged the role of Dex's love interest Sunshine Goodness, a truly horrifying catgirl and mascot for a fictional brand of raisins11. Duff was at the height of her popularity at the time of casting, which apparently offset the fact that she was either 14 or 15 years old (not to mention 22 years younger than Sheen). Wayne Brady, best known as a fixture of the popular comedy program Who's Line Is It Anyway, would play quirky sidekick Daredevil Dan, and Eva Longoria (at the time primarily a soap opera star) earned the role of femme fatale Lady X.

No matter how you slice it, the main cast was a strange configuration of performers that really didn’t make sense being put together. There isn’t an iota of chemistry between any two characters. But perhaps in the minds of Threshold Entertainment producers, this was an issue that could be fixed in post-processing. After all, name recognition alone would bring in a fair number of viewers.

Another significant chunk of the funds went toward negotiating usage rights with brand managers. While one might assume that businesses would embrace the idea of free advertising – maybe even pay for the opportunity to have their beloved mascots represented – this was not the case. Instead, it took about two years of paying licensing fees and hammering out the terms of what Kasanoff could and could not do with characters like Count Chocula. While getting permission for over 80 food-industry mascots was likely tedious and expensive, more mascots meant more promotional crossover opportunities. And a predicted $100 million USD merchandising campaign was how Kasanoff planned on turning a profit.

If the plan went smoothly, everything from bottles of Coke to bags of peanut M&Ms would promote Dex Dogtective and Daredevil Dan, compelling viewers to visit their nearest cinema as quickly as possible. Hell, manufacturers like General Mills would likely be begging Kasanoff for the opportunity to make a Dex-themed sugary cereal that ravenous kids would clamor for. From there, they could start selling toys and apparel for fans of all ages. Foodfight! spin-off webisodes would further flesh out the universe. Foodfight on Ice! tickets would practically sell themselves.

So once Threshold Entertainment got the green light, staff got to work breathing life into the concept. Instead of contracting an experienced animation studio to bring Foodfight! to life, Threshold initially insisted on maintaining complete control over all aspects of the film. After all, how could Threshold become the next Pixar if they didn’t even have their own animators?

This was probably the first sign that Foodfight! might not become the slam-dunk hit it was hyped up to be. Animators who worked on the film have since claimed that Kasanoff lacked knowledge concerning the basic fundamentals of animation. Infamously, he’d peer at work-in-progress over artists’ shoulders and request they make animations “30% better” without any further elaboration on what that actually meant.

A layout artist named Kenneth Wiatrak recalled the following about his time spent developing the film:

“[Kasanoff’s"] approach, because he had gotten the money for it, and no one could say no to him, was very idiosyncratic…You didn’t know from day to day what would occur. Would there be a review? Would he suddenly want to change the whole thing?”

Nevertheless, an early trailer reveals that at one point the animation was acceptable for its time. It’s definitely less sophisticated than a Pixar film such as Finding Nemo (2003), but it’s certainly not far off from something like Jimmy Neutron: Boy Genius (2001).

But in the winter of 2002, about 6 months into production, an unprecedented event still shrouded in mystery would cement Foodfight!’s spot in infamy.

While Threshold Entertainment’s staff celebrated Christmas holidays with their families, what Kasanoff described as an “incredibly complex crime” took place that would prove to be catastrophic. The story goes that someway, somehow, an unidentified burglar breached Threshold’s Santa Monica studio, made their way into a “room within a room within a room”, and stole the hard drives on which the movie was stored. Presumably because of Kasanoff’s refusal to outsource any of the work, all of the files were stored in a single location12, meaning that aside from a few reference images, the entire production was lost.

In the years since the incident, Kasanoff has claimed that the theft was an act of “industrial espionage”. That is to say, rival animation studios conspired to destroy Foodfight! before it became a threat. The United States Secret Service investigated the large-scale intellectual property theft, but the crime remains unsolved. No arrests were made, and no trace of the original Foodfight! film has ever surfaced. Some amateur detectives online have theorized that Kasanoff (or some other Threshold employee) either accidentally or purposely13 destroyed the film themselves. Though there’s no evidence suggesting that this is what happened, the theory seems significantly more likely than John Lasseter or some other animation bigwig masterminding a criminal heist to destroy Threshold.

