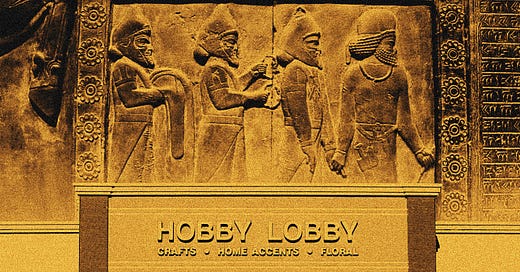

The Great Hobby Lobby Artifact Heist

How an American Evangelical arts and crafts empire managed to loot antiquities en masse from a long-lost Mesopotamian city-state. (Pt. 1 of 2)

Around four thousand years ago, in a metropolis called Irisagrig situated between the Euphrates and Tigris rivers, a people thrived. Even in the eyes of their most direct modern ancestors, these people would have seemed almost alien – they spoke in languages that have long since died out, wore strange woolen clothes out of place in the arid desert that’s since usurped their former homes. But they were unmistakably people, and they did all of the things that people do to make day-to-day life something more than a frantic struggle for survival. These people developed numeral systems and learned to work with metal and clay. They enslaved each other, and, in quiet moments, dreamed about gods and the heavens.

No one is entirely certain where Irisagrig once stood because it was abandoned and fell into disrepair many centuries ago. This isn’t particularly unusual. Many ancient cities have met similar fates. In some cases, new people built new cities right atop the ruins of old ones. Irisagrig is among the countless that simply faded away. Over hundreds of years, vacant structures were eroded by the wind and forgotten entirely, reduced to little more than innocuous earthen mounds.

Nevertheless, we know about Irisagrig because the people who lived there carefully carved cuneiform characters that told of their experiences. While mud-brick structures crumbled, these words survived. Surely, some scribes must have realized that their records borne of chisel and stone would long outlive them.

But even the most imaginative of men could not have fathomed just how far some of their words would one day travel.

I don’t mean this figuratively, in the way intangible ideas transmit from person to person. Rather, I mean that in 2010, after multiple millennia untouched, tens of thousands of Irsagrig cuneiform texts were physically smuggled into Oklahoma City. Specifically, to the headquarters of an arts and crafts chain called Hobby Lobby.

If you live in the continental United States, you’ve almost certainly seen a Hobby Lobby before. There are over 1000 locations, and more often than not, they’re hulking establishments. Their size is part of their business model. Just as the progeny of Irisagrig built impressive city-states atop the derelict structures neighboring forefathers left empty, Hobby Lobby locations tend to pop up in the abandoned storefronts of businesses past. Land once occupied by a dying, hulking giant like Circuit City or KMart or Bed Bath & Beyond is often available for rent at a steep discount from owners eager to collect on space that would otherwise collect dust and attract vandals.

No matter how sprawling the locale in question, Hobby Lobby manages to find ways to pack aisles with everything from macrame to silk flowers. Through the sale of countless buttons and sequins and knitting needle sets in the aisles of these behemoths, the Green family – the sole owners of the Hobby Lobby empire – have accrued the sort of vast fortune necessary to purchase priceless antiquities wholesale.

This begs an obvious question. The cuneiform texts of an ancient Mesopotamian people should, in theory, hold little interest to an arts and crafts vendor based in the midwestern United States. So why, exactly, would Hobby Lobby shell out millions of dollars to get their hands on stone tablets crafted so many years ago?

To grasp the rationale, it’s necessary to understand the values the Green family holds closest to heart.

The fifth of six children fathered by Rev. Walter Green, God has always been at the forefront of Hobby Lobby patriarch David Green’s life. As a child, his family lived in relative poverty while serving small congregations across the country. David was shielded from much of what the secular world had to offer; he was discouraged from playing sports, watching movies, listening to music on the radio, or participating in anything the Reverand Green deemed “worldly activities”. Finances and a fervent need to spread the word of God kept the Greens constantly moving, preventing David from establishing longstanding friendships with other children. As David’s siblings grew up one by one, each either married a pastor or started their own ministry.

But David’s calling was different – instead of church pews, he found God working in retail. Specifically, a five-and-dime store called McClellan’s in Altus, Oklahoma. By the time Green graduated from high school, he clocked in 60-hour work weeks. His persistence landed him an assistant manager role with another local five-and-dime chain, TG&Y, when McClellan’s shuttered its doors. Throughout the 1960s, TG&Y rapidly expanded, and David climbed the corporate ladder.