Regardless of what happened, the work was gone and the initial 2003 release date was pushed back. After a year spent reconceptualizing the project, Threshold resumed production in 2004.

But the fresh start brought with it drastic changes. Initially, Foodfight! was set to utilize a “squash and stretch” animation style, with hyper-exaggerated movements and expressions comparable to what you might see in a Looney Tunes short. It’s often what makes stylized animations feel alive and dynamic, and presumably the first version of Foodfight! would have had artists working with traditional frame-by-frame animation. After the theft, however, Kasanoff made the decision to abandon more traditional techniques in favor of utilizing motion-capture technology. Foodfight! 2.0 would record the movements of live actors and would thus be directed more like a live-action movie – complete with retakes and improvisation. Once the necessary data was recorded, it would be uploaded and applied to animated models.

Theoretically, the switch to mo-cap should have streamlined filmmaking by speeding up the animation process and reducing overall labor costs. But in practice, this was not what happened.

Evidently, earlier setbacks had eaten up much of Foodfight!’s initial funding. But the movie still boasted a star-studded cast and dozens of brand tie-ins, making it possible for Threshold and Kasanoff to procure an additional $20 million USD to bring the new-and-improved movie to life. With funds in hand, Kasanoff struck a distribution deal with Lionsgate and promised a Fall 2006 release.

But 2006 came and went without a finished product. A second release date was set for 2007, but Threshold once again failed to deliver a completed film in time. Unamused by the missed deadline, Lionsgate pulled out of the project. Over half of the originally planned brands backed out, in all probability were no longer willing to have their famous faces attached to such a disaster. Time passed without results. Kasanoff, either frustrated or bored with the project, seemed to move on to bigger and better things (which, in this case, primarily seems to have consisted of LEGO-affiliated content14).

The few that became invested in actually seeing the bizarre little bit of lost media started losing hope that they’d ever have the opportunity to lay eyes on Foodfight! That is, until September 2011, when an unexpected, unassuming classified ad appeared toward the back of an issue of The Hollywood Reporter:

In its stagnation, Foodfight! had become negative equity – that is, the debts incurred during the making of the film far outweighed what the film would concievably be able to gross in theaters. Kasanoff opted to default on a secured promissory note, which for those unfamiliar, is a legal obligation to repay a loan in which a payee’s property or assets acts as collateral. Should the debtor fail to follow the terms of the promissory note, the lender may then seize ownership of the asset or property that “secured” the initial loan.

Apparently, Foodfight! itself served as the collateral at stake. Frustrated by the years of production hell that yielded no return on their investment, Foodfight!’s second round of funders enacted a clause that allowed the (now defunct) Fireman’s Fund Insurance Agency to obtain the intellectual property rights and “complete the film as quickly and cheaply as possible”.

So, the insurance company did just that and proceeded to sell the end result to the highest bidder in a public auction. According to an article from Animation Magazine, British publisher Boulevard Entertainment acquired the rights15. Against the odds, in June 2012 – nearly a decade after its intended release – Foodfight! finally enjoyed a limited release in UK theaters. At long last, the morbidly curious could see for themselves whether the film was as terrifically bad as sparse forums on the topic suggested it might be.

And once they did, it immediately became clear that “bad” doesn’t even begin to describe the atrocity that had been unleashed.

The first thing that becomes blatantly obvious when viewing Foodfight! – and you can view it, because the entire film is free to watch on Youtube – is that nothing makes sense. I don’t mean this in a cartoon there-are-no-laws-of-physics sort of way. I mean that for even the most open-minded viewers, understanding the basic environment that Dex and crew inhabit is genuinely confusing.

It’s firmly established in the movie trailer that Marketopolis Market becomes a lively city away from the prying eyes of customers. But when the shopkeeper closes up shop, the inside of the establishment no longer even vaguely resembles the aisles of a grocery store. The city that these brand icons inhabit is paved with cobblestone and has a river flowing through it. One of the film’s opening scenes features Dex wining and dining Sunshine Goodness in a meadow that inexplicably exists within the supermarket. Not in the produce section, where our Dogtective might have logically picnicked on a bed of leafy greens that could convey the feeling of a grassy knoll while fitting inside a grocery store setting. No. The scene is in a meadow, complete with grass, trees, sky, and wildflowers.