TG&Y wasn’t a perfect operation by any means, but it was something akin to Walmart – the sort of place where you could get just about anything you needed. By the 1970s, Green was a district manager with an intimate understanding of the business and its inventory. Hoping to make some extra cash supplying TG&Y with a new product, Green and a fellow TG&Y overseer took out a $600 loan and began crafting “miniature frames”. However, their haphazard prototypes instead caught the attention of mom-and-pop craft stores throughout the Midwest.

The operation expanded, leading Green to set up a small factory. There, he staffed “cerebral palsy patients” to chop, glue, and bag frames for $.10 per piece. Between the high demand and likely paying workers a subminimum wage1, profits soared and inventory was expanded to include beads and other basic craft supplies. By the mid-seventies, the business was successful enough to buy out a 50,000-square-foot complex that would eventually become the first Hobby Lobby.

All the while, Green was gradually starting to realize his purpose. He adopted a Christian capitalist worldview centered around personal wealth as a precision tool to carry out God’s will. His calling was one of stewardship, in which financial assets could be used to better the lives of others in any way he saw fit, free of middlemen with misaligned convictions. Rapid growth quickly became the primary objective, because, in the minds of the Greens, total profits directly correlated with opportunities to serve the Lord.

Expanding Hobby Lobby proved easy because Hobby Lobby was unlike anything anyone had ever seen. At the time, there wasn’t a clear-cut idea of what a catch-all hobby store should be. While independent hobby stores certainly existed, most were limited to small locales with a finite number of specialized supplies2. Some familiar US arts and crafts retail chains were establishing roots, but on much smaller scales. For instance, Michael’s – Hobby Lobby’s primary competitor – was largely sequestered to a handful of stores in Texas until 1984. Jo-Ann’s, currently on the precipice of total annihilation, was a fabric supplier that didn’t introduce craft supplies to its inventory until the 1990s. Now defunct A.C. Moore wouldn’t open the doors to its first store until 1985. Blick predated Hobby Lobby, but historically conducted the majority of its business via mail order, advertising professional-grade wares in glossy catalogs rather than on display in brick-and-mortar locations.

Hobby Lobby, in contrast, was an institution built for the crafty proletariat. Massive outlets were filled with a wide range of supplies sold at reasonable prices. Customers could discover new mediums to explore while browsing the aisles, touch walls packed with textiles, and examine in depth the physical qualities of pencils, papers, and paints. Any artist, regardless of skill or experience, can attest to the value that lies in this sort of tactile interaction with materials. As a result, Hobby Lobby thrived, spreading across the country like wildfire.

The term “arts and crafts” conjures humble images of primary school children gluing together popsicle sticks, of grannies weaving needles through embroidery hoops. For many, it’s a label applied to works too provincial, too amateur to grace the walls of prestigious galleries. In reality, the global arts and crafts sector is a near recession-proof, evergreen industry roughly valued somewhere between $40 and $50 billion USD. Fifty years in, Hobby Lobby plays an almost unfathomably massive role within this ecosystem. Despite recessions, pandemics, and competition in the form of e-commerce, Hobby Lobby's revenue has steadily increased over the years, with Forbes reporting a whopping $8 billion USD in revenue in 2024.

While not quite a monopoly, Hobby Lobby is perhaps the industry’s most influential retailer, with a tight hold on a substantial portion of the total global market share. But unlike other major players in the arts and crafts industry, Hobby Lobby is a private corporation owned in full by David Green and his family. It’s all a part of Green’s initial calling toward prosperity theology; without shareholders to appease, nothing stands in the way of redirecting Hobby Lobby profits into missionary endeavors. The Green family has consequently accrued a multi-billion dollar fortune and become one of the largest donors to Evangelical causes in America.

While the total amount the Greens have made in charitable contributions has been kept private3, former Oral Roberts University president Dr. Mark Rutland may have worded it best when he described the family as “kingdom givers”. In 2008, the Greens “rescued” the university with a $70 million “gift” following a damning lawsuit documenting dozens of instances of misconduct. They provided Liberty University with a former manufacturing plant worth $10.5 million, which would later become the site of the Thomas Road Baptist megachurch. For another $16.5 million, the Greens purchased an entire campus for Northpoint Bible College and Seminary4 in Haverhill, MA. Missouri’s Evangel University received not one, but two separate $10 million donations from the Green family.