If this comes off as nitpicking, don’t worry. The logical fallacies of this film are far from its greatest sin. In a truly impressive feat, Foodfight! 2.0 actually looks significantly worse than its pre-theft predecessor.

The decision to switch from traditional frame-by-frame animation to mo-cap yielded extremely unsettling results. As it turns out, the movements of a being bound by the constraints of reality come off as stiff and disconcerting when applied to a realm where cartoon violence and exaggerated actions are within the realm of possibility. Even mo-cap-heavy animations that used the best actors and most nuanced technology available, such as 2004’s Polar Express, were criticized for dipping into uncanny valley territory.

And, as it probably goes without saying, neither the talent nor the tech utilized for Foodfight! was likely to be the best money could buy.

To make matters worse, according to the 2013 New York Times article cited earlier, the software used to sync filmed voice actor performances to animation faced some serious limitations. In order to capture any movement at all, Charlie Sheen and co-stars had to stare straight ahead and stay as still possible as they read their lines. This resulted in virtually expressionless faces complete with vacant, unblinking eyes.

Considering Foodfight!’s origins can be traced back to the Threshold Babes, the sexual innuendo that permeates this film really shouldn’t come as a surprise. Nevertheless, both the frequency and the sheer explicitness of said innuendo is shocking for a movie presumably geared toward children. Foodfight! goes beyond the cheeky adult-oriented jokes that cartoons often slip in to get a chuckle out of parents. Instead, we the audience are subjected to Daredevil Dan the chocolate squirrel catcalling humanoid women, heavily implying he’d love to cum all over her. We get not one, but TWO dance sequences in which Lady X actively tries to seduce an anthropomorphic dog with “her secret ingredient”. One of these sequences features her in a fetishized schoolgirl outfit for no discernable reason. Cheasel T. Weasel, voiced by Larry Kasanoff himself, offers to sell a downtrodden Dex what appears to be a blow-up sex doll as a companion for “those lonely bachelor nights”. On the subject of Cheasel, the weasel is shaped like a literal dick and balls, which is used for comic effect when he slithers his inexplicably long neck between Dex’s doggy thighs.

It’s impossible to pinpoint a single worst aspect of Foodfight!, but perhaps the most baffling element of all is the wildly anti-semitic plot. To say that Brand X is Nazi-coded and the crimes that they commit are reminiscent of the Holocaust truly doesn’t do the film justice. Short of giving Lady X a Hitler-esque mustache, the allusions are about as explicit as possible. The primary conflict driving the story occurs when Brand X organizes an army that starts physically torturing and murdering brand icons – who are unfortunately nicknamed “ikes” – in order to free up space for their product in the aisles of Marketopolis. As the soldiers march through the streets with salutes that resemble a modified Sieg Heil, it’s nearly impossible to avoid drawing comparisons to long-dead German troops parading through Europe in full regalia.

At one point, Lady X and her cronies try to eliminate Dex and Dan by trapping them in a suspiciously oven-like drying machine that’s so hot it produces flames. X HQ is literally plastered with Reichsadler Imperial Eagles. Before General X is crushed to death by a can of Dinty Moore beef stew, he pleads that he was “just following orders”, in reference to the Nuremberg Defense that actual Nazis plead following World War II. In the final moments of the movie, we even discover that Dex is Jewish – from a (fictional) anti-histamine mascot that sports Woody Allen’s thick-rimmed eyeglasses, a heavy Brooklyn accent, and an impossibly gigantic nose.

I could easily continue ragging on this film. But after a certain point, dissecting a needlessly racist caricature like Kung Tofu or pointing out the particular moment in which an astoundingly grotesque frog defecates all over an unphased Mr. Clean feels a bit like beating a dead horse.

The extended Casablance-inspired La Marseillaise battle cry, the near constant Nazi-adjacent imagery, the inclusion of Mrs. Butterworth and the Vlasic Pickle stork – the entire production is a rehash of existing ideas forced together into something barely coherent. Threshold always prioritized sales above art itself. As a result, behind the copious layers of branding, the famous names, the brightly colored animations and attempts at potty humor, Foodfight! was empty. Souless. Void of meaning aside from pure consumption. And for that reason, from conception to the bowels of stray bargain movie bins, it was always doomed.