This is to say nothing of evangelizing initiatives largely or entirely funded by Hobby Lobby. The Green family has devoted millions of dollars toward projects focused on “systemically and strategically” spreading the gospel worldwide. These strategies range from developing apps linked to comprehensive Christian content libraries5 to missionary work and church planting in isolated communities6. A substantial (but undisclosed) amount of money has been donated to the Servant Foundation, best known for launching the slick “apolitical” “He Gets Us” ad campaign, shoehorned into Super Bowl commercials and NASCAR decals alike in an attempt to reach young adults and skeptics78. David’s eldest son, Mart, has financed several Christian media production companies9 throughout the past two decades, served as the leader of an organization aimed at “eradicating bible poverty”, and founded a chain of Christian bookstores.

The list goes on further, but the point is this: American Evangelical academia, charities, politics, and media are integrally tied to Hobby Lobby and its founding family. A fortune built on the sales of sewing notions and glitter has paid for many of the country’s most influential megachurches and scriptures delivered to the most remote corners of the world. A careful calculation of potential proselytized souls drives every financial decision.

And in 2010, the Greens took on their biggest endeavor yet: the creation of a 430,000-square-foot, highly interactive museum solely devoted to the entirety of biblical history.

The idea first came about through Donald “Johnny” Shipman, an evangelical Christian entrepreneur who dabbled in everything from oil drilling to the sale of wholesale jewelry. His true passion, however, lay within the world of biblical artifacts and manuscripts. Sometime in the early 2000s, Shipman felt a “distinct calling from God” to “found a Bible museum to impact the world with the knowledge of God’s Word”. It would be no less than 10 football fields in size, located in the heart of Texas, where everything is bigger. It would be immersive, an experience that would join new media and technology with the ancient, sacred words of disciples past. It would galvanize the souls of those who walked through its halls and bring God to even the most skeptical of visitors.

Unfortunately, Shipman had neither the expertise nor the funds to pull off such an endeavor. Unwilling to let his lofty dreams become stifled by his earthly limitations, however, the business magnate set to work finding helping hands.

He soon found aid in the form of Scott Carroll, an evangelical multidisciplinary ancient artifact expert known for using archeological evidence in his teachings to support the veracity of biblical events and spark interest in the origins of Christianity. To some, his methods were highly questionable – according to papyrologist Roberta Mazza, Carroll frequently allowed audiences to freely touch and handle Jewish Torah scrolls, cuneiform tablets, and other such rarities. Journalists Candida Moss and Joel Baden reported in the 2017 book Bible Nation that Carroll went so far as to encourage undergraduate students to taste artifacts. Despite these eccentricities, his questionable methods seemed to be legitimately effective at hooking curious audiences and budding scholars alike. Furthermore, Carroll played an integral role in assembling and maintaining the late Robert Van Kampen’s collection of rare Bibles and manuscripts, among the largest in the world of its kind10. His enthusiasm, experience, and strong Evangelical faith made him a perfect candidate to materialize the institution of Shipman’s dreams.

Left with the predicament of securing the funds necessary to launch such an ambitious endeavor, Shipman naturally turned to the Green family.

Shipman first became acquainted with the family while aiding Mart Green in the production of a 2005 movie titled End of the Spear. From that moment on, he frequently sojourned to Hobby Lobby’s Oklahoma City campus in hopes of convincing the Greens to bankroll (and, subsequently, donate priceless artifacts) to a proposed National Bible Museum in Dallas.

Initially, Shipman grated on the family. The Greens allegedly had little interest in his pet project, conceptually speaking. However, years of pestering ultimately persuaded David Green and his sons that the serious potential to profit was hidden within the world of stuffy artifacts.

Long before Shipman came around, the Greens devised a means of garnering huge profits off the “charitable” donations of real estate. They’d buy undesirable plots on the cheap, sometimes invest a bit in fixing them up, and then hand them off free of charge to other evangelical organizations to do with the land whatever they wished. The Green campus donations to Liberty University and Northpoint Bible College serve as two highly publicized examples of this outwardly generous practice. Less evident are the sizable tax breaks that result from such charitable contributions. These tax write-offs are calculated using the highest appraisals possible, which is not necessarily indicative of the actual sum of money paid out by the Green family for the land. Counterintuitive as it may seem, this practice frequently allows the Greens to save far more money than they spend via hefty deductions. In their eyes, it’s a means of optimizing potential evangelical ministry rather than fraud-adjacent praxis; “worthy” organizations are given resources, and the donation pool for future causes grows larger.

The same principles are easily applicable to antiquities. The value of such items lies not in the physical materials themselves, nor the hours of labor expended thousands of years past, but in a nebulous, immeasurable, highly subjective perception of cultural and historical worth. This leaves a substantial amount of wiggle room for appraisers that’s difficult for discerning parties to argue. How does one evaluate (or argue against) the worth assigned to the echoes of civilization’s past?

And so, the Green Collection was born in 2009. Scott Carroll’s expertise in the field earned him the title of director, and he immediately set to work scouting out antiquities of interest. Shipman’s role revolved around negotiating purchase terms with dealers. The Green family served as benefactors, authorizing the sales of items that would yield a worthwhile ROI11. Artifacts would then be shipped to Oklahoma City and stored away in a Hobby Lobby-funded archival facility12 while plans for the hypothetical museum were further solidified.

Under the supervision of this small team, the Green Collection expanded at a staggering rate. Over the course of 40 months, Hobby Lobby acquired over 40,000 artifacts in an unprecedented buying blitz.

The majority of institutions in art and academia are careful in their curatorial processes, handpicking specific items from private collectors and auction houses. Hobby Lobby, a business intent on evangelizing at whatever cost necessary, adopted a radically different approach to acquisition. Always in search of a bargain, the Greens bought their antiquities in bulk, clearing out entire private collections. Sometimes, if the price was right and the goods were promising, they’d blindly purchase hundreds of yet-to-be-studied relics in a single transaction.

Most troubling was the indeterminate provenance of some (but not all) of the objects that fell into Hobby Lobby's hands.

Provenance (the detailed chronology of an object’s ownership) provides important context in determining exactly when and where an object came from. It helps differentiate convincing counterfeits from authentic antiquities. But, perhaps most importantly, proof of provenance is important in ensuring that ownership of an artifact is obtained through legal and ethical means. For centuries, the stuff of museum halls has been plundered as spoils of war. Each loss is something irreplaceable, a fragment of a nation’s cultural heritage eviscerated. As the vestiges of forefathers crumble and the backstories of such objects are lost between hands, thieves with no regard for the memories of dead men profit. To require provenance deters such looting, and for this reason, most reputable museums won’t purchase a piece without some degree of documentation.

The speed and volume with which Carroll and the Greens13 collected sounded an alarm – to good and bad actors alike – of a willingness to participate in the gray market, where the legality of goods is questionable enough that accredited institutions dare not tread. Many governments prohibit the unlicensed export of culturally significant items, and UNESCO outlawed the trafficking of cultural property back in the 1970s. But in practice, resources to combat such trafficking are extremely limited. The refusal of wealthy institutions to risk their reputations thwarts illegal practice far more effectively than the laws themselves.

Perhaps the Greens, in their inexperience, did not understand the magnitude of their actions. Perhaps the Greens just didn’t care. Maybe when you believe that human souls are on the line, it’s easy to unshackle yourself from the ethical and legal trade guidelines that shackle secular academics. Maybe the money saved and the ancient items procured were powerful enough to make the risk worthwhile.

Whatever the case, the sudden appearance of a prolific private collector with unlimited funds and a disregard for the rules that tether secular-minded clientele shook the artifact market as a whole. As soon as the search began, Carroll and the Greens found bargain price tags affixed to one-of-a-kind treasures that more fastidious curators deemed suspect. Each new addition further fueled fantasies of a grand establishment capable of redeeming even the most cynical of souls.

The team set on manifesting an unrivaled bible museum went to great, albeit highly unconventional, lengths to procure impressive items to fill future halls. Roberta Mazza has shared a significant amount of evidence suggesting that one artifact, at the very least, came directly from an eBay listing. Carroll found himself deconstructing Egyptian death masks in kitchen sinks in far-fetched hopes that the cartonnage14 itself might have been constructed with papyrus scraps tangentially related to holy scriptures. In their pursuit, they traveled to no less than four continents.