Ultimately, the muti-million dollar disaster grossed about £16,400 GBP in the box office. Slowly, other countries gained access to the long awaited feature. Viva Entertainment LLC eventually obtained US distribution rights and would wait until May 2013 to quietly sell the movie on DVD in Walmarts nationwide. Profits were so low in the movie’s country of origin that no one even bothered to record and publicize the numbers. Threshold Entertainment, still active to date, makes no mention of the film on its official website. Though its never been explicitly expressed, it’s clear that those involved with Foodfight! feel that its best forgotten.

But in what’s seemingly an act of defiance against its own creators, the remnants of Foodfight! continue to linger well past its expiration date. Every so often, a Daredevil Dan or Cheasel T. Weasel plush will still mysteriously appear as a prize at the bottom of bowling alley arcade games or strapped to the frames of traveling carnival booths, like roving cryptids. Particularly ridiculous sequences, removed from their original context, are sometimes utilized as reaction GIFs. My best friend, a teacher at a Massachusetts high school, claims to have witnessed giggling students clamoring around an iPhone streaming the film during an otherwise quiet study hall period.

Having not been there, I obviously can’t confirm the validity of that anecdote. But as vile and unwatchable as the movie is, in a weird contradictory way I like to think that a new generation has independently discovered the absurdity of this strange, uniquely detestable farce of a film.

Because, for better or worse, there’s nothing quite like Foodfight!

Okay, I’ll admit that none of the characters are supposed to be diseased canonically, but take a good hard look at these two and you’ll see what I mean.

(Not unlike the content boom that we're now experiencing with the advent of subscription streaming services, or the clamor for original programming that stemmed from the introduction of cable television)

This is especially impressive considering the first video rental store was conceived in 1975. Understanding the dramatic jump from 0 such facilities to 15,000+ in a ten-year span really puts into perspective how sudden and formidable the demand for new media truly was in the 80s and 90s. It also explains how a company like Vestron (that is, solely concerned with creating as much content possible) was able to thrive.

Again, though Vestron produced a handful of low-budget B-films, Vestron was primarily in the business of distributing films produced by other companies. Although Kasanoff often takes credit for the successes of films like Platoon and Dirty Dancing, it’s worth noting that Kasanoff was not involved in the creative process of either film, both of which were produced by companies unrelated to Vestron.

Blackbelt TV is available to stream on Roku. I don’t have Roku TV, and I’m not buying a Roku for the purpose of this article. But if you own Roku TV, please let me know if it’s as bad as the sole written review I could find suggests that it is.

Spoiler: The Kasanoff-produced Duke Nukem movie never made it past pre-production planning phases.

Unfortunately (or maybe fortunately?) the discontinuation of Adobe Flash combined with the site itself only being viewable via internet archives has made viewing these shorts difficult, if not virtually impossible.

(At least, for the time.)

According to the New York Times, the Motion Picture Association of America reported that the average Hollywood movie had a budget of $60 million in 1997.

Though the production of Foodfight! began about a decade before Sheen’s highly publicized 2011 meltdown, the actor was still embroiled in controversy throughout the 90s. In 1990, he may or may not have accidentally shot his fiancee Kelly Preston in the arm (naturally, they broke up soon after). In 1995 he was forced to testify (in exchange for legal immunity) that he had spent tens of thousands of dollars on prostitutes over the years. In 1998, he nearly died after a cocaine binge led to a stroke.

This is funny because raisins are poisonous to dogs. They are also poisonous to cats, although it’s not really clear whether Sunshine Goodness is canonically a woman, a cat, or a chimera of some sort.

While this is kind of hard to believe, if ever there was a movie to not have backups stored somewhere, it would probably be Foodfight!

Conveniently, the film was at least partially insured (though it’s unclear just how much the insurance paid out or where those funds were allocated). Some skeptics believe that the work may have been destroyed to allow production to go in a different artistic direction with the project.

It should be noted that the LEGO movies and series that Threshold Entertainment produced, which were primarily made-for-tv or direct-to-video specials, ARE NOT affiliated with the popular The LEGO Movie franchise.

This may not be an entirely accurate statement. The DVD release attributes copyright to the Fireman's Insurance Fund. Boulevard did, however, handle distribution in the UK.

this is a wonderful review of how Food Fight animated nazi tripe as guard dog and crew save sacred foodtown, that stacks up tropes, till senseless, and plugs every label, I havent watched it,,,,,, I will take your word for it.