But time and time again, the Middle East called to Green and his partners. It’s only natural. In addition to being the birthplace of humanity’s earliest civilizations, the land where Asia and Africa meet begot all Abrahamic religions. Abraham himself first spoke with God in the bustling metropolis of ancient Ur, located in present-day Iraq. Moses is said to have freed his people from Pharaoh’s bondage by way of the Red Sea. Jesus Christ was crucified in the hills of Jerusalem.

Surely, if the secrets of God’s nature are to be discovered, they’re somewhere in that soil.

It was this mindset that ultimately led David Green’s second-born, Steve, to a hotel conference room in Dubai during the summer of 2010. reen saw promise within the remnants of people long gone, haphazardly arranged on tables and floors. And just like that, the history of the lost city of Irisagrig would forever become inextricably tied to a modern-day evangelical empire.

(CONTINUED IN PART 2)

If you enjoyed this essay and want to say thanks, please consider buying me a coffee 😎

In 1972, the year Green’s frame-making operation grew large enough to warrant leasing a brick-and-mortar outlet, the legal minimum wage in Oklahoma was $1.40. It is difficult to know exactly how much labor went into assembling the frames, but in order to reach the minimum wage threshold, workers would have had to crank out a frame every four minutes – a tall order for anyone, let alone a person with inhibited movement. While this practice was completely legal (current federal law permits employers to pay disabled workers a fraction of minimum wage), it’s certainly a questionable practice coming from a guy whose entire schtick revolves around stewardship.

(One store might only offer yarn, knitting needles, and crochet hooks, another might specialize solely in supplies for ceramics, et cetera…)

For what it’s worth, Forbes gave Green a philanthropy score of 2 (indicating that he has given away 1-4.99% of his total wealth).

Formerly known as Zion Bible College

See: One Hope, YouVersion

The Servant Foundation is also notable for funneling about $65 million to the Alliance Defending Freedom Christian legal advocacy group between 2018-2021. ADL has litigated for policies restricting access to abortion and contraceptives, supporting adoption policies that discriminate against non-Christians, the prevention of decriminalizing homosexuality abroad in countries like Belize, and overturning the Johnson Amendment (which restricts political campaigning by tax-exempt non-profits (i.e. churches)). The Servant Foundation has since renamed itself to The Signatry, probably because backing an organization deemed an extremist hate group by the Southern Poverty Law Center isn’t exactly a great look.

As of 2024, “He Gets Us” is no longer affiliated with the Servant Foundation. A nonprofit called Come Near now manages the religious ad campaign. Mart Green is one of six individuals listed on the organization’s board of directors.

This includes a position on the board of trustees at the Come and See Foundation, responsible for the production of a televised historical drama chronicling the life and times of Jesus Christ titled The Chosen. The next time you walk into a Hobby Lobby, you’ll likely find DVD collections of the series stacked for sale by the register

Incidentally, following Van Kampen’s death in 1999, the collection was transferred to the now-defunct Holy Land Experience in Orlando, Florida. No one seems to be entirely sure where Van Kampen’s collection was physically stored following the 2020 closure of the Christian amusement park, even among relevant scholars of ancient Christianity. Likewise, no catalog detailing the extent or provenance of Van Kampen’s collection seems to exist.

Financially and/or spiritually; with the Greens, it’s all intertwined.

It’s unclear where, exactly, these artifacts are stored. However, the authors of Bible Nation stated the following: “Everyone we have spoken to confirms that the Greens have excellent storage facilities for their artifacts – better, often, than those found at many major universities.”

Shipman, ironically, was pushed out of his own project early on due to ongoing personality clashes described as “awkward, awkward, awkward”. Shipman died of natural causes in 2013.

Cartonnage is similar to papier mache in that it is a flexible material constructed out of plaster and scraps of linen or papyrus. It was common practice to recycle discarded documents and archives to construct funerary materials. The deconstruction of Egyptian cartonnage in hopes of finding biblically relevant materials is objectively deranged. That said, to men like Green and Carroll, the destruction of such relics was justifiable; the possibility of marginally strengthening the veracity of biblical narrative (and, theoretically, sparking a divine relationship with the Almighty) far outweighs the loss of an earthbound culture.